Electronica - the electronic music of Pete Townshend

Pete Townshend is a pioneer of electronic music. His work with synthesisers dates back to 1971, and he has used them to create amazing soundscapes, and to help build a rhythmic frame for some of his most famous compositions. His love of experimenting with forward thinking technologies stems from lessons learned in his days at art school. Pete’s early synthesiser work written for the Lifehouse project and later Who albums was groundbreaking, and the timeless quality of his music continues to excite new fans who recognize the hypnotic arpeggiated electronic effects used in the theme songs to the popular CSI television series. Pete continues to push the technical and creative boundaries of electronic music, using musical technologies extensively as a compositional tool to help build song structures and produce exciting new soundscapes and orchestration.

The following is a close look at Pete’s work in the world of electronica over the years, primarily told in his own words sourced from various interviews, articles, liner notes, diaries, and his autobiography.

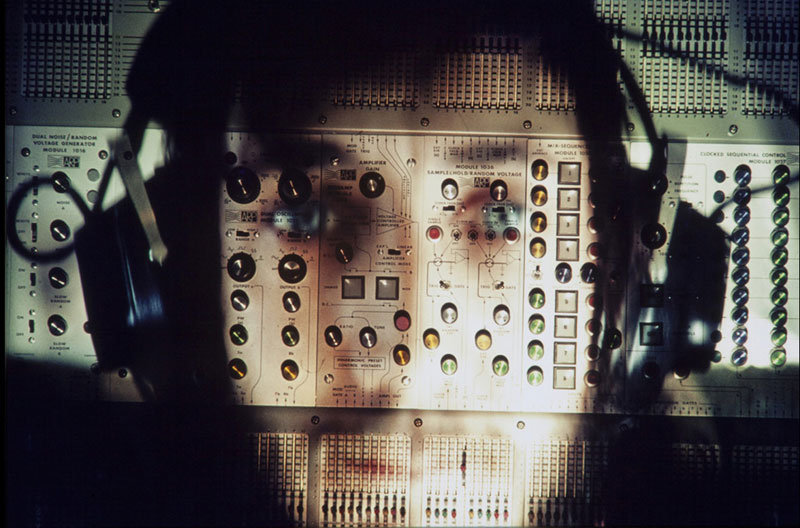

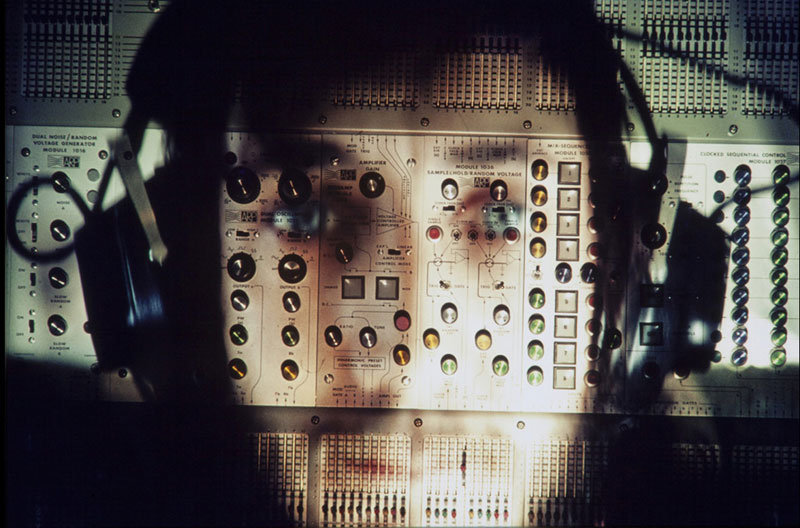

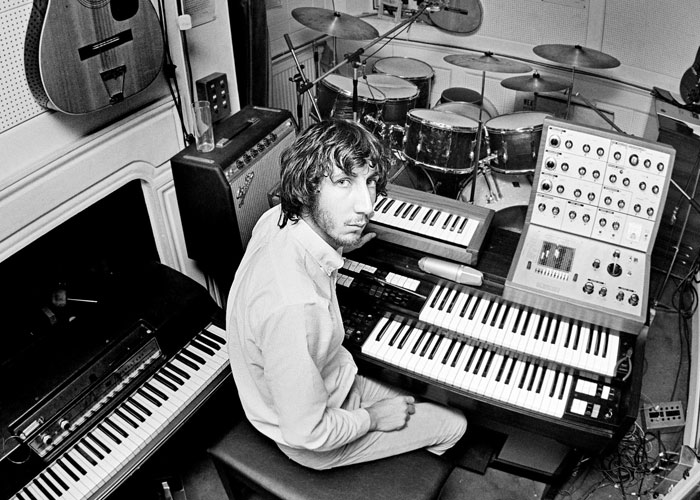

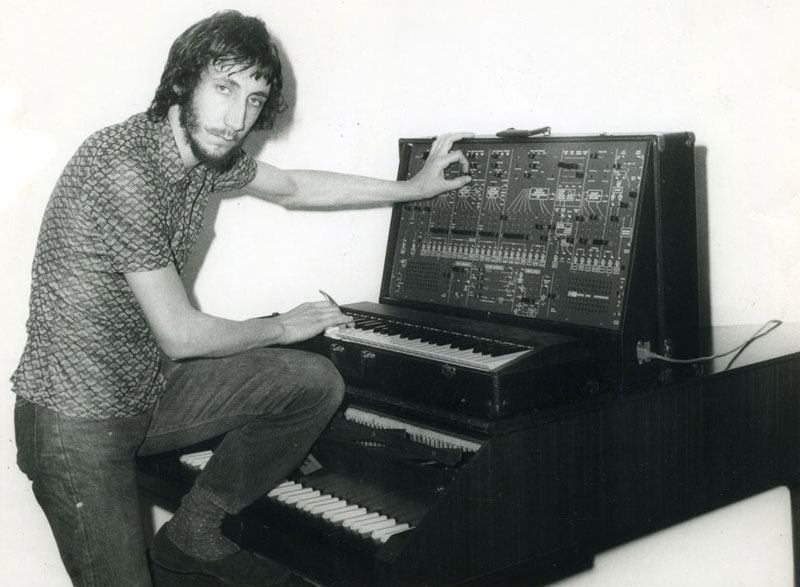

Photo © Pete Townshend with ARP 2500

Photo © Pete Townshend with ARP 2500

Electronica pioneer – Pete’s early influences and experiments

“My forward-looking notions were all implanted in me at Ealing Art College by Roy Ascott and Harold Cohen. They were able to see that computers were coming, and could also see (which is the amazing part) that they would change the way art would work, and language itself. For years I thought nothing about any of this. I had been sidestepped into mysticism and expressed some of that in Tommy. I was also involved in rock marketing and image making. By the time The Who hit 1971, the band was about to turn into a cartoon of itself; Roger dressed as a fringe topped with a curly mop, John using his fingers on the bass as though he was eating crab claws, Keith playing drums with his head on fire, laughing until he cried, me wearing a crown and a tie-dye jump suit, our managers had decided to turn to heavy drugs for amusement. I decided to move aside and back to academia, and art school inspired experimentation with no boundaries. I was getting steeped in extraordinary ideas by people like Tim Souster, Roger Powell, Karlheinz Stockhausen, and others. I was always trying to come up some new way to process sound that would take me away from the traditional processors used in studios. I quickly found that one of the principles of electronic music was its reproduction through reprocessing systems — “myriad” speaker arrays, or swept filters.

"I just let my imagination go crazy, and people like Tim Souster, in particular, just egged me on. I can remember Tim describing aural head implants for the reception of music and information in 1971. I nodded sagely, knowing he was probably right, and of course he could be proved so any second now. He introduced me to the folk at the BBC Radiophonics Workshop and Karlheinz Stockhausen. Roger Powell and I had some incredible brainstorm sessions over nothing more powerful than a cup of tea. On one occasion we invented a contra-rotating magnetic wheel echo device combined with a moving tape loop that would record individual guitar notes and immediately play them back in reverse.

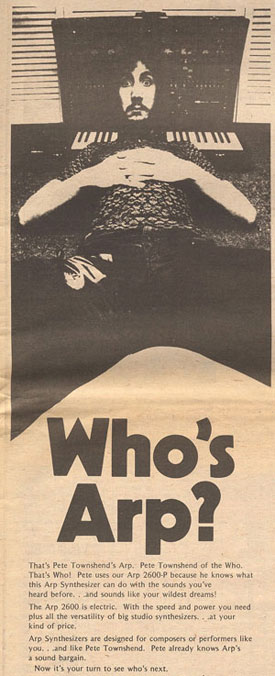

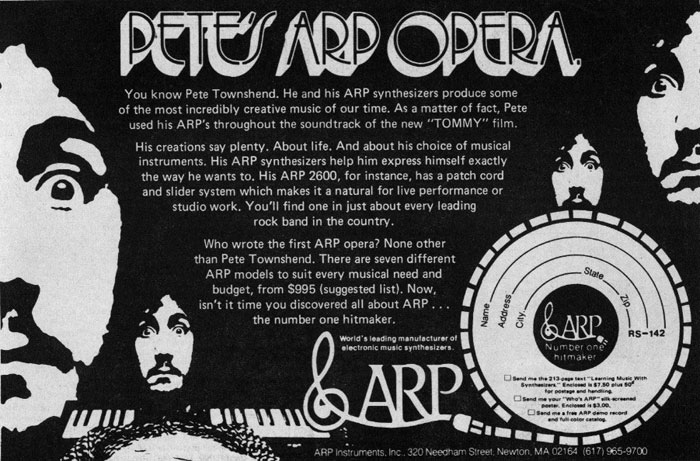

Photo © Pete Townshend with ARP 2600

Photo © Pete Townshend with ARP 2600"What stopped me in my tracks soon after the research and the demo recording was the fact that all these effects were impossible to reproduce live. If I had been able to work live, The Who would have turned into Tonto’s Expanding Head Band. I saw a lecture at Ealing by Malcolm Cecil, one of the founders of Tonto — and he still has the big Moog I think — and he was an incredible inspiration. That would have been in 1963. Kit Lambert had been pretty wacky as our producer as well. During one session with The Who, he ran around the room holding a microphone to generate interesting phasing and ambience. The Beatles had challenged us all I think, to try new things.” [Electronic Musician interview Aug 1, 2007]

“I had given a lecture at Winchester Art College about the use of tape machines by non-musicians. In the audience was Brian Eno, the experimental musician, who cites the lecture as the moment he realized he could make music even though he wasn’t a musician. I wanted to go further. Encouraging our audience to become part of what I did as a composer and songwriter, and to contribute to the sound we produced on stage, was an important part of the second phase of my idea. I believed synthesisers would make it possible for non-musicians to express their creativity, but first I needed to be completely hands-on about them myself, as a layman.” [Who I Am autobiography 2012]

“Fiddling with three makes of Synthesiser and twenty brands of tranquilisers. If nothing else, the past year's preoccupation with electronics has bestowed on me an inate love of wire. The sight of a Moog Synthesiser smothered in patch cables brings me to a state approaching orgasm. A 13 amp plug starts my heart beating faster, and the inside of a television set is enough to reduce me to tears. My latest addiction is chewing solder. What a high man. Really burns me up. Keeps my mind in flux. Never get stoned on a dry joint, chew solder. Yuk.” [The Pete Townshend Page Melody Maker March 13, 1971]

“I envisaged the practical integration of synthesisers into the regular rock-band format. I imagined The Who playing along with rhythmic synthesiser sounds, or pre-prepared backing tracks on tape. By now musicians knew how to overdub in a recording studio, that is, play along with pre-recorded music, but in the live arena drummers were used to defining the tempo and pace of any particular song. In my home studio I played Keith a few synthesiser-chopped rhythmic demo backing tracks. It was a revelation how well and comfortably Keith was able to play along, and I realized this was how he had always played drums with The Who, following, rather than leading, the tempo set by John and myself.” [Who I Am autobiography 2012]

“I definitely want to start using cartridge tapes on stage. You hit a foot button and you get the sound. And also processing the voice through the synthesiser and also settin' up synthesisers to play rhythms. They have these things called sequences on ‘em. You do all the work before the show, you set the thing up then you start it going and play on top of that. Once the group establishes a way of monitoring the effects of the tapes or whatever, we're OK. […] We are electric musicians, after all. The guitar is a stepping off point . . . the guitar has become if you like the violin of rock orchestra. It's the instrument through which identities and personalities are established. You can much more identify a guitarist, even, than a violinist. . . it's become the instrument which is almost like a voice, there are different sort of sounds that are made from different ways of playing and it's like . . . you can recognize guitarists. So there's always that bit of humanness, if you like, but it's only a breaking off point because a guitar is not that much just a guitar, but once it becomes electrified it's turned into a giant instrument which can play to 60,000 people. It can also do a lot of other things, a guitar can be the control center for a synthesiser . A guitar can go into a synthesiser and have it's sound taken apart and put back together again in a different form, so that you're playing the guitar, but the actual sound that comin' out is a completely different thing.” [Crawdaddy interview Dec 5, 1971]

“I’m proud of what I did, but I was hugely supported, and guided. Tim Souster, Roger Powell, Ron Geesin and many others steered me when I started with electronics and rapid tape editing in 1971.” [Off Beat magazine interview Apr 20, 2015]

“I am clearer today about how my songwriting process had evolved by this time [1971], but I had been writing songs professionally for just six years, and was still getting used to the enormous technical jump I’d made during the summer by incorporating a multi-track tape machine into my home studio. Access to my first music synthesiser was important too. What I knew was that once I had a good musical idea I could work much more quickly and efficiently than ever before, and my songwriting could be more ambitious.” [Who I Am autobiography 2012]

Early electronica equipment

Photo: Chris Morphet/Redferns/Getty Pete with the Lowrey Berkshire organ and EMS "Putney" VCS3.

Photo: Chris Morphet/Redferns/Getty Pete with the Lowrey Berkshire organ and EMS "Putney" VCS3.

"I used the Lowrey Berkshire organ many times on Quadrophenia. These organs had more special effects built in than the more usual Hammond." [Quadrophenia – The Directors Cut liner notes 2011]

“I commissioned one of the first small synthesisers from a British company called EMS. Before the machine (the ‘Putney’) was delivered, I was given its manual, which became a vitally important resource. It opened with a simple description of how sound is made, how it travels through the air and how it is reproduced electronically. Clear diagrams made the basic physics behind musical sound easier for me to grasp.” [Who I Am autobiography 2012]

“My father-in-law, the orchestral composer Ted Astley, bought himself an EMS synthesiser (I think he bought two in fact), so I saw quickly how effective synthesis could be utilized to emulate orchestral textures.” [Off Beat magazine interview Apr 20, 2015]

“The first sequencer I worked with was in 1971, the analog one that came with the ARP 2500. Later I tried the digitally clocked sequencer made by EMS in 1973. In fact, the first filtering I did was with the little British EMS synthesiser called the “Putney” VCS3. I persuaded my genius father-in-law, Edwin Astley, to buy a couple, and he became quite adept at using them — great tool for such a gifted orchestral composer.” [Electronic Musician interview Aug 1, 2007]

"To be honest the main leap of understanding for me was the manual rather than the little synth. I suddenly realised what sound actually was, what timbre was, noise, frequency, etc. I still have a VCS3. I met its creator Peter Zinovieff recently and was surprised to hear him call it a ’silly little box’. Despite that I think he has great affection for it, but his dream was always computer music and now we all have that." [Three Questions with Pete Townshend Synth History 2020]

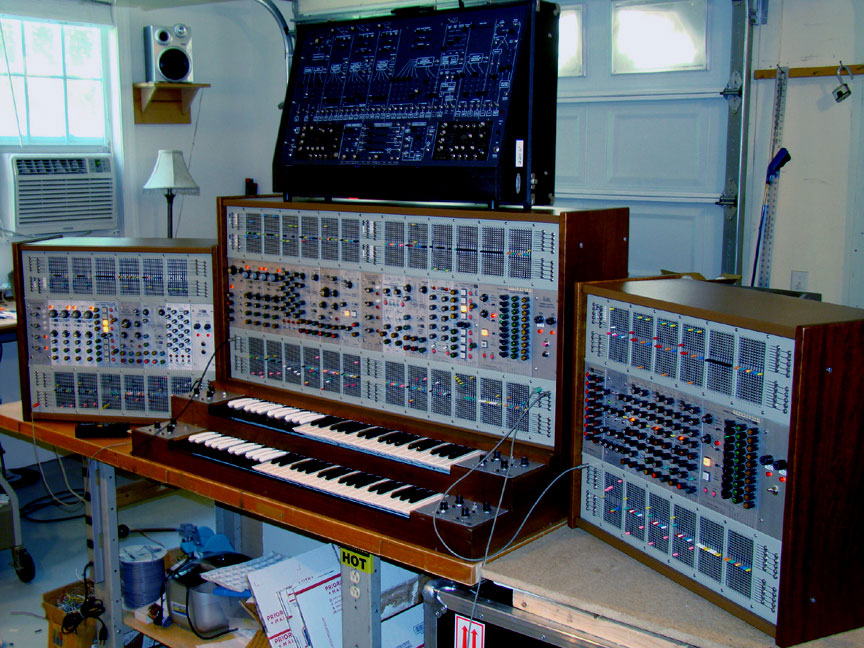

Pete recently hired CMS Technical Service to restore his ARP 2500 / 2600 systems for an upcoming electronic music project he has planned. You can view videos of the tuned up system being played here and here.

Photo: Phil Cirocco of CMS - Pete's fully restored ARP system

Photo: Phil Cirocco of CMS - Pete's fully restored ARP system

First use of synthesisers on Who's Next

“Perhaps unexpectedly for such a huge selling album, Who’s Next has an experimental and revolutionary edge in its use of synthesisers. The VCS3 and ARP synthesisers programmed by Pete weren’t used merely to add superficial gloss to the production but were utilised as a fundamental structure of The Who’s sound. At a time when the synthesiser was still very much a melodic novelty item, Townshend pioneered a cyclic synthesiser rhythm track upon which songs such as ‘Baba O’Riley’ were based. In 1971 this was a radical, indeed, unprecedented breakthrough, with only Stevie Wonder working along the same lines (even so, Wonder’s synthesiser experiments only appeared a year later, 1972). Pre-programmed synthesisers and sequencing are commonplace in pop and dance music nowadays, but Who’s Next, it should be remembered, is where they first appeared on record. As a matter of course, most all synthesiser tracks were recorded at Pete’s home studio and brought to the Who’s sessions as finished products.” [John Atkins from Who’s Next liner notes]

“I had planned to conduct rather simple experiments during these [Lifehouse] concerts producing pieces of music for some loyal audience members. In this experiment my most earnest champion was the late Tim Souster, composer-in-residence at Cambridge University and electronic music performer. He introduced me to Karlheinz Stockhausen and members of the BBC Radiophonics Workshop. I had no hope of producing anything like the expansive music I had envisioned and attempted to describe in my fiction, but certain people around me believed that was my target.” [Lifehouse Chronicles liner notes 1999]

"Tim Souster was helping me with my Lifehouse project. He introduced me to Karlheinz Stockhausen, Delia Derbyshire, Brian Hodgson (BBC Radiophonics Workshop) and helped me see the inevitability of wireless technology." [Three Questions with Pete Townshend Synth History 2020]

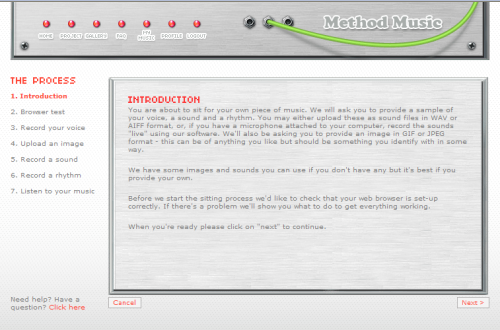

"Baba O'Riley emerged from some experiments I'd been doing with tapes and synthesisers. The idea was to try and translate someone's personal details into music by inputting height, weight and various other information about them, which the synthesiser could then select notes from and turn into musical patterns. This is something that still fascinates me and I'm continuing to explore the possibilities of it with the Method Music software we've developed with mathematician Lawrence Ball and software-engineer Dave Snowdon, which allows a "sitter" to create a unique piece of music from their own personal data." [Song by song commentary AOL Oct 5, 2006]

“I was a big fan of Terry Riley, and in the 70's used Terry Riley and the Indian teacher Meher Baba for one of my first experiments in this particular process. The music that came out of that was called Baba O'Riley, Baba for the Indian teacher and Riley for Terry Riley. Put the two things together and produced a song now which to this day is the one that for some reason, particularly American audiences, go crazy about. But the ripply sound in the background is the characteristic sound that was produced when I started to program and work as a serious electronic music composer.” [Lifehouse Method launch 2007]

Won’t Get Fooled Again: Lowrey Berkshire TB0-1 organ and EMS VCS3 Listen to Pete's demo and alternate Record Plant recording

“We began on the first day with “Won’t Get Fooled Again.” Not a bad way to start. With Pete’s permission, I edited the synthesiser track from his original demo, as it was a little too long, and played it in to the band in the studio. They performed live to it with remarkable skill, the synthesiser dictating a constant tempo for every bar of the song, with them staying locked relentlessly to it throughout. Roger Daltrey’s powerful vocal equaled the energy of the band, capping the whole thing off with that amazing scream just before the end of the song. I have a residing memory of sitting in the truck, my hair being parted by what was coming out of the speakers, a massive amount of adrenaline coursing through my veins. There have been a few occasions over the years when I have been completely blown away, believing without a doubt that what I was listening to would become much more than just commercially successful but also a marker in the evolution of popular music, and this was one of those moments.” [Glyn Johns]

“I used gated Lowrey organ via EMS VCS3 gated filter. No sequencer. I got my ARP 2500 system (huge) just after I’d recorded the first few demos for Who’s Next.”

“Pete is playing block chords spread between the two keyboards of the 1968 Lowrey Berkshire Deluxe TBO-1 organ. The output of the organ is fed into the audio input of the EMS VCS3 mk1 Synth. The first bit of processing to be applied to the organ sound is a low-frequency oscillator (LFO) controlling the frequency of a voltage-controlled filter (VCF), using a sine or triangle wave shape. In other words, the Synth is turning the tone of the organ from mellow to bright, up and down automatically. Step 2 has the output of Step 1 being fed into a voltage-controlled amplifier triggered by a square wave LFO . This means the VCS3 is turning the volume of the organ on and off in a repeating fashion.” [Rich Rowley WBTracks]

An early version recorded at the Record Plant sessions in New York features a different synth pattern that was recorded live in the studio. "No tape was used. What we did was play an organ through a VCS3 live with the session. So we had to keep in time with the square wave, but the shape was moveable. It was an experiment initiated by Roger and was fairly successful." [Who's Next Deluxe Edition liner notes]

Baba O'Riley: Lowrey Berkshire TB0-1 organ Listen to Pete's demo and long instrumental version

"Baba O’Riley was a cheat. I couldn’t get the sequencers and mix-sequencers on the ARP under my fingers fast enough so I emulated sequencing and tape delays using the Marimba Arpeggiator effect on my Lowrey Berkshire. "

“I went out, bought a Lowrey Bershire organ, pushed the marimba button, and played. And people kept saying, ‘That’s incredible synthesiser work on that,’ and I’d say, ‘OK, sure, you’re telling me, right?’” [Musician interview 1982]

"For the Lifehouse series of electronic music experiments which involved trying to use statistical information about people to make random music… you know in this day and age you can go out and buy a $50 computer program to do the job. You put your height and weight and astrological details, the color of your skin and length of your hair, and away you go and you get a piece of music out the back. In those days it was a pretty tough prospect. But I thought I would start with an experiment based on the statistics of my Indian Master at the time, Meher Baba. When I finished I was amazed to hear that the end results sounded very much like a piece by a guy called Terry Riley, who I was very into at the time. So I called it Baba O’Riley. That was it really.

It was a mixture of devices. It was using organs, which were getting pretty fancy then, and synthesisers together, and trying to find ways to synchronize the clocks together. Recording random sections of stuff onto tape, cutting tape up, re-recording bits of tape, cutting the tape up again, and getting rhythms from it. That was really what that was all about. I was really into… you know I had a studio in my house, and I had an 8-track tape machine and a dozen quarter inch machines, and a basement full of weird speakers, and echo units, and chains, and synthesisers, and oscillators, and all that kind of electronic music stuff. But what I was very good at was cutting tape. In those days electronic music was about cutting tape. I could do that and I could do it fast. Baba O’Riley has something like two or three thousand edits in it. The master tape goes by and it’s all white, it’s just sticky plaster from start to finish. What’s really interesting is the stuff that I was cutting out, I was sticking together on a reel to keep it tidy. And that piece is a really interesting piece of music in it’s own right. But what I then did was put a piano over the top, put a guitar, and a vocal, and made it seem more like rock and roll." [In The Studio interview]

Going Mobile: Guitar into ARP 2500 synth envelope follower Listen to Pete's demo

“On the album, on Who's Next, there's a very simple one which we use with the ARP synthesiser called an envelope follower, where you plug the guitar in and you get a sort of fuzzy wah-wah sound. But the guitar itself [on Going Mobile] was controlling the amount of filter sweep. When you hit the note the filter went Bwaaumm! And when the string stopped the filter closed so you got nothing.” [Crawdaddy interview Dec 5, 1971]

Bargain: ARP 2500 Listen to Pete's demo

“At this time I was still coming to grips with the incredibly rich harmonics that my ARP 2500 synthesiser produced, even with a single voice and here one part seemed enough. I still think that Who's Next is one of the best sounding Who albums because the demos for that record were so good. There were good songs, and good ideas, but Glyn Johns our producer stuck his neck out to enhance and evolve not just the songs, but also the sounds I had produced at home.” [Scoop liner notes]

Quadrophenia and ARP synthesisers

“Pete was really big-time into the synthesiser thing. The ARP 2500, which he used exclusively during the Quadrophenia sessions, was a modular synthesiser. He never brought that down to the studio. He kept that at home. You couldn't move that around. You couldn't keep sounds on it. When you got one sound, you'd have to patch everything up. You couldn't click a button and keep it. Then it used to go out of tune all the time, so you'd have to tune up all the oscillators. It was an enormous pain in the ass. You'd spend an hour getting a sound, then you'd play it, and then you'd have to take out all these patch cords and patch up for a different sound. You'd never get the sound exactly the same, even though you took notes. It would never be exactly the same the next time. So it was far from perfect. It was a beast. So Pete would work at night feverishly recording these things on his 16-track. That was mainly because Pete wanted to use the hours and hours and hours of synthesiser stuff that he'd put in on these demos, because there was no way that we could spend as much time as he needed for the synthesiser parts. He used them in more of an orchestral fashion. Beautiful strings and orchestra. When you think of Quadrophenia, you don't think of synthesisers so much. You think of strings and you think of horns. He used synth horns, and of course, Entwistle used his real horns. It was a nice blend, with the both of them. I never recorded any of the Entwistle horns. He did them in his studio. He would take the tapes home at night, and Pete would take the tapes home at night. They'd all record stuff at their own studios. John had his own studio in his house, and he had his own engineer. I don't think I ever met him. Pete did orchestral stuff rather than synth-y stuff. The 2500 ARP synthesiser was really brought in as an answer to the Moog. It was like its competition. It's very cool. It's all big modules with a keyboard in the front. I didn't record one synthesiser part. He did all of it himself, and it was all done before we started. For that matter, all the stuff on the Tommy film too was done at Pete's house. All of the horn parts were done at John's house.” [Quadrophenia engineer Ron Nevison, interviewed for Richie Unterberger’s Won’t Get Fooled Again: The Who From Lifehouse To Quadrophenia book]

“One condition that had to be met before I could launch into tackling the technical demands of Quadrophenia, was that I should have viable technical support. My experience with Lifehouse had been salutary for a number of reasons; not least my inexperience at writing a film script, but the main stumbling block had been the fact that the learning curve on the use of programmed synthesisers and the possibilities of using computers and stage tapes was so steep. I’d achieved plenty but my advisors were friends like Tim Souster (from the BBC), Roger Powell (from ARP systhesisers) and Andy Berazza (from Allan and Heath mixing desk builders), who were not employed by The Who or even contracted as consultants.” [Quadrophenia – The Directors Cut liner notes 2011]

“For Quadrophenia, and the string sounds for the Tommy movie soundtrack that I did straight afterwards, I used a combination of real violin (that I played myself, sometimes set up to open tunings to suit the track) and sounds from a combination of subtractive synth “chains” I set up on my ARP 2500 studio synthesiser. I was able to produce between six to eight of these “chains” at once, each one a single violin emulation. I used keyboard to state the note, but I produced the output by “bowing” one side of a ring modulator using a potentiometer with a knitting needle stuck into the shaft — the other side of the ring-mod of course had the combined six violin sounds passing through it. I probably took down four tracks of that, giving me a section of 24 to 32 “violins”. The real violin simply added “rosin”. I used that trick on a track on the latest Who album Endless Wire — listen to “Two Thousand Years” and you can hear Vienna strings combined with violin, viol and basic cello that I mixed in to create the “rosin”. It sounds hokey, but it’s really fun to do.”

Photo © Pete Townshend PR shot with the ARP 2600 synthesiser used on The Real Me

Photo © Pete Townshend PR shot with the ARP 2600 synthesiser used on The Real Me

Pete discussed his use of synthesisers on the demos he produced for Quadrophenia in the 2011 Quadrophenia Directors Cut liner notes.

The Real Me: “The repetitively random electronic drum rhythm wasn’t particularly innovative for the time, but the American ARP synthesiser featured the ‘sample and hold’ module required to produce it, omitted in the British EMS VCS3 units I had used on the Lifehouse songs for The Who’s Next album written in 1970/1971. I used the same module to produce the irritating electronically modified guitar track on the song ‘Relay’ recorded in March of 1972." Listen to demo

The Real Me: “The repetitively random electronic drum rhythm wasn’t particularly innovative for the time, but the American ARP synthesiser featured the ‘sample and hold’ module required to produce it, omitted in the British EMS VCS3 units I had used on the Lifehouse songs for The Who’s Next album written in 1970/1971. I used the same module to produce the irritating electronically modified guitar track on the song ‘Relay’ recorded in March of 1972." Listen to demo

Quadrophenia: “Then, while I had six free tracks I recorded four synthesised string parts using my ARP 2500 studio synthesiser, employing the bowing simulation device I had invented to allow for tremulando effects, and mixed them down onto the track I’d used for the metronome. I still had six free tracks to use for synthesised horns, again using the ARP 2500 synth, but mixed just four tracks down to one including a pre-recorded drum roll flown in from a separate tape machine. I now had nine performances already, and most of the pseudo-orchestral colour I needed to make the track feel symphonic, and I had used just three tracks.” Listen to demo

Bell Boy: “This demo began entirely as a conventional orchestral arrangement with synthesised bass and horns over which everything was added later. I don’t think I had ever worked this way before apart from my extramural efforts trying to write a proper opera in ‘Rael’, back in 1967. That began on manuscript paper. ‘Bell Boy’ began with a simple bar-count chart that provided a simple guide to the shape of the synthesiser tracks.” Listen to demo

Quadrophenic – Four Faces: “The Lowrey organ I had used often on the songs for Lifehouse was employed again here. It is what gives the chorus of this song its clattering optimistic feeling. I had used the same organ sound on ‘Cut My Hair’, with a stuttering repeat.” Listen to demo

Wizardry: “Recorded in August 1972, this electronica was a piece I was relying on to act as the musical transport conveyance for Jimmy from the frustrations of London to the ebullient, crashing waves of Brighton. Today, this kind of random electronic synthesis might sound hackneyed, you can push a button now on a variety of cheap toy keyboards you can buy, or even on your iPhone, and get a similar sound. In 1972, this piece probably took me several days to set up. I was trying to evoke a feeling of movement, and of pattering rain. The drum part sounds a little like modern Acid House slowed down somewhat (thus meaning it is probably not evocative of Acid House at all, but Jungle or something, and by the time of writing both those styles have probably been nudged aside by new rhythms with ever more inscrutable names. The drum shuffle was added to give the feeling of a train on the tracks carrying Jimmy to the sea.”

“An extended piece of electronic music - some of which was used on Psychoderelict.” [petetownshend.com website]

Electronic music used to produce Tommy film soundtrack

Pete produced the entire groundbreaking soundtrack for Ken Russell’s film production of Tommy in Quintaphonic Sound, primarily with the aid of his ARP 2500 and 2600 synthesisers. He recorded new electronic music based backing tracks for all the songs, including many new songs and verses written for the film to help add dramatic license, and also created the various sound effects throughout the movie. The result was a technically stunning cinematic experience for the time, and Pete received an Oscar nomination for Best Original Song Score or Adaptation Score.

"First of all, I don't know how to write tor a real orchestra. It's easier for me to simply sit down with my synthesisers and create the sounds directly, right on the spot. And somehow the results are better, anyway. I can get a precise, tight arrangement with perfect balance and intonation. The synthesiser was used for all kinds of things; the planes flying at the beginning, the explosions, even Oliver Reed singing." [New York City press conference for film opening 1975]

More early synth work on Who tracks

Relay: ARP 2600 - listen to Pete's demo

"Pete's guitar is being processed through an ARP 2600 synth. The guitar output is fed into the audio input of the voltage controlled filter (VCF) section of the synth. Using the sample-and-hold function, the output is connected to the VCF, which automatically turns the frequency (tone) of the filter to different, random positions in a rhythmic style creating the effect we hear on Relay." [Rich Rowley WBTracks]

Join Together: ARP 2500/2600 and Lowrey Berkshire TBO-1 - listen to Pete's demo

"The Jew's harp on the intro is an ARP Synth. It sounds like a four or eight bar loop that Pete built the rest of the song on. The organ part that comes in two bars before the vocals is interesting as it's the same setting as Baba O' Riley, only set to a much slower speed. The organ is also fed through a low-pass filter, which can be heard on the demo." [Rich Rowley WBTracks]

Who Are You: ARP 2600 - listen to Pete's demo and isolated synth track

“I still had the full-size barn studio that I built for mixing Quadrophenia and, while working on the demo for this track, nearly blew my own brains out developing the backing track for the song. The weird background guitar sound on this was created with a top-secret ARP 2600 patch I invented, but the sawing guitar sound at its heart was generated with an ‘E-Bow.’”

“An overdriven ARP 2500 or ARP 2600 synth. The overdriven guitar is fed into a voltage-controlled filter (VCF), which is being controlled by a low-frequency oscillator (LFO) triangle wave. The LFO is set to the tempo of the song at eight pulses per bar, making the tone of the VCF rapidly rise and fall in time with the song. The next step is to make each pulse from the LFO to trigger sound alternately from the left and right sides of the stereo picture.” [Rich Rowley WBTracks]

Sister Disco: ARP 2500 - listen to Pete's demo

"For this track I spent a lot of hours programming my analogue sequencers in my ARP 2500 studio synthesiser. It isn't quite KRAFTWERK, but in 1976 I don't think they were doing much better. This is a perfect example of the progression I was making towards theatrical music writing. I was trying to evoke absurd Baron Munchausen musical textures. Roger sounds so seriously intent about everything that the pomposity becomes real and threatening rather than pictorial."

“I used my huge ARP synthesiser’s sequencer to create a set of pre-written arpeggios that I could trigger by pressing buttons. The effort that went into it was out of all proportion to the end result. Our keyboard player – newly hired at the time – Rabbit, complained that he couldn’t work out how I’d played it, and was relieved to hear I’d done it with a mini-computer.” [The Who Jukebox liner notes]

New Song: ARP Omni - listen to Pete's demo

"New Song' was the first song I ever wrote on a polyphonic synthesiser. It was blocked out on an ARP OMNI, that company's first polyphonic machine. It may have been the first multi-voice synth ever. But I cheated quite a lot; it had only one filter and envelope-shaping amplifier."

Love Is Coming Down: ARP 2500 - listen to Pete's demo

“One trick I used during the Who Are You album (the demo of Love Is Coming Down), based on the same thinking, was to modulate a polyphonic ARP string machine using the sound of a real violin through a vocoder. The sound of the real violin was the ‘voice’ that modulated the string pad. It sounded awful, until you combined it with a pad of untreated synthesized strings — then it seemed to add splashes of harmonics and colour to the synth pad that made it sound, if not exactly real, more like a human sound than a synthetic one.”

You Better You Bet: Yamaha E70 organ - listen to Pete's demo

Eminence Front: Yamaha E70 organ - listen to isolated synth track

"Both of these songs use the same setting, called “Auto Arpeggio.” When chords are held on the lower keyboard, it automatically plays the notes of the chord up, down, up and down, random, etc." [Rich Rowley WBTracks]

"Eminence Front was written around a chord progression I discovered on my faithful Yamaha E70 organ. This organ is almost a synthesiser rather than an organ, using entirely analogue synthesis chips to create its unique sound."

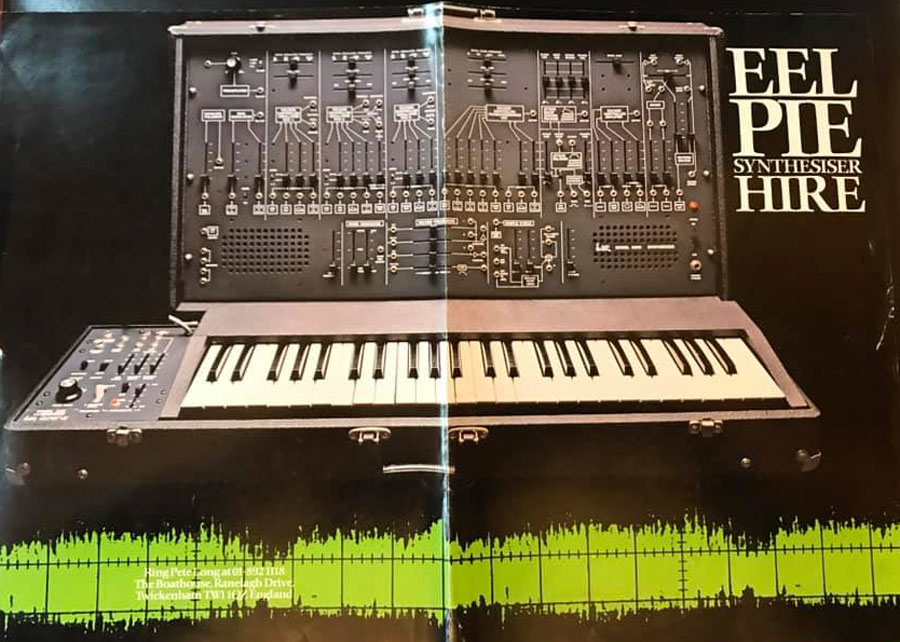

Brochure for Pete's Eel Pie synthesiser hire

Brochure for Pete's Eel Pie synthesiser hire

Composing with synths, samplers and sequencers

"Since 1972 I have used sequencers, arpeggiators and computer based random music generators as a part of my composing process. Tied to the guitar or piano, I write conventional songs, and I have been using the same chords for many years - unable to break free because of a lack of complete musical prowess at a classical or jazz level. In this respect I’m like many people. A lot of my music is what a poet might call ‘found’." [Korg ProView Magazine]

"The music computer had landed in two forms. There was the Fairlight CMI, a synthesiser/sampler workstation beloved of New Romantic bands; by the time I started work on White City I had bought my own. The other system was the Synclavier, a digital FM synthesiser with a microprocessor-controlled sequencer. I realized these developments meant I would soon be able to compose and orchestrate very seriously, without the expense of using real orchestras or the barrier of working with orchestrators like Raphael Rudd or Edwin Astley." [Who I Am autobiography 2012]

"I actually favour organs based partly on synthesiser technology, and synths that are most like organs. So keyboards. Although I do work on electronic ambient music, Beats and chaos, I am principally a songwriter, so I like inspiration to emerge from what I put in front of me. (That said I can build sounds from the ground up, I’m not bad at some coding or object-based computer music like REAKTOR and MAX. My brain is still pretty keen.)" [Three Questions with Pete Townshend Synth History 2020]

Pete demonstrates his compositional process and use of synthesisers in a Southbank documentary in 1985.

“Years ago I learned to write some code (for the Fairlight CMI) and later wrote Hypercard code for my little Mac computer. I’m not great at code, but if you do even a little you quickly see how amazing it is that skilled coders are able to do almost anything one can imagine. I love the concept of “The Internet of Things.” I can see now how music–visual–installations could be controlled and modified from anywhere in the world. I’ll be able to tour from my bed. So expect more interference….” [Off Beat magazine interview Apr 20, 2015]

“The Mellotron, which used a form of analogue sampling, had been employed by The Beatles and Bee Gees back in the mid-Sixties. Digital sampling had been pioneered by Fairlight, and by Ray Kurzweil, who reserved his first invention for Stevie Wonder. Once I got my hands on a Synclavier, though, I saw that the composer, already king, would become omnipotent, freed from working with session musicians and arrangers and producers for hire. And as soon as the technology arrived to offer the compression of digitial music, it could be transmitted down a telephone cable, and artists like me wouldn’t even need record companies." [Who I Am autobiography 2012]

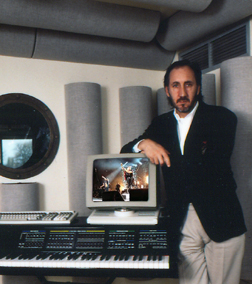

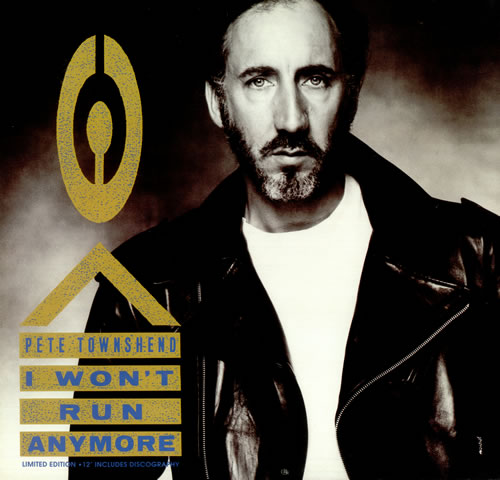

Pete with Synclavier

Pete with Synclavier“[My demoing process] has gotten much more sophisticated because I’m using the Synclavier, so my original Portastudio four-track demos are now actually done on a four-track direct-to-disc system which costs more than my house, literally. It mean that odd little moments on Iron Man, like the vocals and basic accompaniment on “A Fool Says,” are knocked out very, very loosely. I tried redoing it, and I just thought, “Well, why” It’s all there.” So my demo process has changed only in terms of the more modern equipment, but that’s enabled me to work on a much more sophisticated level, more like a composer than a songwriter. Now, I don’t need the structure of a song before I start to work on it. Working on a Synclavier or on MIDI software or whatever it is that I happen to be using, I can actually approach a shape with a phrase, a musical phrase, and start to develop that. And I can actually try other intellectual ways of approaching a piece of music. … I mean, Tommy would have been so much better if I had had modern equipment. It would have been much, much, much easier.” [Guitar Player Sept 1989]

“The Synclavier is a right hand brain machine, it is part of the creative process. A computer is a left hand brain machine. When I am composing I want to stay in the right hand brain side, when I use a computer I have to keep switching between the two sides".

"I like synthesisers because they bring into my hands things that aren't in my hands: the sound of an orchestra, French horns, strings. There are gadgets on synthesisers that enable one to become a virtuoso on the keyboard. You can play something slowly and you press a switch and it plays it back at double speed. Whereas on the guitar you're stuck with as fast as you can play and I don't play fast, I just play hard. So when it goes to playing something fast I go to the synth."

“Creating sequenced arpeggiations should not require ingenuity. This is “found” music, like the individual elements in collages in art. One presses some keys, or fiddles around with some software or some setting on a Casio toy, and if what you hear is inspiring, fun, or interesting, you can move ahead with it. It’s what you do with it that counts. The problem with soft synths is never their sound — they often offer superior sound to the originals and terrific extras. But the human interface becomes one you have to construct yourself. For example, the [Arturia] CS80 emulation I use is amazing. But what made the CS80 so incredible was its polyphonic aftertouch pressure keyboard that could be set to change timbre, vibrato, and even pitch both on attack and after-pressure. Each note in a chord could be made to rise or fall in level, or swell with a change in timbre. Just holding a pad could be made interesting and evolving simply by adding pressure to individual keys after you keyed and held the chord. It is almost impossible to set up a good MIDI keyboard now with polyphonic aftertouch. The CS80 also had a great ribbon controller that could be set up to do all kinds of things. That is what gives Stevie Wonder his sound: the aftertouch on his big Yamaha GS1 organ — or me on my Yamaha E70 home organ — again, with polyphonic aftertouch on some sounds. The CS80 and the E70 were based on the GS1 experiment. The only keyboards I have that offer this now are my two Synclavier keyboards and one Kurzweil MIDIboard. Both are really tricky to set up. They are also huge and heavy, especially the Synclavier. Mind you, a used CS80 weighs about as much as a man. Imagine being as inspired as Stevie Wonder and being placed in front of a three keyboard and bass pedal synthesiser pretending to be a home organ, with swell pedals, knee pedals, poly-pressure, great FM string sounds and all. I dream of my own “Cyber-Organ” that once I start to play joins in with me, it has dozens of keyboards like a proper Bach organ, foot pedals, integrated syncopated arpeggiation and echo, a huge “myriad” speaker array with each sound with its own output channel and patch in audio space. I spoke to Roger Linn the other day, and although he has different ideas, we both agree that the stripped-down MIDI keyboard is a limiting interface for music. He speaks of all kinds of new and exciting interfaces.” [Electronic Musician interview Aug 1, 2007]

“Finally, I think it’s really worth saying again, that although I like working analog, I think in some ways I’m just following a current trend, because lots of young musicians I come across seem to want to work that way too. I really believe that great new music comes from pushing at the envelope of creativity, trying new gadgets, new methods, new ways of doing the same old things. As a composer I think Ableton Live has to be the software that has given me the most immediate way to write new things on a computer, rather than tape. At the same time it allows several additional levels of creativity, including that suggestion of mine that “finding” great sounds and loops can inspire new tracks.” [Electronic Musician interview Aug 1, 2007]

Inspirational electronic music gear - the tools of the trade

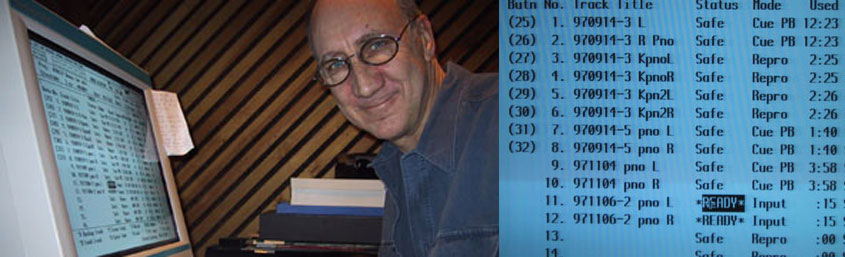

“Since the late 1980s Townshend has predominantly used Synclavier Digital Audio systems for keyboard composition, particularly solo albums and projects. He currently owns three systems, one large Synclavier 9600 Tapeless Studio system, originally installed in his riverside Oceanic Studio, later transferred to a sea going barge moored alongside the studio on the River Thames, and currently based in his home studio. He also uses a special adapted smaller Synclavier 3200 system which can be transported, enabling him to carry on working away from his main studio. This 3200 system was modified to be of similar specification to the 9600, including the addition internally of FM voices, stereo Poly voices and with the large VPK keyboard. This is the only Synclavier 3200 system of this specification in existence, custom designed and built for Townshend by Steve Hills. The third system Townshend owns is one of the first Synclavier II systems ever built. The ORK (original smaller) keyboard of which is on display in his company's head office alongside a pink Vespa scooter.” [Liquisearch.com article on Pete’s Musical Equipment]

“Since the late 1980s Townshend has predominantly used Synclavier Digital Audio systems for keyboard composition, particularly solo albums and projects. He currently owns three systems, one large Synclavier 9600 Tapeless Studio system, originally installed in his riverside Oceanic Studio, later transferred to a sea going barge moored alongside the studio on the River Thames, and currently based in his home studio. He also uses a special adapted smaller Synclavier 3200 system which can be transported, enabling him to carry on working away from his main studio. This 3200 system was modified to be of similar specification to the 9600, including the addition internally of FM voices, stereo Poly voices and with the large VPK keyboard. This is the only Synclavier 3200 system of this specification in existence, custom designed and built for Townshend by Steve Hills. The third system Townshend owns is one of the first Synclavier II systems ever built. The ORK (original smaller) keyboard of which is on display in his company's head office alongside a pink Vespa scooter.” [Liquisearch.com article on Pete’s Musical Equipment]

“I built myself a retro room. Outside my studio, which is a state-of-the-art type place near the river with a Neve, [N.E.D.] Synclavier, and all that kind of thing. I had an old barge that I built in the 70’s to record on the French canals, but I never finished it. I decided to use that barge as the site for my own room. It’s not very big, but it felt right. I found an old, dreadful Neve desk that I can work by memory. I put my old organs in there. I buy an organ every ten years, so there’s a group of organs, my old Yamaha CS-80, and my big synthesiser – the ARP 2500. I bought some new stuff – a Kurzweil K2000, which is fabulous. I think that gathering that equipment together really helped me. This is not a worship of the old, because at the heart of the thing I was going to a Mitsubishi digital tape machine. I was using the Synclavier all the time, which I still embrace every time I walk in the studio despite the fact that the company has gone down. I thank God for these things. It means you can work without fucking musicians. Go buy a fucking Kurzweil K2000, man! It fucking works! You’ve got a SCSI on it, you can put the shit in it, your whole life can be in there. Believe in this stuff. Don’t go back to where I was when I was a kid, fucking dreaming about it and thinking, “If only I had this stuff, how quickly I could grow,” and “How long do I have to wait?” Thank God it happened in my lifetime because I had to wait such a long time. I was making records with echo, bits of spring, and two old tape machines. It’s great to work at home. What’s great is to have time, stuff that works, stuff that you can afford. We’re so lucky now as musicians.” [Keyboard interview 1993]

“I mix old and new. I have pro analogue tape machines running alongside a computer running Digital Performer or Ableton Live. Things have got better. The emergence of digital was tricky. The sound was poor at first. I was lucky because I used Synclavier as my digital medium. That was sampling at 100KHz in mono and 50KHz in stereo back in 1984, with fabulous integrity. Now a laptop can deliver that if you wish.” [Premier Guitar interview March 11, 2010]

Pete at his Yamaha E70 organ on the Sunday Morning TV show October 2012

Pete at his Yamaha E70 organ on the Sunday Morning TV show October 2012

“I bought a Synclavier and was one of the first people in the world to embrace hard-disk recording. Of course I predicted the internet (the GRID) in 1971 in Lifehouse, and music downloading in 1985 in a lecture at the Royal College of Art in London. This is not quite so clever as it seems when you realize that in 1961 my teachers at Ealing Art School were already talking about how computers would change the language and tools of art.” [Pete’s diary Nov 23, 2006 French Grasshopper – 6]

“First picture is me at my Synclavier computer, editing on hard disk. Nothing clever about that in this day and age until you realise the machine in front of me was delivered in 1985. The second picture is of the archaic screen of the hard disk front end. It now has prettier software floating above it that looks more like the kind of stuff you get on modern music computers, but I kind of like it. It looks MIT, Radiophonics Workshop - it looks DULL. SERIOUS. MILITARY. INDUSTRIAL. And thus feels like proper tools for art. ” [Pete’s diary Jan 27, 2001 Sharply focused and dizzy mp3]

“Today I love how broad the spectrum of electronic music is, so much that is now software I used to dream about—I still have my old gear, and I love it, but I also love KYMA, MAX, REAKTOR and other software synth and sound manipulators.” [Off Beat magazine interview Apr 20, 2015]

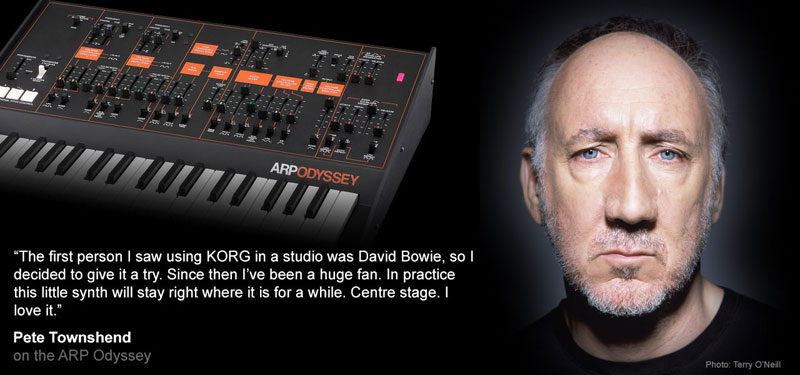

“The ARP Odyssey is very, very close in sound to the original. I was surprised that it is a smaller scale. But it has MIDI IN so a larger keyboard can be used. Needless to say, like the big KORG keyboards, and the MS20 revival (which is also smaller scale), this is a fabulous instrument – and like the MS20 almost an educational tool for newbie synthesists. You can see the sound and controller pathways clearly, and learn what each does. The best thing for me are the modern fader controllers that are so smooth. Making very fine adjustments is easy – that's where this shines. I have only really started to use KORG instruments since the OASYS was introduced. I skipped the Triton. The first person I saw using KORG in a studio was David Bowie, so I decided to give it a try. Since then I've been a huge fan. I think the entire KORG range offers great sound, but also lots of fun especially in the smaller instruments, and the ODYSSEY is so much fun to use, and of course to play with. A child could make sounds come out of it. But when you want to get serious this takes one back to the early days of hard-wired synths and with Duo-Voices is especially great for voices set up in 4ths or 5ths. One advantage of the slighter smaller size compared with the original is that it takes up less room in my cramped control room, and most studios have a large MIDI keyboard. In practice this little synth will stay right where it is for a while. Centre stage. I love it. “ [Korg website Apr 3, 2015]

“I love some of the computer software that comes with the MIDI and Pro Tools world. The Ivory piano module is genius. Ableton Live is beyond criticism, and just gets better and better (and thus harder to use, but it’s still intuitive). Vienna’s orchestral samples, now available with their own sample player, are just superb. I was brought up with the big Synclavier library — Denny Jaeger and so on — and the Synclavier processed each sample in its own DAC line, so there was great integrity to the sounds even though the sequencer quickly got left behind when [MOTU’s] Performer came along for the little weensy Mac. The Vienna samples on a Mac sound as good as those early Synclavier sounds to me (I use MOTU 192HD units in my home studio, not Pro Tools). I love the UAD plug-ins, McDSP — so much great stuff! My favorite sequencer is Digital Performer.” [Electronic Musician interview Aug 1, 2007]

“The AKAI Pro APC40 is an incredibly powerful interface for LIVE. LIVE is already an extraordinary composing tool, with big real-time capability that I have never thought I could ever use. I always thought LIVE would be great for deejays and veejays, but they'd need to be masters of MIDI-mapping to be able to make LIVE really fly the way it can when you have the software under your mouse. But the APC40 makes creating loops and rhythmic scenes, constantly changing and elaborating, so easy. It is intuitive, and everything is right under the fingers. This is going to change Live music based on loops and sample - and of course now LIVE itself is a fully functioning sequencer recording audio as well as MIDI and triggered loops, musicians are going to be able to model sound in the studio to perfection, but then bring exactly the same loops and tracks to life on stage in complete synchronicity with the band - but most important the mood and vibe of the audience. Astonishing. This simple interface has created the most powerful new tool for the stage and studio that I have seen in the last ten years. Deejays are going to go nuts for this – but musicians too, possibly even drummers. Everything is under the fingers. I will go further. This interface, loaded with drum loops makes you feel like that kid in Santana playing for Carlos Santana at Woodstock in 1969. It's a revolution, but this time the only drug is the APC40 . I am hooked. " [AKAI Professional website]

“The AKAI Pro APC40 is an incredibly powerful interface for LIVE. LIVE is already an extraordinary composing tool, with big real-time capability that I have never thought I could ever use. I always thought LIVE would be great for deejays and veejays, but they'd need to be masters of MIDI-mapping to be able to make LIVE really fly the way it can when you have the software under your mouse. But the APC40 makes creating loops and rhythmic scenes, constantly changing and elaborating, so easy. It is intuitive, and everything is right under the fingers. This is going to change Live music based on loops and sample - and of course now LIVE itself is a fully functioning sequencer recording audio as well as MIDI and triggered loops, musicians are going to be able to model sound in the studio to perfection, but then bring exactly the same loops and tracks to life on stage in complete synchronicity with the band - but most important the mood and vibe of the audience. Astonishing. This simple interface has created the most powerful new tool for the stage and studio that I have seen in the last ten years. Deejays are going to go nuts for this – but musicians too, possibly even drummers. Everything is under the fingers. I will go further. This interface, loaded with drum loops makes you feel like that kid in Santana playing for Carlos Santana at Woodstock in 1969. It's a revolution, but this time the only drug is the APC40 . I am hooked. " [AKAI Professional website]

"I don’t use the Korg Karma as workstation. I am interested in it purely as an inspirational tool. I heard about it in magazines and then from my friend James Asher (drummer on some tracks on my first solo abum EMPTY GLASS). I knew from various classical organ scholars I know that the sounds on the Korg Triton were superb, so I decided to take a chance and buy the instrument. I have not been disappointed. The Karma has already allowed me to ‘find’ a whole range of compositions that I would never have worked on without the machine. It reminds me of the Yamaha E70 organ arpeggiation system combined with great Kurzweil quality synthesiser sounds all run from an engine like ‘M’ or ‘Jam Factory’ from the halcyon days of computer music generation. Only it is better. Much, much better. If this kind of instrument had been around in the 60s I would have found my lack of musical ability no problem at all. I would therefore not have needed to become the ‘Performance Artist’ I became when I smashed guitars. This instrument took someone a long, long time to put together. It ain’t quite the Well Tempered Clavier, but it is a definite step towards taking the old beast into a new world. It is, to be frank, one of the greatest new truly playable keyboards to emerge since the Prophet 10 and Yamaha CS80." [Korg ProView Magazine]

"The 1980 Yamaha E70 organ is my top pick. This is based on the PULSE-ANOLOG-SYNTHESISER-SYSTEM used in the GX1. Beautiful, sonorous sounds. Half of the E70 is organ, the other half is synthesiser. Downside? It weighs more than a Hammond. Second is Prophet 10. I still have one, just restored by the Wine Country company in California. With both foot pedals installed (both on filters or other controls rather than just volume) these things are really expressive. They are also entirely analogue, with some digital control. Third is Synclavier 9600. This is out of the reach of pretty much everyone today. Benny Anderson still uses his every day I understand. The technology is cumbersome, but the combination of sampling, FM synthesis and multitrack hard-disk recording challenged the imagination. Again, I still have one, maintained by Steve Hills at 500 Sound in the UK. It’s expensive to keep going, but I feel a duty to it. The keyboard sequencer interface does bypass the computer, so you can just sit at it and play it like an organ if you like. I have Moog, ARPs, Korgs and Rolands old and new. I am also into “boxes”. I love all the new battery powered gadgets, but if I’m completely honest without Cuckoo I wouldn’t be able to operate any of them.

If I were to buy new today, with less cash in my pocket, I’d pick the following: Toontracks EZ Drummer and EZ keys. These are software of course, but so easy to use, and to create even complex musical forms. I used EZ Keys to create the jazzy chords for I’ll Be Back on the new Who album. Made it all up as I went along. The chords were so tricky I had to write them out in notation, and even then had to record the acoustic guitar in short chunks. AKAI MPC LIVE. I love it that this is battery-powered. I used it to create rhythm tracks (that were replaced by real drums) on the latest Who album. I’m not great at finger-drumming, and I think since Dr Dre unquantized everything there isn’t much left to discover, but I like trying! I used to be quite a decent drummer, but not so much any more. Of course MPCs (and Macshine) do far more than finger-drumming these days. NEXUS. This company can be a bit of a shambles sometimes, but whenever I open up this module I get inspiration. It’s genius. The new update is impressive and at last works in 64 BIT. All this stuff is available today, even though OP-1s are sometimes thin on the ground they have just made another batch I believe." [Three Questions with Pete Townshend Synth History 2020]

Electronica work on Pete's solo albums

Pete used the Synclavier, Prophet, Yamaha CS80, and a variety of other synthesisers, organs and drum machines extensively in his solo work in the 80’s and 90’s, including many of the demos featured on his Scoop albums or released on his website.

“On my solo records there are sequences on “Let My Love Open The Door,” “A Little Is Enough,” “Uniforms,” and several others. Often on my solo records the demos became the finished tracks.” [Electronic Musician interview Aug 1, 2007]

Listen to Let My Love Open The Door (E Cola Mix Long Version)

![]()

Tough Boys: "I recorded this onto a half-inch analogue 8-track Tascam tape machine in 1979. I had no proper studio at home in London anymore and had put together a temporary and transportable rig around this machine. Great sounding machine usually, but in this case I was simply chucking down a very quick demo of a strange sound I'd managed to cook up by combining a Roland guitar synthesiser (which was polyphonic) with an ARP Avatar (which was monophonic). I used the ARP on just the lowest string of my guitar, creating a rather erratic bass line. The chord sustain noise is from the Roland, and you can also hear the strings being strummed from a mike I put near them. In the studio (Wessex) when I recorded the track properly I fed each output of the two synthesiser into a separate amplifier, creating a monstrous and wobbly wall of sound." [Scoop 3 liner notes] Listen to Tough Boys

Rat Run: “This dates from the first years of the Yamaha CS80 synthesiser, an extraordinary machine I started to use way back in 1980 sometime. I expect this track was recorded around then. It seems to be the basic chord structure for a song called Man Watching that was the b-side of my solo single FACE DANCES I think. It was a little game I played on my Yamaha CS80 polyphonic keyboard when I first got it in 1977 or 78. I ran a dopey drum box, and just grooved along. We used it as the music you heard when you called my office - for quite a long time.” [petetownshend.com website]

How Can You Do It Alone: "It began with a Yamaha E70 organ backing track which I recorded through eight separate outputs and then re-routed through various echo delays, dubbing in Reggae style. It is that process that creates the bubbling sound, but also all the interesting percussion 'scattering' sounds over the real drums which were added by Kenney Jones at AIR studios in London one night. The strange bass lilt was created by using the organ's internal drum-box on some quite conventional latin setting, but starting the bar halfway through. The organ track was made at my largest studio, Oceanic in Twickenham." [Scoop 3 liner notes] Listen to How Can You Do It Alone

Prelude, The Right To Write: “In early 1983 I was desperately attempting to come up with a concept for the projected Who album that year. While I settled my mind, I did some inventing. I organized a synthesiser whose sixteen unison ‘string’ voices were reproduced through what I called a ‘Myriad speaker system’. This was simply sixteen separate small speakers on mike stands at about head height, distributed around the recording studio in formal string section grouping. As soon as I played a note I knew I’d hit on something. The synthetic string sound was rich and spacious. I recorded it in real stereo with the natural ambience of the room.” [Another Scoop liner notes] Listen to Prelude, The Right To Write

Initial Machine Experiments: “This piece was played on my Yamaha CS80 synthesiser to test a TEAC half inch eight track machine. This is very much indicative of the kind of meandering I get into when locked away with a synthesiser. Someone once said that when you play around with a synthesiser you end up suffering from a disease called 'synthesiseritis'. I suffer happily." [Scoop 3 liner notes]

Elephants: "This was taken directly to a Tascam cassette portastudio. August 1984. It is a really good example of the fiery and bizarre Hammond-like sounds you can get out of synthesisers if you (like me) know what you're doing. The keyboard here was the incredible Prophet 10, introduced some time in 1977 I think. Essentially two Prophet 5 keyboards ganged together, the double layer of related sounds created the most extraordinary movement and harmonic complexity. It you are a keyboard player and you see one of these for sale at under $5,000-buy it. It will take you to a piece of heaven reserved for Hammond players who have taken too much acid. It is also very easy to programme your own sounds. The 10 had a simple step sequencer built into the lower keyboard. It is the sequencer creating the relentless blues pattern over which I played some stock Ray Charles organ tricks. You can read some details about the Prophet 10 on www.synthmuseum.com." [Scoop 3 liner notes] Listen to Elephants

Man And Machines: "The track was constructed entirely on a 'small' Synclavier I used in my home studio in 1985. There are no real instruments at all. I did the drum programming using a tiny Apple Mac running a programme called UPBEAT I loved that little programme. It looked like a toy, but it was very powerful because it allowed many levels of random variation in feel, dynamic and tone. It was driving a Roland MT32 MIDI voice pack. The drums are only available as a single layer, but as you can hear, they make a good noise. The percussion solo was a series of about 40 two bar patterns set to vary in the most extreme way the software allowed. The use of sound effects over strings at the beginning is one of the most beautiful sounds I have ever made I think. It seems to evoke a distant blacksmith's forge or something: a summer evening; buzzing insects; calm." [Scoop 3 liner notes] Listen to Man And Machines

Ask Yourself: “One of the first things I did on my new Synclavier at this time was conduct a series of exercises round the 'Siege' canon I composed on sheet music the year before while I was working on the demos for White City. I had hoped to complete a symphonic piece based on the canon, but really such a task was - and still is - out of my scope. But I produced a large number of simple variations. One of the most harmonically satisfying for me is the one that serves as the middle eight for Ask Yourself which appears on Another Scoop." [Scoop 3 liner notes]

Theme 017: "Another variation on the Siege canon. The notes in my log for this say; SIEGE written variation in Eb. Chart 'Theme 014'. (B substituted for Bb in opening chords for some reason). Trombones, then oboe/flute/pipes take up a folk refrain over lush strings. This was recorded entirely within the Synclavier sequencer with a mixture of sampled and FM voices. ” [Scoop 3 liner notes] Listen to Theme 017

Crashing By Design: “This is my home demo of the track that eventually appeared on my solo album WHITE CITY. I think the drum track is built up in a LinnDrum machine. I got my first Fairlight music computer around this time, and I loved it. I was crazy for it. But the LinnDrum machine, the first one to use real drum sound samples, was a true breakthrough for composers working in small home studios like mine.” [petetownshend.com website] Listen to Crashing By Design

Theme 015: "This 'variation in G' was composed sometime before I logged this take (with about 30 others) on 1 June 1987, therefore it was probably recorded in March of '87. I had recently taken delivery of a large Synclavier synthesiser. The harmonica sound is actually produced on the FM side of the Synclavier. ” [Scoop 3 liner notes] Listen to Theme 015

Iron Man Recitative: “This was recorded around October 1993 on the studio Synclavier I still use for the majority of my composing work. With a few tricks one can record a MIDI keyboard track and live vocal tracks at the same time. I could work in short sections and then edit them together later on. (This is something modern sequencing software manages easily today). ” [Scoop 3 liner notes] Listen to Iron Man Recitative

Meher Baba M3, M4, M5, Baba O’Riley demo: Pete included 1971 ARP synthesiser demos from Lifehouse, which he reworked for Psychoderelict and used as the background to his Gridlife storyline.

Listen to Meher Baba M3

Listen to Meher Baba M4 (Signal Box)

Listen to Meher Baba M5 (Vivaldi)

Listen to Baba O’Riley demo

971104 Arpeggio Piano: “This piece was recorded to DAT tape at my home in London on 4th November 1997. When I first moved into the house in London in which I now live I chose the tiniest room (an ante-room off the main living room) and set up a Kurzweil MIDIboard 88 note heavy action keyboard on which to practice and compose. Built into it are a wide number of arpeggio 'algorithms'. I used the keyboard everyday for about a year, recording to DAT tape or cassette. When Helen Wilkins started to compile this collection I completed some of these pieces by editing them on Synclavier and orchestrating the result on the computer.” [Scoop 3 liner notes] Listen to 971104 Arpeggio Piano

Variations On Dirty Jobs: "This was recorded on piano on 7th November 1997 and completed in February 2001. I fully orchestrated it earlier this year. Although the chords are similar to Dirty Jobs from Quadrophenia it is an entirely original composition. It is intended to demonstrate the kind of tonal effect I could achieve should I develop a full orchestral version of Quadrophenia. The piano was recorded on a Kurzweil sequencer and later 'quantized' to a DAT machine. I then copied the DAT to my Synclavier hard-disk system and tightened it up, then added the orchestral parts using all synthetic sounds. The opening cascade of the piece is written in 7/8 time. It intentionally created a chaotic but processional sound. Later it becomes more conventional, but the piano arpeggios in the middle are difficult to play if you don't happen to use my particular 'three fingers on the right one finger on the left' two-hand technique. Although the piano sounds as though a computer has produced it, in fact all that has happened to my free part is that it has been 'quantized'. That means any out of time notes have been brought back into time, it gives it a real concert-pianist feel, but it's partly a bluff. It is, by the way, only the middle part that is 'quantized'." [Scoop 3 liner notes] Listen to Variations On Dirty Jobs

How Can I Help You: Pete describes his recording process and use of synthesisers to add the orchestration on How Can I Help You.

Guantanamo: “Technically this was created in rather a laborious way. I recorded a long organ drone using my vintage Yamaha E70 organ (used many times by me on Who and solo recordings in the past), and then cut it into something that sounded like a song using a feature unique to Digital Performer called ‘chunks.’ This creates blocks of groups of tracks that can be assembled and disassembled easily, like cutting multitrack analogue tape with a razor blade, but with less blood. The lyric grew out of the implicit angry frustration in the organ tracks.” [Rolling Stone May 19, 2015] Listen to Guantanamo

Lifehouse Method – data generated electronic music

In 2007, Pete launched the Lifehouse Method software system that was designed to generate unique pieces of electronic music processed from various personal data that a user input into the website interface. Pete composed the song Fragments around one of the early Method sample pieces produced for the system by Lawrence Ball, which was released on The Who’s Endless Wire album in 2006. For more information, please visit the Lifehouse Method page. “The music that comes out of the Method software has been generated by a musical process that Lawrence Ball created. I first met Lawrence when we were engaged together in a music festival that he does every year called Planet Tree. Lawrence invited the American composer Terry Riley. I was a big fan of Terry Riley, and in the 70's used Terry Riley and the Indian teacher Meher Baba for one of my first experiments in this particular process. The music that came out of that was called Baba O'Riley, Baba for the Indian teacher and Riley for Terry Riley. Put the two things together and produced a song now which to this day is the one that for some reason, particularly American audiences, go crazy about. I don't know if it's the music or the lyrics, the refrain ‘it's only teenage wasteland’ is the one they love the best. But the ripply sound in the background is the characteristic sound that was produced when I started to program and work as a serious electronic music composer. Lawrence invited Terry over, he did a concert, we met, and then I listened to Lawrence's work and I loved it, I just loved it. So, what is produced by the program is music that is generally music that Lawrence and I tend to like. Whether you like it is absolutely immaterial to us! [laughs] The composer is king in this respect. But what we are trying to do is we are trying to approach the truth from the data we get. And we are trying to produce something that is an authentic compositional reflection of the data that we get put in.

“The music that comes out of the Method software has been generated by a musical process that Lawrence Ball created. I first met Lawrence when we were engaged together in a music festival that he does every year called Planet Tree. Lawrence invited the American composer Terry Riley. I was a big fan of Terry Riley, and in the 70's used Terry Riley and the Indian teacher Meher Baba for one of my first experiments in this particular process. The music that came out of that was called Baba O'Riley, Baba for the Indian teacher and Riley for Terry Riley. Put the two things together and produced a song now which to this day is the one that for some reason, particularly American audiences, go crazy about. I don't know if it's the music or the lyrics, the refrain ‘it's only teenage wasteland’ is the one they love the best. But the ripply sound in the background is the characteristic sound that was produced when I started to program and work as a serious electronic music composer. Lawrence invited Terry over, he did a concert, we met, and then I listened to Lawrence's work and I loved it, I just loved it. So, what is produced by the program is music that is generally music that Lawrence and I tend to like. Whether you like it is absolutely immaterial to us! [laughs] The composer is king in this respect. But what we are trying to do is we are trying to approach the truth from the data we get. And we are trying to produce something that is an authentic compositional reflection of the data that we get put in.

If you listen to [the Meher Baba piece], you will hear the raw material that I worked with to produce [Fragments], and I did a lot of things that are very obvious. I listened to the whole thing, which is a 5 minute piece, and I picked pieces, chunks of it. Firstly I discovered that the cycle was not an 8 bar, or a 4 bar, or a 16 bar cycle, it was 15 bars. So, every now and then you hear a little drum flange, which kind of adds the bar on what became a 12 bar cycle. I would take chunks that I liked the sound of, that felt to me fairly simple, but also to create the conventional ‘introduction - verse - chorus - verse - chorus - middle bit - verse - chorus – end’ that we are so used to in the current tradition of pop writing, at least conventional pop writing, the kind that I grew up with, and create a frame for it and then elaborate it. And you can hear to some extent that some of the lyrics are inspired directly by the sounds. For example, when I talk about snowflakes falling, the sounds felt to me like snowflakes falling, so I simply came up with that idea. The idea that we are fragments, we are pieces, we are coming together, this was a notion that came out of listening to many, many hours of Method music and thinking, ‘what does this feel like?’” [Lifehouse Method launch April 25, 2007] Listen to Fragments

Composing new songs with Jean-Michel Jarre

Pete collaborated with French electronic music composer Jean-Michel Jarre on Travelator Part 2, a brand new song that was released in October 2015 on Jarre’s album Electronica 1: The Time Machine. The album features artists who have inspired Jarre over the years. A three part EP of Travelator will be released soon.

“Pete was the first guy to introduce sequencers into rock music with songs such as Baba O'Riley. As one of the creators of the rock opera as a genre, he has an epic approach to performance that's quite close to my approach of performances for big concerts.” [Jean-Michel Jarre USA Today Aug 2015]

"When you take the idea of Pete Townshend, I mean you’d think, ‘Why Pete Townshend?’ Pete Townshend, he’s the guy who introduced electronic sounds and sequencers into rock music with songs such as “Baba O’Riley” and ‘Who’s Next.’ Also when I came to visit him in Richmond in the UK, I picked three different demos and we discussed a lot of things. We spent half a day in his kitchen drinking tea and talking about different things. Then, I played him the three demos that I had in mind. That’s always something difficult when you don’t know how the other person will respond. He immediately says, “I really love these three pieces. Why not do a mini electronica? I would be your lyricist in this and I will sing on it and I will play the guitar if you want.” And that was done in principle and we started from that. It pushed the track so far away by giving me so much. We were in the studio together and he was like a kid in his very earliest approach to music remains exactly the same. It was like he was a teenager." [Jean-Michel Jarre Artist Direct Oct 2015]

Credits

Produced, researched and written by Carrie Pratt

Then, when I had been about ten, at the Movietone News Theatre in Oxford Street I first saw the groundbreaking Disney animation feature ‘Fantasia’ which was projected with pioneering multi-channel sound. This film was my first exposure to true stereo sound. I had gone back at least ten times. Beautiful and powerful music literally intoxicated me long before I knew what intoxication was, and through this film with its complex and advanced audio recording I was to become a student and advocate of recording technology. At Ealing Art School’s lunchtime sessions, soon as a record began I could continue to sing it in my head." [Who He blog "Chapter 27" 2007]

Then, when I had been about ten, at the Movietone News Theatre in Oxford Street I first saw the groundbreaking Disney animation feature ‘Fantasia’ which was projected with pioneering multi-channel sound. This film was my first exposure to true stereo sound. I had gone back at least ten times. Beautiful and powerful music literally intoxicated me long before I knew what intoxication was, and through this film with its complex and advanced audio recording I was to become a student and advocate of recording technology. At Ealing Art School’s lunchtime sessions, soon as a record began I could continue to sing it in my head." [Who He blog "Chapter 27" 2007] "Kit came to see me at my Soho studio and I played him a few works in progress, songs about rabbits, fat people and 'Gratis Amatis', the opera dedicated to Kit and our beloved mutual friend the composer Lionel Bart. Kit asked whether I could put together a more serious pop-opera piece with several distinct strands, perhaps based around 'Happy Jack'. [...] Quick, quick, quick. 'A Quick One' became our new watchword and the title of the new album when it was finally released. I scribbled out some words and came up with 'A Quick One, While He's Away'. This became known as the 'mini-opera', and is full of dark reflections of my childhood time with Denny." [Who I Am autobiography 2012]

"Kit came to see me at my Soho studio and I played him a few works in progress, songs about rabbits, fat people and 'Gratis Amatis', the opera dedicated to Kit and our beloved mutual friend the composer Lionel Bart. Kit asked whether I could put together a more serious pop-opera piece with several distinct strands, perhaps based around 'Happy Jack'. [...] Quick, quick, quick. 'A Quick One' became our new watchword and the title of the new album when it was finally released. I scribbled out some words and came up with 'A Quick One, While He's Away'. This became known as the 'mini-opera', and is full of dark reflections of my childhood time with Denny." [Who I Am autobiography 2012]

"I had synthesizer backing tracks, which I already developed for some other pseudo orchestral elements, violins and horns and oboe. John Entwistle could play almost any brass instrument with valves and he put on trumpets, baroque trumpets, tubas, sousaphones and all kinds of things to complement what I’d done. By the time we finished, the demos sounded like a massive pseudo orchestra in places." [Amazon Front Row interview 2015]

"I had synthesizer backing tracks, which I already developed for some other pseudo orchestral elements, violins and horns and oboe. John Entwistle could play almost any brass instrument with valves and he put on trumpets, baroque trumpets, tubas, sousaphones and all kinds of things to complement what I’d done. By the time we finished, the demos sounded like a massive pseudo orchestra in places." [Amazon Front Row interview 2015] I started this work about 17 years ago. Mainly looking at my rock operas and mini-operas. Billy Nicholls, Sara Loewenthal and Rachel Fuller were the main protagonists in ‘Angelic Ceilings,’ a group I put together to begin this work. Our first joint project was Lifehouse Chronicles in 2000. Finally, in 2012 I decided to commission someone to start on Quadrophenia. I didn’t have to look far because by this time Rachel Fuller and I had lived together for a long time. Rachel was keen to take this on. By a coincidence, I had first met Rachel when The Who were rehearsing at a London studio for the 1996-1997 tour of Quadrophenia that grew out of the charity performance I organized in Hyde Park for the Prince’s Trust, of which I had been a patron and activist since 1982. On that occasion my very old friend Billy (Nicholls) had asked Rachel to orchestrate some of his solo work, and that’s how the connection was made." [Discussions Magazine May 27, 2015]