This month marks the 50th anniversary of The Who’s classic album, Who’s Next, which was released in August 1971. To celebrate, here is a deep dive into the history of Lifehouse, Pete Townshend’s lost concept behind the songs.

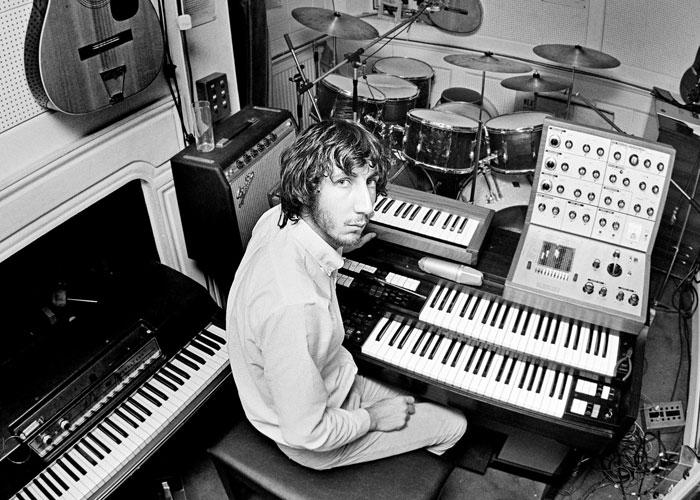

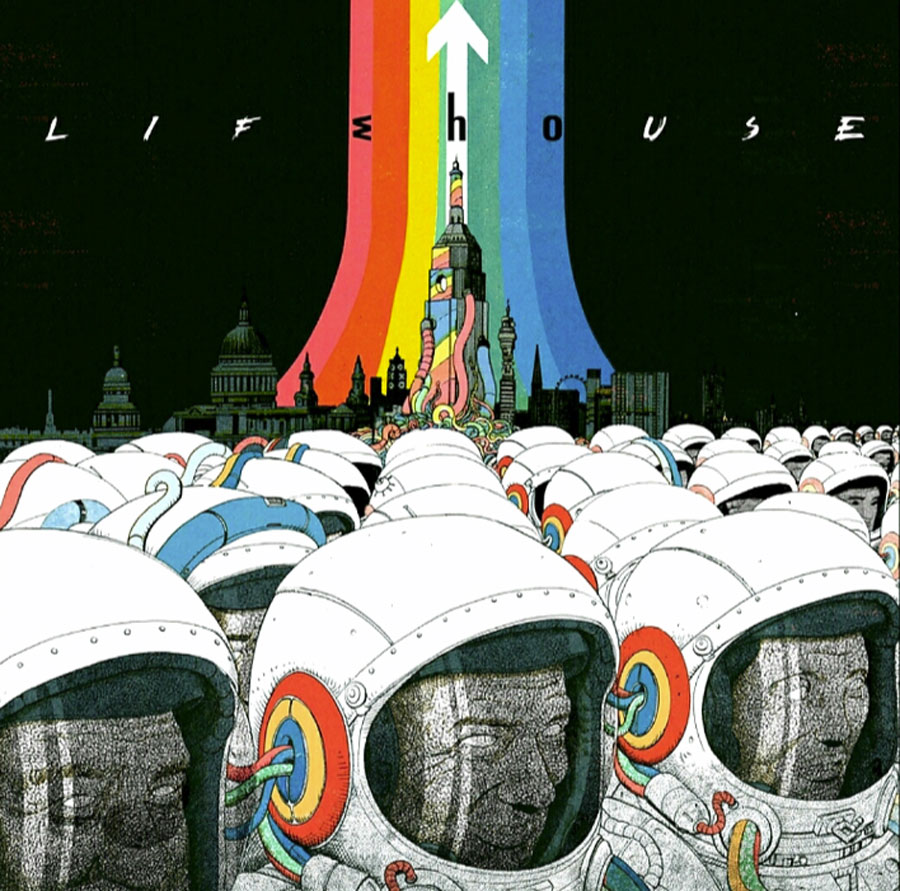

Lifehouse was envisioned to be a huge multi-media project that would follow up The Who’s smash hit rock opera Tommy. Pete developed a script for his story, which he hoped would be produced into a film, and recorded high quality demos in his home studio to provide a musical backbone for it. He first began experimenting with synthesizers while recording his demos for Lifehouse, and the revolutionary sounds he was able to produce using the EMS VCS3 and ARP synthesizers became the central soundscape behind Lifehouse. Pete’s goal was to push the rock art form to a new level of experience. If he was able to succeed, Lifehouse would have likely been the best work of his career. All the music that came out of it is fantastic.

The basic storyline of Lifehouse was set in the dystopian future, where the population lived in environmental life suits to protect them from extreme pollution following an ecological disaster. The suits were all hooked up to a universal grid, and they were force fed entertainment and life experiences from a huge media conglomerate controlled by the government. The grid was hacked into by a music composer named Bobby, who invited the audience to throw off their life suits and attend a big festival rock concert in person, or to tune in to participate on the grid. Each person sang their own unique song at the concert that was composed for them by Bobby in an experiment to produce music from their own personal data. At the end of the concert, all the songs were combined to create ‘the one perfect note.’ The army didn’t like the unofficial concert and tried to shut it down. When they broke into the concert, the whole audience was singing and dancing in a frenzied circle, then they suddenly disappeared in a kind of musical nirvana, along with the participants on the grid.

Many of the ideas in Pete’s Lifehouse script were prescient of things to come. The concepts of getting fed life experiences through a universal grid run by an all-powerful baron were a strong prediction of the internet, virtual reality, and online media moguls decades before they existed. The idea of people having to isolate and live in life suits to survive an environmental disaster is an eerie foreshadow of how society is dealing with climate change and contagious disease, especially now as our current population recovers from the Covid-19 pandemic that has forced so many people to work and live remotely. This all seems common place now, but in 1971, Pete’s story was a little too far fetched for most people to understand, and he had a difficult time explaining it.

The Who held a series of concerts at the Young Vic Theatre in Waterloo, London, which were meant to be an interactive experience with the audience and filmed as part of the Lifehouse project. The idea was to have the same set of people attend shows for a few months, so songs could be composed for them by feeding their personal data into a computer, and using tapes and synthesizers. Pete and Bobby Pridden set up a quadraphonic sound system and developed a tape system and hardware for their musical experiments. The new theatre was quite small for The Who, with a capacity of around 400, providing an intimate setting for the planned project.

Work at the Young Vic began on January 4, 1971, with a rehearsal to test out the theatre acoustics and sound system. They ended up throwing the doors open to anyone passing by. On January 13, Pete held a press conference to announce the Lifehouse project. The first official sessions began on February 14 & 15, with an invited audience of 200 lucky fans. More shows were held on February 22, March 1, April 26, and May 5.

Pete worked with Young Vic theatre director Frank Dunlop to help get his Lifehouse vision off the ground, but gave up on the idea after a few performances. He was promised a large budget for his film from Universal Pictures to help fund the experiments, which never materialized. His grand plans for audience interaction were reduced to just playing regular concerts to small invited audiences, and random people off the street. The Young Vic shows were never filmed, but some were recorded by Andy Johns (producer Glyn Johns brother) using the Rolling Stones mobile studio, including the April 26 show which was released on the 2003 Who’s Next Deluxe Edition.

After the collapse of the film project, The Who headed to New York City to record the Lifehouse songs at Record Plant Studios. The week long sessions, which began on March 15, 1971, were produced by The Who’s manager Kit Lambert and engineered by Felix Pappalardi and Jack Adams. Other musicians brought in to record included Leslie West (guitar), Al Kooper (organ), and Ken Ascher (piano). The sessions went pretty well, but Kit was acting erratic and was strung out on drugs. Pete was drinking heavily, and was very stressed out after the failure of his film plans and his inability to clearly communicate his ideas for the Lifehouse project. The Who ended the recording sessions early, and came back to London.

Glyn Johns was brought in to remix the Record Plant tapes, and he suggested they start over completely with new recordings with him as producer. In early April, they recorded Won’t Get Fooled Again at Mick Jagger’s Stargroves mansion, using the Rolling Stones 16-track mobile studio that they used at the Young Vic. The rest of the recording was done at Olympic Sound Studios in Barnes, London, starting on April 12 and finishing up in June, 1971. They had recorded enough tracks to put together a double album, and Pete attempted to sequence the songs in an order that would tell the Lifehouse story. He met with Glyn Johns and tried to explain the story, but Glyn failed to understand the concept and suggested they scrap Lifehouse completely and just put together a standard Who album instead, sequencing the songs in a way that worked best musically rather than try to fit a storyline. They dropped half of the songs, added a song by John Entwistle, and released a single album which became Who’s Next. Pete’s dream of Lifehouse came to an end.

Pete Townshend revisited Lifehouse in 1999, when he wrote a script that was adapted by Jeff Young for BBC Radio Drama. The radio play was directed by Kate Rowland, recorded in July 1999, and aired on BBC Radio 3 Sunday Play on December 5, 1999. The actors were David Threlfall (Ray), Phillip Dowling (Ray Boy), Geraldine James (Sally), Kelly Macdonald (Mary), Shaun Parkes (The Hacker), and Charles Dale (The Caretaker). The radio play was later released on CD by the BBC Radio Collection, and the script was published in 1999 by Simon & Schuster Pocket Books. Autographed copies of the book were available on Pete’s eelpie.com online store.

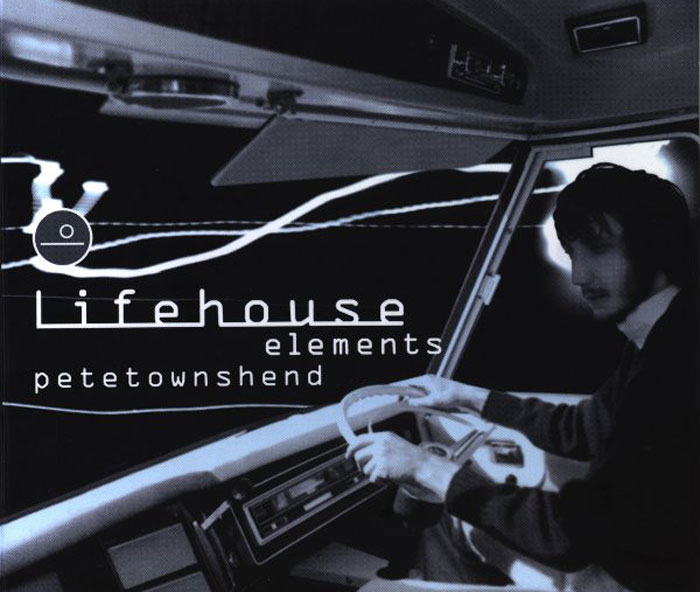

A couple of months after the radio play, Pete released the massive Lifehouse Chronicles box set on February 17, 2000. The set contained 6 CDs of Lifehouse material, and a nice booklet that included a long introduction by Pete, an essay on the history of Lifehouse by Matt Kent, lyrics to the Lifehouse songs, and a script for the Lifehouse radio play. The CDs included Lifehouse demos, themes and experiments, arrangements and orchestrations, and the BBC radio play. The boxset was released on Pete’s Eel Pie label, and was sold through eelpie.com. Lifehouse Elements, a CD sampler of the boxset, was released on May 23, 2000 by Redline Entertainment.

To promote the Lifehouse Chronicles release, Pete put on a couple of concerts at the Sadler’s Wells theatre in London on February 25 and 26, 2000. He was supported by the London Chamber Orchestra and a stellar group of musicians including Chucho Merchán (bass), Phil Palmer (guitar), John ‘Rabbit’ Bundrick (keyboards), Peter Hope-Evans (harmonica), Jody Linscott (percussion), Gaby Lester (violin), and Billy Nicholls, Chyna, and Cleveland Watkiss (backing vocals). The 2-disc CD titled Pete Townshend Live: Sadler's Wells 2000 was released on Eel Pie September 18, 2000, and was sold on eelpie.com. The DVD titled Pete Townshend – Music from Lifehouse was released in 2002. Pete shot videos of the band rehearsals that took place at his home studio in London the week leading up to the concerts, which were posted as a series of video diaries on his website petetownshend.co.uk.

Some of the ideas from the Lifehouse story have cropped up in later concept projects, including Pete Townshend’s 1993 solo album, Psychoderelict. The story features the character Ray High, a washed up rock star who has lived as a recluse for years dreaming about a musical project that he abandoned years before called Gridlife. The storyline draws on elements from Lifehouse, and includes synthesizer demo recordings from that period which are interspersed throughout the Psychoderelict production.

The Ray High character from Psychoderelict and other ideas from Lifehouse were brought back years later in The Boy Who Heard Music, a novella that Pete posted on his Blogspot site in 2005. The story was posted as chapters on his blog, and Pete encouraged interactive comments from his followers. The story was condensed into a 6 song mini-opera called Wire & Glass, which was released by The Who as an EP on July 17, 2006, and was included on their 2006 Endless Wire album. The Who performed Wire & Glass live often on the first leg of their 2006 tour.

Pete Townshend’s ultimate vision in the Lifehouse was to bring a large group of people together in a celebration concert to listen to music that was uniquely composed for each individual, with a grande finale that combined all the pieces together. In 2007, Pete attempted to bring his vision to reality, and launched the Lifehouse Method, which was a software system designed to generate unique pieces of music processed from various personal data that a user input into the website interface. The songs generated by the system were considered to be authentic musical ‘portraits’ of the ‘sitters’ who took part in the Method experiment. The Lifehouse Method was created by mathematician and composer Lawrence Ball and software engineer Dave Snowdon, who worked closely with Pete throughout the design and development of this unique and groundbreaking musical portraiture system. The lifehouse-method.com website launched on April 25, 2007, and over a 15 month period generated around 10,500 musical portraits before it was closed in 2008. The planned Lifehouse Method concert for sitters to gather and celebrate a performance of their portraits never took place. In 2012, Lawrence Ball released Method Music, an album of elaborated music created for the Lifehouse Method project. The album contains a track called Meher Baba Piece that is similar to the intro to Baba O'Riley. Pete used it as a basis for his song Fragments that was included in The Who’s 2006 Endless Wire album.

In an interview with Uncut earlier this year, Pete said that he was planning something big for the Lifehouse anniversary, including a graphic novel and possibly a documentary. He is reviewing some of the ideas that were lost as well as some of the experimental electronica work he did on Lifehouse Chronicles and Lifehouse Method, and may possibly work with other musicians to explore material that is inspired by the new graphic novel. Hopefully something amazing will come out soon!

To celebrate this milestone anniversary, here is the history of Lifehouse in Pete Townshend’s own words, sourced from various interviews and writings over the years.

One perfect note

The Pete Townshend Page, Melody Maker, September 19, 1970

Here's the idea, there's a note, a musical note, that builds the basis of existence somehow. Mystics would agree, saying that of course it is OM, but I am talking about a MUSICAL note. There is air that we breathe, we swim in it all our lives, we love it with our physical being and we watch it sustain the world around us. We seem adaptable and receptive to almost everything it produces; but most of all, and this has little to do with the essence of survival, most of us enjoy music. I've never been able to quite get to grips with how it all comes about, but artists and writers outside of music have noticed it too.

Pete Townshend interview, Disc and Music Echo, October 24, 1970

I've got kind of a pivotal idea, basically based on physics, closely linked with the things mystics have been saying for a long time about vibrations in music. Basically, it's about someone trying to discover that note that says everything, the essence, if you like, a musical sort of infinity. But, as we are not capable of finding it, he doesn't find it. It's a cyclic idea, a bit lame at the moment.

Pete Townshend interview with Penny Valentine, Sounds, January 2, 1971

Well one barrel [of Lifehouse] is fiction in the way Tommy was fiction. It has music, a story, adventures in it. On the other side is the story about man's search for harmony and the way he does it is through music. Through going into this theatre and setting up certain experiments... the general thing is that I'm attempting to do… to mirror with rock music the creative process - creation if you like. But the reason why this has to be done is the insinuation I'm making about the audience in the theatre. In other words they're attempting to find a piece of music which reflects the harmony of mankind, allows them to realise that you end up with a piece of music that is representative of the note. If you like, the thread of life. So I've been working on a piece of music that goes from the first single note – oneness – then it divides into twoness, then threeness, then it's rock music. Then it wasn't to be oneness again. From there we go to people. We're the notes, we're the divisions, we're the spearheads - the highest form of intelligence – and we're the people that have got the problem.

I'm not setting myself up as the Saviour of Rock Music. I just feel that the next step has to be made musically. That's why the whole accent of this thing is that music pervades everything - scientifically or mystically vibration is the source of everything. If you accept, for instance, that hydrogen is a note - which it is - then you must accept that humans, which are made up of walking collections of atoms and elements are cacophonies. That's what it's down to finding - a set of limitation we can work in and then accept the challenge and do it. And really we know we're no good just as mouthpieces of people. You have to look and challenge yourself.

The Pete Townshend Page, Melody Maker, February 13 1971

Our hero [of Lifehouse] is Bobby, the mystic-cum-roadie that puts all the fantasies in our heads into action, and gets results. He speaks for me now. "Music and vibration are at the basis of all. They pervade everything, even human consciousness is reflected by music. Atoms are at their simplest, vibrations between positive and negative. Even the most subtle vibrations detectable can effect us, as ESP or ‘vibes’. Man must let go of his control over music as art, or media fodder and allow it freedom. Allow it to become the mirror of a mass rather than the tool of an individual. Natural balance is the key. I will make music that will start off this process, my compositions will not be my thoughts, however, they will be the thoughts of others, the thoughts of the young, and the thoughts of the masses. Each man will become a piece of music, he will hear it for himself, see every aspect of his life reflected in terms of those around him, in terms of the Infinite Scheme. When he becomes aware of the natural harmony that exists between himself as a man and himself as part of creation he will find it simple to adjust and LIVE in harmony."

Serious chap this Bobby. He is a superstar no less. He goes on to say, "We can live in harmony only when Nature is allowed to incorporate us into her symphony. Listen hard, for your note is here. It might be a chord, or a dischord. Maybe a hiss or a pulse. High or low; sharp or soft, fast or slow. One thing is certain. If it is truly your own note, your own song, it will fit into the scheme. Mine will fit yours, and yours will fit his, his will fit others. You are what you are, and where you are, because that is what IS. To realise the harmony, that RIGHTNESS about your own note; even your own life, however you feel it could be improved by change, it has to be revealed. It can only be revealed by your own efforts."

The story of Lifehouse

Pete Townshend interview, Disc and Music Echo, October 24, 1970

It's about a set of musicians, a group who look like The Who, and behave remarkably like The Who, and they have a roadie who is desperately interested in ideals for humanity. It's basically a science-fiction fantasy idea. This roadie is wrapped up in electronics and synthesizers. He is fanatically serious about finding ‘The Note’ and spends all his time converting Egyptian charts and musical mysticisms into an electronic circuitry – and discovers all these wonderful and weird oscillations. He's fantastically serious, but the group isn't. Anyway this group find a note which, basically, creates complete devastation. And when everything is destroyed, only the real note, the true note that they have been looking for, is left. Of course, there is no one left to hear it; except the audience, of course, who are in a rather privileged position.

Pete Townshend interview with Penny Valentine, Sounds, January 2, 1971

The whole thing is set in the future and yet it could be now, the way we're going. Society's completely overpopulated, it's polluted, it's on the brink. The most human thing anyone could do is set off the bomb, only nobody can find the switch. So what happens is that like today, at one end you have this fantastically advanced scientific thing and at the other end electricity workers living off 13 quid and so on. So the two ends have drifted even further apart. You've got a lower low and a higher high and as a last resort this theatre is set up as a focus for everyone. In other words it's the last hope of humanity. If these people in this theatre can find themselves and balance in the midst of all this chaos then through very futuristic media things – experience suits, holograms and things – everyone else can, they can get above it and lose the illusion all around them. And underneath it all is the fact that in this theatre the Who are actually trying to DO something. Whether we succeed or not is another story. At worst we'll come out with something like Let It Be. I mean at worst.

Pete Townshend interview, New York Times, February 7, 1971

It's a sort of futuristic fantasy, a bit science fiction. It takes place in about 20 years, when everybody has been boarded up inside their houses and put in special garments, called experience suits, through which the government feed them programs to keep them entertained. Then Bobby comes along. He's an electronics wizard and takes over a disused rock theatre, renames it the Lifehouse and sets it up as an alternative to the government programs. Next, he chooses a basic audience of about 300 people and prepares a chart for each of them, based on astrology and their personalities and other data: and from their charts he arrives at a sound for each of them – a single note or a series, a cycle or something electronic – anything that best expresses each individual. I don't want to go into incredible detail, because I'll probably change it all: but the basic idea is that Bobby takes these sounds and builds on them and through them the audience begins to develop. First they attain a state of harmony, then a state of enlightenment and they keep growing all the time. On the Lifehouse stage there is a rock group, which will be the Who, to comment on the sounds and celebrate them. But they aren't the heroes and neither is Bobby. The real center is the equipment itself, the amps and tapes and synthesizers, all the machines, because they transmit the sounds: The hardware is the hero. Anyhow, the Lifehouse gets more and more intense, until Bobby takes over the government programs and replaces them with the new sounds, so that everyone wearing the experience suits gets plugged into them and shares them, and it goes on – the sounds keep developing, the audience keeps attaining higher states and, in the end, all the sounds merge into one, like a massive square dance. And everyone starts bouncing up and down together, faster and faster, wilder and wilder, closer and closer and closer. And finally it gets too much, the energy, and they actually leave their bodies. They disappear.

Pete Townshend interview, Zigzag, October 1971

The whole thing was based on a combination of fiction – a script that I wrote – called the Lifehouse which was a story – and a projection within that fiction of a possible reality. In other words it was a fiction which was fantasy, parts of which I very much hoped would come true. And the fiction was about a theatre and about a group and about music and about experiments and about concerts and about the day a concert emerges that is so incredible the whole audience disappears. I started off writing a series of songs about music, about the power of music and the mysticism of music.

Pete Townshend interview, Penthouse, December, 1974

Lifehouse was an aborted film script. The essence of it's story line was a kind of futuristic scene, a fantasy set at a time when rock and roll didn't exist. The world was completely collapsing and the only experience that anybody ever had was through test tubes. They lived TV programs, in a way everything was programmed. Under those circumstances, a very, very, very old guru figure emerges suddenly and says, 'I remember rock music, it was absolutely amazing, it really did something to people.' And he talked about a kind of Nirvana people reached through listening to this type of music. The old man decides that he's going to try to set it up so that the effect can be experienced eternally. Everybody would be snapped out of their programmed environment through this rock 'n' roll induced liberated selflessness. Then I began to feel, 'Well, why just simulate it? Why not try and make it happen? If it doesn't, well okay, we'll spoof it.' And so I became obsessed with really trying to make it happen, and Lifehouse would be the film of the event. I was talking wildly about a six-month rock concert, hiring a theatre for it, and having a set audience with a closed house of maybe 2000 people. I was going to write a theme for each individual, based on a chart that told everything from their astrological details to alpha waves to the way they danced to the clothes they liked, the way they looked – everything. All these themes would be fed into a computer at the same moment, and it was all going to lead to one note. All these peoples themes put together would equal one note, a kind of celestial cacophony. I did a lot of experiments, and it was practical; it wasn't just a dream. I was working at it.

Pete Townshend interview, NME, August 12, 1978

Basically it's a story about music, the rediscovering of music and what music is. It's not just about rock and roll, it's got a mystical quality. Seven years later a lot of what I wrote about has since become accepted, particularly in America, where they're into metaphysics, the connection between your mood and the way you live your life, and the vibrations in the air. It was all spacey talk when I first started. The rest of the band thought I was insane.

Pete Townshend interview, BBC radio, 1990

The story was a kind of allegory, a bit like Close Encounters or ET in the modern world, or possibly Fahrenheit 451. It was allegorical. I used music as a representation of good or evil. I set the story in the far distant future, not to give it a Sci-Fi thing but to try to break our preconceptions about music and entertainment. I tried to explain what I felt is happening to us in the modern world. Both to attempt to explain how rock music works and why I think it’s such a good force, but also to explain why so much entertainment is so subversive and corrupt in so many ways, in the way that it influences us. And so what I did was I took those two ideas and made them a fictional story. I had these goodies and baddies, and the baddies were the people who did the entertainment, you know, the people who gave us programs through television and intravenously. The goodies were the savages who had kept rock and roll as a primitive force and had gone to live with it in the woods. The story was about these two sides coming together and having a brief battle. It was kind of a simple adventure story with an allegorical theme going through it, which was just about the nature of music, both it’s power to communicate good ideas and good feelings, but also it’s power as a mystical, spiritual force.

Pete Townshend Introduction, Lifehouse Chronicles, December 1999

Briefly, the story of Lifehouse as it was presented to The Who in 1971.

A self-sufficient, drop-out family group farming in a remote part of Scotland decide to return South to investigate rumours of a subversive concert event that promises to shake and wake up apathetic, fearful British society. Ray is married to Sally, they hope to link up with their daughter Mary who has run away from home to attend the concert. They travel through the scarred wasteland of middle England in a motor caravan, running an air-conditioner they hope will protect them from pollution. They listen, furtively, to old rock records which they call 'Trad'. Up to this time they have survived as farmers, tolerated by the government who are glad to buy most of their produce. Those who have remained in urban areas suffer repressive curfews and are more-or-less forced to survive in special suits, like space-suits, to avoid the extremes of pollution that the government reports.

These suits are interconnected in a universal grid, a little like the modern Internet, but combined with gas-company pipelines and cable-television-company wiring. The grid is operated by an imperious media conglomerate headed by a dictatorial figure called Jumbo who appears to be more powerful than the government that first appointed him. The grid delivers its clients’ food, medicine and sleeping gas. But it also keeps them entertained with lavish programming so highly compressed that the subject can ‘live out’ thousands of virtual lifetimes in a short space of time. The effect of this dense exposure to the myriad dreamlike experiences provided by the controllers of the grid is that certain subjects begin to fall apart emotionally. Either they believe they have become spiritually advanced, or they feel suffocated by what feels like the shallowness of the programming, or its repetitiveness. A vital side-issue is that the producers responsible for the programming have ended up concentrating almost entirely on the story-driven narrative form, ignoring all the arts unrestrained by ‘plot’ as too complex and unpredictable, especially music. Effectively, these arts appear to be banned. In fact, they are merely proscribed, ignored, forgotten, no longer of use.

A young composer called Bobby hacks into the grid and offers a festival-like music concert – called The Lifehouse – which he hopes will impel the audience to throw off their suits (which are in fact no longer necessary for physical survival) and attend in person. ‘Come to the Lifehouse, your song is here’. The family arrive at the concert venue early and take part in an experiment Bobby conducts in which each participant is both blueprint and inspiration for a unique piece of music or song which will feature largely in the first event to be hacked onto the grid. When the day of the concert arrives a small army force gathers to try and stop the show. They are prevented from entering for a while, the concert begins, and indeed many of those ‘watching at home’ are inspired to leave their suits. But eventually the army breaks in. As they do so, Bobby’s musical experiment reaches its zenith and everyone in the building, dancing in a huge dervish circle, suddenly disappears. It emerges that many of the audience at home, participating in their suits, have also disappeared.

There is no dramatic corollary. I didn’t try to explain where they may have gone, or whether they were meant be dead or alive. I simply wanted to demonstrate my belief that music could set the soul free, both of the restrictions of the body, and the isolating impediments and encumbrances of the modern world.

Pete Townshend autobiography excerpt, Who I Am, 2012

I conceived the idea of Lifehouse in August 1970 in my big new camper bus, in which I stayed for a few days after playing the third Isle of Wight Festival. Although the complete story didn’t come together for another year, it was essentially one of a dystopia, a nightmare global scenario, a modern retelling of Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World. My hero in Lifehouse would be a good man, an advanced soul who would make a bad mistake and suffer the karmic repercussions. In the dark future I visualised in Lifehouse, humanity would survive inevitable ecological disaster by living in air-filtered seclusion in pod-like suits, kept amused and distracted by sophisticated programming delivered to them by the government. As with Tommy, people’s isolation would, in my story, prove the medium for their ultimate transcendence.

In my draft, I touched on some of the major anxieties of the times. When the Earth’s ecosystem collapsed, its inhabitants would have to drastically reduce their demands on the resources of the world. The allied governments of the world would join forces to demand that ordinary folk accept a long enough period of hibernation in the care of computers, in order to allow the planet to recover. What would make forced hibernation, plugged into a mainframe called the Grid, bearable? Only virtual experience, piped in through digital technology. What would free people from this forced hibernation? Live music and the Lifehouse. Rock music would be quickly identified by the controllers of the Grid as problematical. Because of its potential to awaken the dormant masses, rock music would be strictly banned.

A group of renegades and nerds would set up a rock concert, experimenting with complex feedback systems between the audience and the musicians, and hack into the Grid. People from everywhere would be drawn to the Lifehouse, where each person would sing their own unique song to produce the music of the spheres, a sublime harmony that would become what I called ‘the one perfect note.’ When the authorities stormed the Lifehouse, everyone would have disappeared into a kind of musical nirvana.

The Mysticism of Sound, a book written in the 1920s by Inayat Khan, a musician who became a Sufi spiritual teacher, was my inspiration for the story’s musical solution. The core of my idea was that we could all hear this music – and compose it – if only we would truly listen.

Electronic work on Lifehouse

Pete Townshend interview, Melody Maker, July 17, 1971

[The electronic music on Baba O'Riley] is the way we expected most of the music in the film to sound like because we have a pre-recorded tape of a synthesizer in the background.

Pete Townshend interview, In The Studio, January, 1995

It was a mixture of devices. It was using organs, which were getting pretty fancy then, and synthesizers together, and trying to find ways to synchronize the clocks together. Recording random sections of stuff onto tape, cutting tape up, re-recording bits of tape, cutting the tape up again, and getting rhythms from it. That was really what that was all about. I was really into… you know I had a studio in my house, and I had an 8-track tape machine and a dozen quarter inch machines, and a basement full of weird speakers, and echo units, and chains, and synthesizers, and oscillators, and all that kind of electronic music stuff. But what I was very good at was cutting tape. In those days electronic music was about cutting tape. I could do that and I could do it fast. Baba O’Riley has something like two or three thousand edits in it. The master tape goes by and it’s all white, it’s just sticky plaster from start to finish. What’s really interesting is the stuff that I was cutting out, I was sticking together on a reel to keep it tidy. And that piece is a really interesting piece of music in it’s own right. But what I then did was put a piano over the top, put a guitar, and a vocal, and made it seem more like rock and roll.

Pete Townshend interview, BBC Radio, May 1996

What was interesting about the [Putney unit from Electronic Music Studios of London] was that it was an educational tool. It taught you what oscillators could do. So, getting ahold of one of those little units, which I did like Roger Powell, I got one before I got my ARP, definitely educated me as to what was possible.

The problems inherent in the machine [was that it took ages to set things up]. You could set up a sound on its EMS, but if you wanted to go to the next one it's a couple of hours work. These days with digital machinery like on the Synclavier V you can hit a button and, well on the toys that you buy at Woolworth's now you can hit a button and you can get very, very complicated sounds to save and in those days we were stuck with this… there were no computers.

The reason why I, unlike other guitar players, I was actually able to get my mouth around this was that I'd always had a studio. What created the huge prospect of creative potential with synthesizers for me related to a spiritual link which I picked up from reading the Sufi message of Inayat Khan, two essays in particular, one called ‘The Mysticism of Sound’ and one called ‘Music.’ And I've just picked it up now and you can almost sort of open it up at random and find stuff which, like for example, (reads) ‘the soul feels buried in the outer material world and the soul feels satisfied and living when it is touched with fine vibrations. The finest matter is spirit and the grossest spirit is matter. Music, being the finest of the arts, helps the soul to rise above differences, it unites souls because even words are not necessary. Music is beyond words.’ The book was just packed with the kind of stuff which I knew from my work and I knew as an artist.

And when somebody came along and said, ‘Here is this device. It is a scientific device. It uses vibrations and oscillations and rhythms and blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, and it is also a musical instrument,’ I thought, ‘Well heigh-ho! Here is a link.’ And what it actually allowed me to do is that it allowed me to contemplate whether or not I could reflect exactly and precisely and scientifically the emotional, spiritual, disturbed state of a human being. And when I spoke to people like Powell and a few other people, particularly Tim Souster, their news to me was, ‘Yes, all you have to do is wait a little while and someone will create a computer that's fast enough to do this and because we can do this now but it's inordinately slow. And yeah, you could take your heartbeat and your mental alpha and beta patterns, anything that's recordable, ECG's, anything to produce data from an individual, shove it into a computer and out would come a piece of music.’ And the general consensus was that piece of music would reflect the state of the individual at the time. So, for me, getting hold of this big synthesizer was just a step, it was a promise, and I was always ahead, I was always one jump ahead. I've got the synthesizer, I'll learn how to work it, but now I want the computer. And it was the computer that never arrived.

Pete with the EMS "Putney" Synthesizer. Photo: Chris Morphet/Redferns/Getty

Pete with the EMS "Putney" Synthesizer. Photo: Chris Morphet/Redferns/Getty

Pete Townshend liner notes, Lifehouse Chronicles, 1999

I had planned to conduct rather simple experiments during these [Lifehouse] concerts producing pieces of music for some loyal audience members. In this experiment my most earnest champion was the late Tim Souster, composer-in-residence at Cambridge University and electronic music performer. He introduced me to Karlheinz Stockhausen and members of the BBC Radiophonics Workshop. I had no hope of producing anything like the expansive music I had envisioned and attempted to describe in my fiction, but certain people around me believed that was my target.

Pete Townshend interview, Synth History, April 27, 2020

[My first synthesizer was the] EMS VCS3. 1971. Tim Souster was helping me with my Lifehouse project. He introduced me to Karlheinz Stockhausen, Delia Derbyshire, Brian Hodgson (BBC Radiophonics Workshop) and helped me see the inevitability of wireless technology. (The story of Lifehouse was all about tubes and wires leading to Lockdown homes where people lived in Experience Suits). To be honest the main leap of understanding for me was the manual rather than the little synth. I suddenly realised what sound actually was, what timbre was, noise, frequency, etc. I still have a VCS3. I met its creator Peter Zinovieff recently and was surprised to hear him call it a ’silly little box’. Despite that I think he has great affection for it, but his dream was always computer music and now we all have that.

Photo: Chris Morphet/Redferns/Getty

Photo: Chris Morphet/Redferns/Getty

Lifehouse film project

Pete Townshend interview, Disc and Music Echo, October 24, 1970

The thing about an album and a film for The Who is that it gets us away from the stereotyped musical structures we've been confined to. It will be a challenge for us, but without deserting the rock structure. I feel that instead of dividing our rock pieces up into short pieces, it should be possible to create one great big powerful piece; one complete thing, but still sectioned off probably. So far it's gained much better reaction within the group than Tommy ever did. There will be more comedy in this one. Keith Moon and Viv Stanshall are working on that aspect. There is obviously scope for fantasy film. But it's got to be a serious piece with a humour thing interwoven with it. I think that's the secret of doing anything successful. You have to take what you're doing seriously but you mustn't necessarily be serious about yourself, all the time. I think it's going to happen as a record but I don't know whether it's strong enough for film.

Pete Townshend interview with Penny Valentine, Sounds, January 2, 1971

One of the reasons we want a film so badly now is that there should have been a film of Tommy, everybody knows that. But in the past when things like the Tommy project came up there have always been problems with it being too big for its boots, so big it's always ended up bum-steering itself out of being filmed. The point is now we really ARE making a film. I mean we're starting on February 1. We've got the place worked out, the whole military programme is set to go. People are arguing with unions – the whole thing is welding together. The only step we can take now with our music is just to take a visual step. We're not going to be acting. We're not going to be doing anything extraordinary in that area, but we are still wanting to produce the finest music we're capable of and, if possible, to kind of act as efficient catalysts as it were – moving rock out of the rut that everyone thinks it's in and everyone really knows it's in. I mean it's in a rut. It's not dead by any means but it's definitely stuck. What it needs – to use a revolutionary phrase – is more hardware. It needs more machinery, it needs more available to a composer. It needs more people to know that you can write far better on a tape recorder than without one. It needs people to realise that for a group today their talent lies as much on the engineers' ability to operate a PA system as their singers' ability to sing in tune. And the accent is moving all the time towards hardware – towards machinery.

We've done a rough story line in order to put in musical ideas now which might later be cut drastically or altered completely. I've written a lot of songs about what I think is going to happen, what I'd like to happen – the experiments working, quadraphonic experiments, 16-track recordings, 3D experiments. I'd like to see all that work together. At least we have a thread – a stimulus to get our teeth into now. A music for people to react to so they know what we mean and what we're doing and they don't walk into that theatre wondering what's happening. They go in knowing what they're there for and why. Knowing they can't just sit back and leave it to the Who – that it's as much up to them as everyone else and there is going to be some day in the distant future when THEIR piece of music – which I assume I'll be composing – will be played and people will react to it. The new album's tied up with the film so we've kind of started on the film first. I'm conserving a lot of material for this film thing. Admittedly I had words, I have pre-conceptions about the film music – I'm probably the only person that has an idea of what's going to come out of it. At the same time I'm holding back so that these numbers can be affected by the process of the filming.

Pete Townshend interview, Rolling Stone, August 5, 1971

The Who really had to be involved in something that was accelerating. After Live At Leeds we had just planed off, we had clichéd ourselves incredibly. I said 'fucked if I'm going to write another pop opera.' God knows what would have happened if I did. I figured we needed acceleration and the only possible area left is film. I was hoping that the Who could be involved in the next big exciting rock boogaloo that could change the whole rock movement. You know, things have been very sad lately and groups are doing the same old thing. In order to change the face of rock as much as the Beatles did, this new group, or entity, has to completely alter the rock theater. In other words, this group couldn't go to the Fillmore and do their debut. And it's not going to happen in two hours; it's going to be a six month thing. So it had to be a film, right? I started to build this thing, in fiction, about a guy who is IT. The next big superstar, the Supersuperstar. The one who does it all. And around this I'd build up a new technology. If I could get a couple of million dollars from some movie company, then I could get a thousand people and literally live and work with them in this theater environment for six months. The whole thing was taken on a sweeping scale of having them mirror the next big fucking incredible rock event in a film. It would be saying 'This is it, this is the way we're going to live from now on, this is going to be society.'

We got approval for the money from Universal Pictures and I went ahead, rapping to the group, writing the script. We got the quadraphonic PA. We developed some tape systems, I went into synthesizer things on how to get music out of personalities and this sort of thing. We changed the acoustics of the Young Vic so that we could have a level of entertainment day and night. I didn't want to invent a hero, obviously, but for the purpose of the script, I wrote him in and called him Bobby, as a gag. We developed an amazing set of hardware. I spent £12,000 ($30,000) on synthesizers alone. You know in FM radio they have cartridges where, as soon as you hit the button, out comes music? We've got this system where I've got this row of foot pedals, and when I hit one, something just comes out. It might be a brass band, a full orchestra, a plane going by, an explosion, whatever. The other thing I was working out on was a synthesizer to mechanically reflect the basic information about an individual, like height, weight or astrological detail, in music. My friend would make up a chart, then I would set the synthesizer up to certain parameters, then feed the eight-track into that and the synthesizer would mix the tapes on its own.

Well, the next thing you know the bottom starts falling out all around me. I find that I can't have the Young Vic every day of the week, only Mondays. It bombed, bombed out incredibly because it was too far out.

Pete Townshend interview, Time Out, August 27, 1971

I think what needs to happen now is some rock situation, possibly paid for by some film company, some rock situation which is real, which it creates itself and which because it happens on film will show the way if you like. But rock has got to be taken out of concert halls and football stadiums, and off records, and Radio One and AM radio and FM radio in the States, which began well but is now incredibly distorted and corrupt. I really look on the Who as one of the few bands that could ever pull it off. We've pulled it off before and I think we can pull it off again. We want to make a film. I'd like to get 2000 people and live with them for six months, feeding and clothing them, and not as a power trip, I mean I'd be included too. But what actually happened was that we got on the stage and people wanted to see the Who's new act. The Young Vic is after all a theatre, it's not a field. It would strike me as being an incredible scene if you could say I'm not going to buy a rock album, I'm not going to go and see a rock movie, I'm not going to go and hear a rock opera, what I'm going to do is go and live on a rock farm.

Pete Townshend interview, Crawdaddy, August 28, 1971

You probably know we started off this year trying to get a film together out of a theatre experiment. Well a lot of the songs have come out of that. So they've got a lot of technical niceties about them like synthesizer backing tracks, on which we play to. Others are just ordinary songs that come out of the air. We've got two albums, only one of which is being put out. The others being kept till we need it. To go into it at any length, it gets more and more confused, and that's why we broke down. I could see the finished product, but I couldn't explain how I thought we could get there. We did give the performances – that's the wrong word really – and Universal Pictures promised me a million dollars on the strength of a conversation. But The Who – and this includes me, because I need direction and production as much as anyone else – got more and more confused and tied up in technicalities like quadraphonic PA systems, and we just forgot how to play. With songs, I outline the idea to them and then make a demo. That's where this experiment fell down. You can't make a demo of a film. I wrote a script, but I'm not a scriptwriter so that wasn't overly well received. We got very very close to what would have been a revolution in rock and roll, but we didn't really have the fodder to carry it off. We had to stop being The Who for so long we realised it was going to take months to rebuild ourselves. So here we are, with no film. And I want to get a film done more than anything else. But we did get a lot of good material for the album.

Pete Townshend interview, LA Free Press, reprinted NME April 1, 1972

Well, there have been lots of breakups threatened – quite a few in the early days, like '65 and '66 just previous to us coming to the States. And one fairly recently when we were trying to get the Lifehouse film together. It sort of ended up me against the world – that sort of thing. In that particular case, I had one idea about what the group should be doing, and the group had another idea. Really, the whole thing about that occurrence was the fact that I felt that where the Who were at – and this probably still applies today – was very much a reflection, if you like, of what's happening to rock and roll as a whole. I felt we were capable of getting a film together and working on new formulas and things – new sounds on stage using tapes and using synthesis and just using all the technical things that are available, but also using a whole other sort of new energy from within the group, as well. And combining it all together in one fell swoop, we could really sort of capture what was going on. I mean we came out of the whole film problem with a fantastic amount of energy and zest just to play and just to have fun. We got so brought down by the problem of what we were trying to get into that we ran back and picked up the guitars and banged away – as if to say 'Fuck everybody.'

Pete Townshend interview, Penthouse, December, 1974

Lifehouse was an incredibly ambitious project, but it got entirely out of hand. Everybody was behind it; they just didn't understand it. The fatal flaw, though, was getting obsessed with trying to make a fantasy a reality, rather than letting the film speak for itself. And it hurt when I realised it was all a crazy idea. We needed people for example. So we opened up the theatre we rehearsed in and played a few unannounced concerts to try and get some flow of people coming through. All we got were freaks and thirteen year-old skinhead kids. If we had advertised the thing as a Who concert, we could have packed the fucking place for a year. But we were just opening the door and playing, waiting to see who came in. It was a disaster. It made me the most cautious I've ever been. The self-control required to prevent my total nervous disintegration was absolutely unbelievable. I flew to New York and did some therapeutic recording work, pieced myself together and went back to England to finish off Who's Next [which was] the remains of Life House.

Pete Townshend interview, In The Studio, January, 1995

I was working on a very ambitious piece at the time, for the time, called Lifehouse which was going to be a movie based on a live performance of The Who that was projected to last 5 to 6 days in a theatre called the Young Vic in London. And through that live performance were going to be spun a series of fictional stories that wove their way in and out of the concert. And the concert itself was all a part of the story. And off we marched into the land of mixing Hollywood film making and concert film making with science fiction and Sufism, and all kinds of other stuff. It was a very very big project for me, much bigger than I could handle. But I had a lot of fun working on it. The band were right behind me, they had absolute faith in me. About half way through the project, I realized that our managers were on hard drugs. They weren’t exactly undermining the project aggressively, but there was a problem. It was that Kit Lambert was representing to Ned Tanen [from Universal] that I was crazy, and that what we really wanted to do was make a movie of Tommy, this was before Ken Russell’s film, and that Lifehouse was in fact Tommy. And of course it wasn’t me that was crazy, it was Kit Lambert. But it did undermine the project, and for a while there I did think that I was crazy. I did go a bit nuts I think.

Since that day, a lot of things that seemed crazy at the time, are now common parlance. That whole idea of virtual reality – Grid Life – as I called it in those days. You know, William Gibson, his cyber punk books has introduced the idea of living on the internet, the cyber net or the matrix, jacking in and jacking out, or whatever. And we have an accepted notion of virtual reality as something which is going to be part of human entertainment and experience, and not just a way for US pilots to learn how to fly jets. So, a lot of those things actually happened now. So, it would be a good thing to look back on, but it’s very, very complicated. It was too big for me to deliver. I was just a guitar player, and I wrote rock songs. I didn’t know what the hell I was getting into. It was HUGE, absolutely huge! You know, I met Karlheinz Stockhausen, I was working with the composer in residence at Cambridge University, I was working with computer manufacturers, I had the first big guitar interface studio synthesizer in the world, I was doing all this stuff, all at once. I was learning about how the great Sufis had laced the spiritual life into quantum physics. I was just out of my depth!

Pete Townshend interview, BBC Radio, May 1996

Although I wasn't an expert screenwriter, there was a script there, there was a bunch of songs there, there were ideas there. All they had to do was to put me together with somebody who knew what they were doing, and we would have had an extraordinary project. What they actually did was they put me together with Frank Dunlop, who was the director of a small theatre, with nothing like the kind of credentials that he has today. They put me together with Frank and told him that we were working on Tommy!

Pete Townshend essay, BBC Lifehouse radio play, 1999

For twenty nine years I have been entangled in this thing called The Lifehouse. This was a project that 'failed', or the best part of the idea 'got away'. Sixties rock achieved so much in its first seven years, a short space of time in art and science, even in the modern world. My expectations of the rock form, the Who group, its managers and myself had been huge. In 1971, as the follow-up to my intimidatingly successful rock-opera Tommy, I wrote The Lifehouse for The Who, and there is no doubt that it was ambitious. The Lifehouse was first drafted as a film script. The film project stalled, but the rock album Who's Next was acclaimed as our finest. Songs like Won't Get Fooled Again, Behind Blue Eyes and Baba O'Riley, became part of the vertebrae of rock radio. A subsequent script re-write brought forth Who Are You and Join Together. It has always been a story, and vision of the future, which – when I reapproached it in 1974 and 1978 – inspired me musically, despite difficulties nailing down the dramatic side. And yet the narrative has always been a simple, accessible story. What was so difficult about the earlier versions? In the first draft of the 1971 film script was a fictional scene that, at the time, seemed almost inconceivable in reality. In the finale of the proposed film, members of an audience attending a concert provided personal data to composers working with powerful computers, and heard the results. Every single piece of music was then combined, and a mathematical, yet wonderfully creative, metaphor for the universality of the human spirit was demonstrated. This was fiction remember.

Lifehouse concerts at Young Vic Theatre

Excerpts from Pete Townshend’s speech at Young Vic press conference, January 13, 1971

We shall not be giving the usual kind of Who rock show. The audience will be completely involved in the music, which is designed to reflect people's personalities. We shall try to induce mental and spiritual harmony through the medium of rock music. We are going to use this theatre as a place to make music and for the audience to collaborate with the Who in making that music. We're interested in producing a fiction – a play, if you like, an opera, if you like, but neither of those descriptions would be entirely accurate. It will be a different kind of performance to the Who's usual. We've been playing rock music for a long time and we think we know a lot more than most groups about audiences. There is an harmony in The Who which has come from our music. When we give performance there is this elation, which is completely free of any drug stimulus, and it's from the fact that the music is good and the reactions are real. Theatre people will know that a really good performance will last in the audience's mind for months afterwards. We want to get this going in a permanent way. Our aim is to achieve a rock performance in a permanent way, so that when we and the audience get together in this theatre everyone will be involved and it will be achieved. I'm writing a fiction with a theme, a mood, a story, music and songs. Tied in with that is the fact that we're trying to break down audience preconceptions. I've been working on a tape that is meant to be a person. I feed into a computer a person's height, weight, age, date of birth, likes and dislikes and create a form of music that reflects that person's personality. I'll act as a computer and everything will be fed into me and processed, then put back out again. The effect is something that will come from everyone and the aim is that each person will get a better understanding of themselves. It will be the best music we've ever produced. Rock's real power as a liberational force is completely untapped so a new type of theatre, a new type of performance has to be devised to present it. If a film of this is made, it will become the first real rock film because it will reflect a reality.

Pete Townshend interview, New York Times, February 7, 1971

We're using the Young Vic because it's small and very close, with a capacity of three or four hundred, and it attracts a completely mixed up crowd, part theatrical hangers-on, part freaks, part Who fans. At first we will be playing there every Monday, but if the experiment works, if people keep coming back and going along with it, we might step it up to two or three or four nights a week, whatever is necessary. By the end of six months, anything might happen. I don't mean that I seriously expect people to leave their bodies but I think we might go further than rock concerts have gone before. I know that when live rock is at its best, which often means the Who, it stops being just a band playing up front and the audience sitting there like dummies. It's an interaction which goes beyond performance. We aren't like superstars, we're only reflective surfaces. We might catch an energy and transmit it, but the audience doesn't take more from us than we take from them, not when the gig really works. That's what we want to take further at the Young Vic: we want to see how far the interaction can be taken.

The Pete Townshend Page, Melody Maker, February 13, 1971

It really doesn't seem to be worth doing anything to me unless it can either do something for Rock or do something for its audience. The Who's coming performance and film work at the Young Vic will do both. Basically what we do could change our audience, our music, our status and even the way we walk. If it all doesn't change anything else it will change me. That can't be bad.

The Young Vic is a newly built theatre in the same street as the Old Vic. It was built especially to cater for young audiences, and the mood it puts across is one of adventure. Frank Dunlop, the adrenaline behind the place knows the limitations of regular theatre. We are beginning to feel the limitations of regular rock. Frank was originally interested in doing a production of Tommy. It was when we were discussing the possibility that we both realised that it couldn't do what we wanted it to do. We wanted it to attract both Rock audiences and the regular Young Vic theatre audience, but also break new ground, bring in totally new faces, young faces perhaps. Most important it had to freshen up the idea of an audience. Tommy might have been capable of doing that but we (The Who) didn't really have enough energy to carry 'Tommy' any further. We wanted something new, while we're about it it might as well meet our needs and aims more fully.

The aim is change. A change of life style for the band, a change of focus for our audience and a change in the balance of power that Rock wields. The music we play has to be tomorrow's, the things we say have to be today, and the reason for bothering is yesterday. The idea is to make the first real superstar. The first real star who can really stand and say that he deserves the name. The star would be us all. The Young Vic becomes the "Life House", the Who become musicians and the audience become part of a fantasy. We have invented the fantasy in our minds, the ideal, and now we want to make it happen for real. We want to hear the music we have dreamed about, see the harmony we have experienced temporarily in Rock, become permanent and feel the things we are doing CHANGE the face of Rock and then maybe even people. There is a story connected with each person that will walk into the Life House, but for now we have made one up for them, until we know the real one. We have music that will stimulate them to stay with us through lengthy marathon concerts, and perhaps even boring filming. We have sounds ready that will push us a lot further than we have ever gone before, but what the results will be is still unknown.

Pete Townshend interview, Melody Maker, July 17, 1971

We have really been trying to get the Young Vic thing together and begin the film there. It's a long story and it obviously went wrong because we haven't got a film and we won't have one. People will wonder why it took so much time but it did. Basically we were trying to be a bit too ambitious as far as changing the Who's sound and making technological advances which I thought were needed. The other thing was that we were wrong in choosing the Young Vic as a venue for the idea which we called the Lifehouse project. It's not going ahead now and, in fact, it's definitely finished. The album is all we have to show for it, apart from the experiments of playing with tapes. What we have to do now is rebuild ourselves because we were so heavily involved in the film idea. We did four shows before we started recording to try the new act out on stage. The audience knew that and so did the promoters. We are doing another three this weekend. We had to go back to gigging and find our feet again after the film business before we could start moving anywhere. The idea was not just the Who making a movie because it was the thing to do but because I thought that rock was failing at the moment to fully get through to its audiences. I sat down and thought about what the Who would be doing five years from now and how many rock songs I could write in that time which would adequately reflect the frustrations and anxieties of the young. Then I started to think about what kind of group would do this.

What we were going to do with the film was to put ourselves into the position of investigating a new kind of rock theatre. The idea was to get 2,000 people and keep them for six months in a theatre with us. The group would play to them and characters would emerge from them and eventually the group would play a very minor role. Maybe about 500 of the original 2,000 would stay during the six months and we would have filmed all that happened. But getting the idea through to film people was impossible. I don't know how those people can stay sane. I was forced to write a script and that became the Lifehouse script, just a name I thought of. We were wrong in choosing the Young Vic because we couldn't have it every night of the week and keep it for six months. Anyway there won't be a Who film now but we are still thinking about it.

Pete Townshend interview, BBC Radio, May 1996

I didn't regard the Young Vic performances as a dramatic workshop. I suppose I was waiting for that to start; I was waiting for that to happen. I'd done my bit, I'd written the script and the other stuff I was fussing with was technical stuff, really, trying to help the band play some of the songs that I had written, help Bobby with some of his technical stuff. And what we were doing at the Young Vic which was dicey was that we were working with a quadraphonic sound system which had been pioneered by [Pink] Floyd, it wasn't brand new, but, the desk that we were delivered may have worked, but Bobby Pridden couldn't seem to get it to work. That was one of the problems. He could work it, he could get it to work, but there was so many new things going on. Frank Dunlop had a mandate from the Young Vic to allow us in there as long as we were doing something that was manifestly for the public. So, he just started to invite people in off the street and all they did was just to get in the way, basically. We got nervous and we started to play "My Generation" and smash guitars and stuff.

(Reading) Each person present at the Young Vic for the finale is sure to have many preconceptions remaining, just like Bobby's fictional crowd. Hopefully they would all have been present at at least ten other concerts. It's unlikely but that would be an ideal situation. Some of the concerts would have been three days, some two and some of the earlier ones, only one. Any good characters that had emerged from the audience would have been filmed and perhaps even introduced into the story. Their influence might be so solid as to transform the fiction into something totally real. That's the aim, really, just as we start off with a group and an audience and hope to end up with neither, we start with a fiction which could very easily become shaded by the real events. People in the audience might even take over the parts of some of the major characters in the fiction as is. The finale itself would be long and involved but it would be working towards a final simplicity of straightforwardness.

Pete Townshend essay, BBC Lifehouse radio play, 1999

The first workshops of the project were held in 1971 at the Young Vic theatre under the direction of Frank Dunlop. My intention was that The Who would do a construction of the fictional Lifehouse concert, and the narrative part of the film would be made at a studio when we got the money. Frank arranged a regular weekly concert at the Young Vic, and, to justify me taking over the brand new subsidised theatre, held a press conference during which I explained the general idea. If you want to understand what I envisioned, you can listen to the Hacker in this play, breathing earnestly about what music can do. Tremendous confusion followed. I had planned to conduct rather simple experiments during these concerts producing pieces of music for some loyal audience members. I had no hope of producing anything like the expansive music I had envisioned and attempted to describe in my fiction, but certain people around me believed that was my target. Whispers of 'madness' fluttered backstage like moths eating at the very fabric of my project. Within a few weeks our 'experiments' had dwindled into trips to the local pub and over-loud short concerts of our early hits for anyone who showed up at the Young Vic. Universal Pictures, who had approved my script, never sent any money and my beloved mentor Kit Lambert, producer of Tommy, went off in a heroin-huff to live and work in New York. He was aggrieved I'd failed to help him realise his dream of directing a Tommy film and left me to stew. Eventually, exhausted and disillusioned, I abandoned the idea of making a film and started working on a straightforward recording. This became Who's Next, and the story of Lifehouse wasn't even mentioned on the sleeve. Several songs vital to the underlying plot were left off, Pure and Easy being especially important.

Pete Townshend interview with Matt Kent, petetownshend.co.uk, August, 1999

I knew what I needed [from the Young Vic] and I was just waiting for the money to come. If the money had come I would have either bought the Young Vic out, which was a possibility 'cause they were a subsidised theatre company with a mandate… a lot of people have forgot that I was on the board of the Young Vic, so I knew exactly what was going on and I knew that they couldn't mount productions without money. I said to Frank Dunlop if you give us this theatre for a couple of months, so we'd get to the point where we'd have a bit of a daily thing going here… we'd written some songs and we'd play to people who were coming in every day because they want to see how their music was coming on…we could take a portion of money from the budget and put it in the grant for them and you could use it for your first production of 'Waiting For Godot' or whatever it is you want to do. That side of it was very, very clear. My problem with the artistic director then, Frank Dunlop, was that he thought, by holding a press conference when he did in the first couple of days, that he could push forward the creative side of the production. What it actually did was to really put me on the spot and it confused the band.

So when John says 'We were all supposed to get together in the Lifehouse for fucking six months, I mean, where were we supposed to sleep?' We weren't supposed to sleep! In the film story they slept there because it was an encampment, a Glastonbury Festival type encampment. It was surrounded, I think, in the original script by a force field, you couldn't go home but, of course, the Who could go home. I knew they would go home, I knew that there would be nothing that could keep Keith Moon out of the clubs anyway! My intention was to use the place for as long as I could get it and was really bitterly disappointed when Frank Dunlop announced we could only have it for two days a week. What I needed was a daily experience, to be able to say to somebody that came in… on the first day I was asked 'does it matter if we let kid's in off the street?' and I said, no, do it and a couple of the kids I spoke to, I went up a said 'what's your name, where do you live and do you know anything about The Who?' They were so little they didn't know who The Who were. The idea that we played a bunch of Who hits to keep them quiet is bollocks because they wouldn't have known us from Adam, they were schoolchildren. I did actually say to one of them, 'If I write you a song will you come back tomorrow to listen to it?' and he said 'Yeah, I'll bring my mum and dad'. That was the kind of scenario that I was hoping for, something where we would start to build up what, I felt, would be a real mirror of what was going on already in the best pop music which was, that I write a song about you guys as a generality and then other 'you guys' type people identify with that process.

I was hoping for, at a maximum, to have gone in there for a couple of months but I thought I would get a couple of weeks out of it, particularly if I could pay for it. What happened was that no money came, I sat and waited and waited and no money came. You have to remember that we had the Young Vic for as long as we wanted before it opened, as long as we wanted. I used to go down there every day, it was empty for week after week after week. The film script was finished by the time the Young Vic was finished as a building. The building was finished; we could have gone in there any time… we were the first thing that ever happened in there. Kit Lambert introduced me to Frank Dunlop in the hope that Frank, as the Director of the Young Vic would not only give us a place where we could do the work but to give me a relationship with a skilled dramatist and theatre director, who would help me whip the story into shape. He had a copy of the script that I'd written but we never, ever had a script meeting.

No [the Young Vic shows were never filmed]. Well, John Hopkins of TVX was going to come along and film it. Hoppy was one of the people who ran the Indica bookshop, had run the UFO club and was a real pal of mine. What was interesting was that at that time they had the first black and white Sony 'handycams', the little brown ones, and I was going to videotape what the audience were doing, not the band. They were invited but again they wanted money. They only had one handycam, which I think was about a thousand quid, which is probably about ten grand by today's standard. So no, we didn't film it; we didn't get that far along. What happened was, and it's now well documented, is that we did a couple of nights there, a run through to get the quad sound sorted out the day after the press conference and then the next day we played to an invited audience. It seemed like nobody turned up, considering The Who were bigger than the Stones then, very few people turned up and so they let in some kids off the street, who immediately started to cause trouble. We were very sensitive about the new material, particularly anything that had synthesizers on it. We weren't always using tapes, sometimes I was using the original synthesizers and playing my guitar through them and stuff like that.

Pete Townshend autobiography excerpt, Who I Am, 2012

The crash I experienced after the second day at the Young Vic was immense, my fantastical imaginings having collided with reality. The high-flown writing, my grandiose theories in the Melody Maker, the scripts, technology, meetings pitching for money from Universal, the songs, the torturous struggle to do decent creative work while doing far too many live shows; it was all for nought. The Who made one more weekend appearance at the Young Vic, playing a load of old hits. I could see I had to give up on the Lifehouse project, or start all over again.

Lifehouse recording sessions

Pete Townshend interview, Zigzag, October 1971

We could have put together a really tight concept album I think. Roger thought so too at the time but Glyn Johns was very adamant that from his view as an observer he couldn't see any concept. And I think maybe he could have been wrong. I don't really know. I think that as a producer he perhaps stands a little too much away from the ethereal concepts that a group gets involved in because it's active, it's working and it's exciting and tends to just listen to what comes out of the speakers and take it at its face value without realising, of course, that a whole lot of people who are interested in The Who are very deeply into everything that we're doing, all of the time.

Pete Townshend interview, In The Studio, January, 1995

I had recorded the whole thing once at home, very carefully. My demos from that period are exemplary. The Who had recorded them again in rehearsal at the Young Vic. We had then come to New York, and with Felix Pappalardi and Leslie West we did a few recordings at the new Record Plant of some of the songs from Lifehouse, including a wonderful version of Behind Blue Eyes, a great version of Won’t Get Fooled Again, with Leslie West jamming away in the background. Then we realized that Kit, who was our producer at the time, was seriously strung out on heroin. We abandoned the session and came back to London, and went into the studio, really with me emotionally, physically, and spiritually collapsing.

Pete Townshend liner notes, Who’s Next, May 7, 1995

Kit called from New York where he was working at the new Record Plant producing Labelle. He said we should go to New York for two weeks and record the tracks with him. I remember being skeptical. Kit had been doing hard drugs (the rumour was that he had become a heroin addict). But he convinced me that he would co-produce with Jack Adams – a solid engineer I had worked with myself in New York. I felt happy at that moment as I am capable of being.

The New York sessions were great fun. We were the first band to use the revolutionary new Studio One – an early Westlake design – which opened during our sessions. It was a great experience, but very stressful. I remember drinking heavily and Kit was out of control. At one point during a kicking jam session at the end of Getting In Tune he ran out holding a little sign that said DON’T STOP! Of course by the time we’d all read this aristocratic but illegible scrawl we’d lost the magic. I asked for a group meeting at the Navarro Hotel the next day. As I walked into Kit’s room I heard him raging to his assistant Anja Butler: ‘Townshend has blocked me at every front. I will not allow him to block me this time.’ Something inside me snapped. I suppose it was hearing this man that I loved so much calling me by my surname, and with such anger. Perhaps I deserved it, but it devastated me. During the subsequent meeting, as Kit stamped around the room pontificating and cajoling, shouting and laughing, I began to have what I now know to be a classic New York Alcoholic Anxiety Attack Grade One. Everyone in the room transmogrified into huge frogs, and I slowly moved toward the open tenth floor window with the intention of jumping out. Anja spotted me and gently took my arm. There is no question in my mind that she saved my life. I was by that time a kook.

Home to London we went and – as the pliable, defeated (but very well rehearsed) anaesthetized basket-cases we had all become by this time – were easily processed in the Glyn Johns Hit-Machine of the day. At least I was. I think I procrastinated less than usual and Glyn and I hit off a long friendship and working partnership that amazed everyone who thought that two such hot-heads wouldn’t last an hour in the studio together.

With that I now think it would help to lay down the context of the recording sessions at the time. There were just four sessions in all.

1. The 1970/71 demo sessions at my home studio that produced two reels of songs which related directed or loosely to the film-script I had written, or were intended as padding to be replaced by experimental music produced during the Young Vic workshop.

2. The winter 1971 live recordings of the morale-restoring reality-facing performances at the Young Vic.

3. The spring 1971 New York sessions, which fell into two parts; a two day warm-up in Studio Two with Felix Pappalardi at the desk and Leslie West on guitar; the four-day session proper in brand new Studio One with Jack Adams at or under the desk, Kit on the bathroom ceiling and me in the Remy Martin bottle.

4. The boozy Stargroves and subsequent highly disciplined and sober Olympic sessions of summer 1971 with Glyn Johns which produced the final album [Who’s Next] we all know and love.

Pete Townshend interview, BBC Radio, May 1996

We did this taping with Andy [at the Young Vic] and then we went and we did some shows to see how the tapes would work live and I think by that time I was starting to think, oh fuck it, what I'm going to have to do is we're going to have to make an album. I remember when Kit rang up to say, ‘Listen, you should come to New York.’ I remember thinking that this was just wonderful. Kit was going to save me. I remember going for a walk in the park and thinking, ‘Good old Kit, he's come to save me. He understands. This is simple. He and I will stand together and explain it to these fucking vegetables. They'll get it and we'll make the movie and they'll all understand.’ And when I got there, I realized that that wasn't going to be the case.