The Age of Anxiety: A Novel

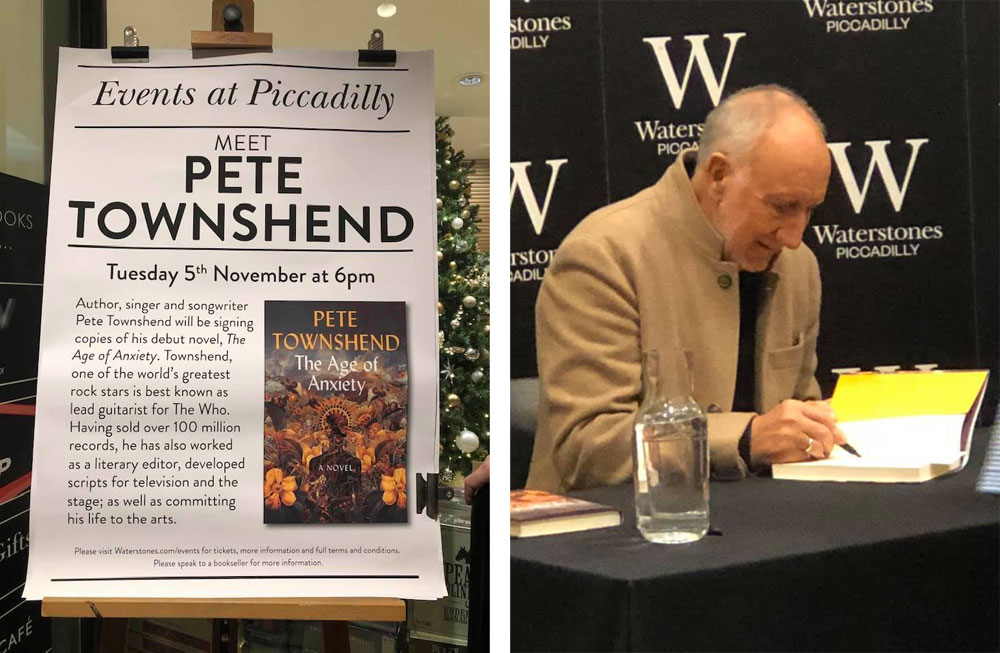

Pete Townshend released his debut novel The Age of Anxiety on November 5, 2019. The book was published by Coronet / Hachette Books, and is currently available in hardcover and audio read by British actor Michael Jayston. There are also plans for a paperback release later this year.

In The Age of Anxiety, Pete explores the anxiety of modern life and madness in a story that stretches across two generations of a London family, their lovers, collaborators, and friends. The editor, Coronet publisher Mark Booth said, “The Age of Anxiety is a great rock novel, but that is one of the less important things about it. The narrator is a brilliant creation – cultured, witty, and unreliable. The novel captures the craziness of the music business and displays Pete Townshend’s sly sense of humor and sharp ear for dialogue. First conceived as an opera, The Age of Anxiety deals with mythic and operatic themes including a maze, divine madness, and long-lost children. Hallucinations and soundscapes haunt this novel, which on one level is an extended meditation on manic genius and the dark art of creativity.”

The narrator of the story is Louis Doxtader, a dealer of Outsider Art in Richmond. He is the art agent for Paul Jackson, a sixties rock star and founder of the band Hero Ground Zero, who went mad and disappeared for years on the Cumberland moors, where he painted his apocalyptic visions of angels. The main protagonist of the story is Louis’s godson Walter Watts, a young rock musician who connects psychically to his audience and begins to hear soundscapes of their anxieties, which he describes in essays that are presented throughout the book. There are strong female characters interwoven throughout the story, including a woman named Floss, which was Pete’s early working title for the book. The story plot has many strands and a lot of twists and turns which all come together at a big concert performance of Walter’s soundscapes.

When starting work on the story in 2008, Pete Townshend drew inspiration from talking to people in his neighborhood around Richmond and found that there was a great deal of anxiety and fear on everyone's mind, something that is especially true in 2020. What could be a more apt description of the time we are currently living in than the Age of Anxiety? Like so much of Pete’s work over his career, he wanted to reflect his audiences thoughts and feelings. Many of the characters in the story are based on people he knows, and he sticks to subject matter he is very familiar with, such as the music business and art world. Readers familiar with Pete’s work and life will recognize autobiographical elements throughout the book.

The publication of this book is just the beginning of what Pete has planned for The Age of Anxiety. He has discussed grand ideas for future projects based on the book, including producing an opera and art installation. Pete has composed music and has written a libretto that can be read at live performances. He has also commissioned orchestral music for the soundscapes. The film rights to the story have already been sold, so there may possibly be a movie too.

We look forward to any new music and performances that may come out of this project!

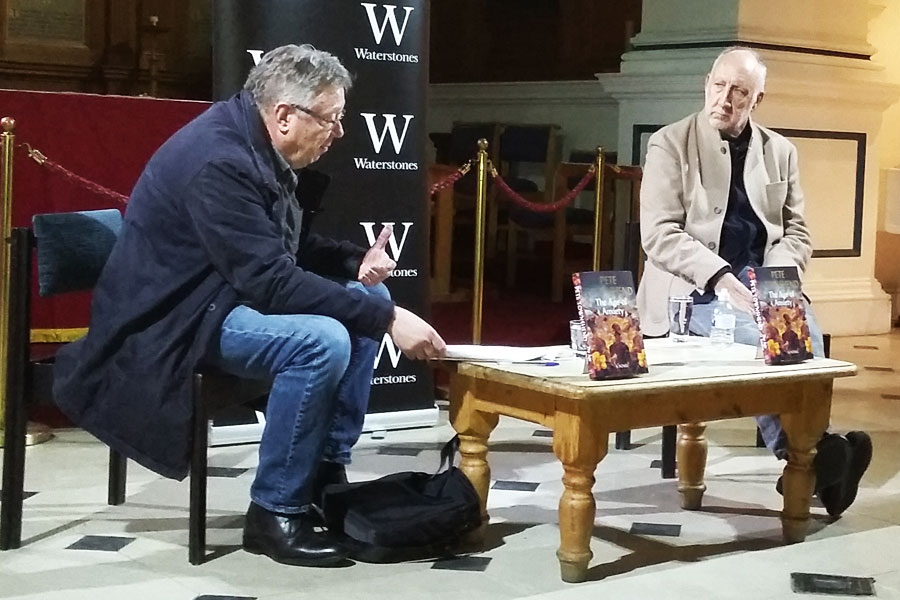

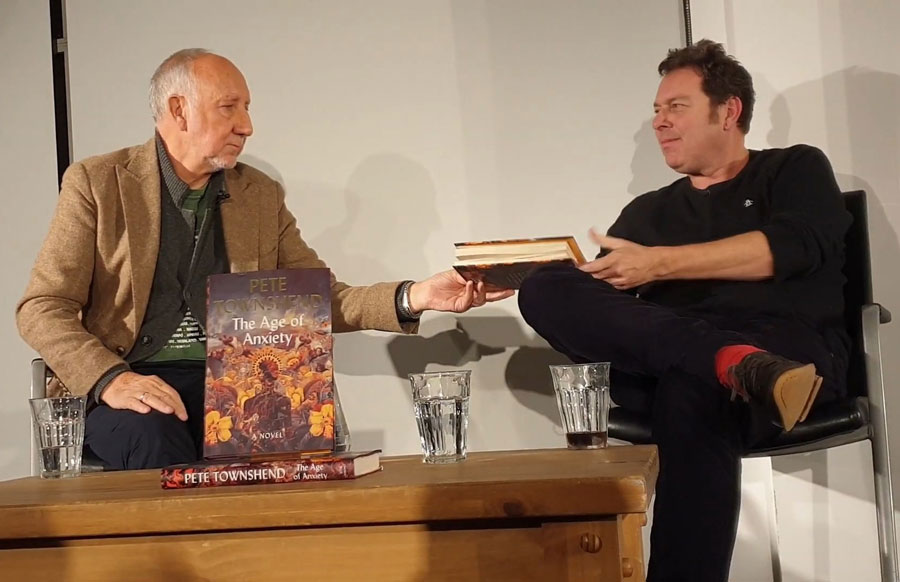

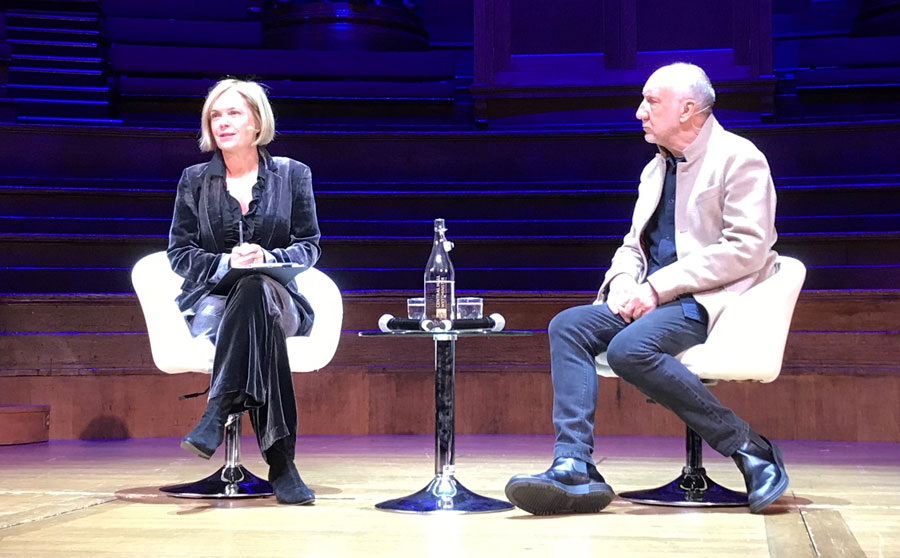

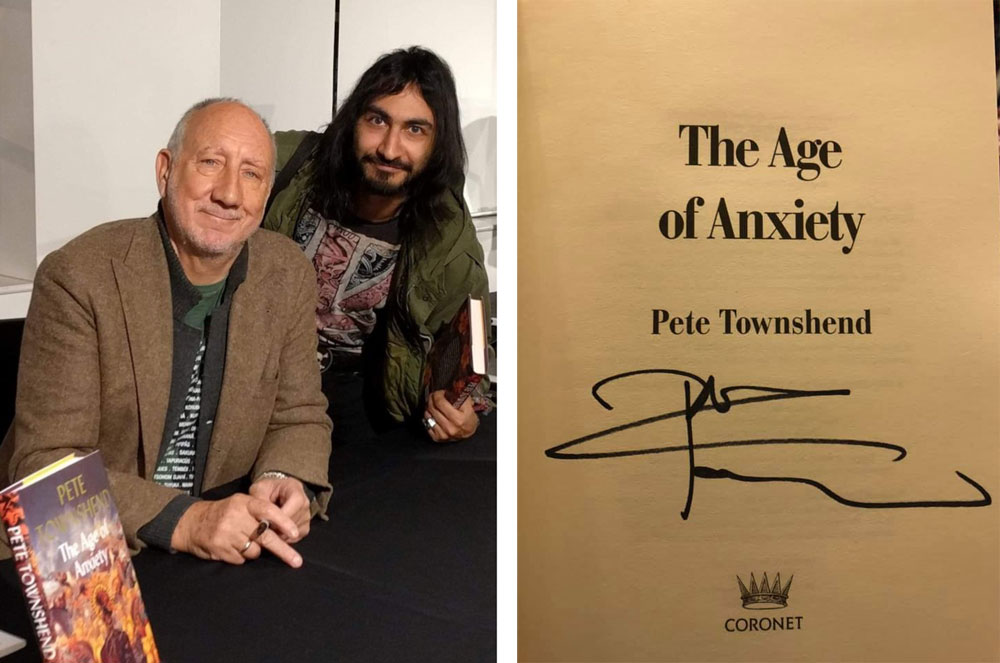

When the book was released last November, Pete went on a promotional tour for it, appearing at book events around London and Brighton, and giving dozens of interviews to media outlets around the world. His discussions about the book were insightful and fascinating.

Check out our book event page to view photos and videos of Pete's book talks and signings!

The following are a collection of excerpts from the various interviews Pete did for The Age of Anxiety.

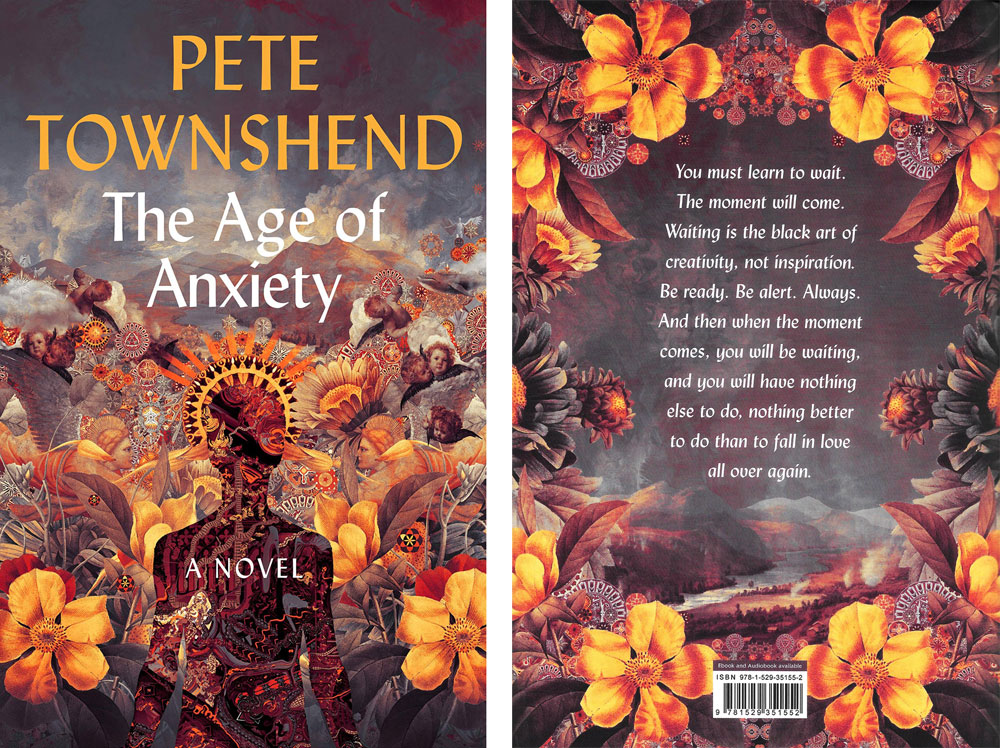

Front and back book cover. Artwork by Luis Toledo

Front and back book cover. Artwork by Luis Toledo

About the book

Pete Townshend Instagram post, June 26, 2019

This novel was written to provide the base for a solid libretto for an opera-art-installation I regard as perhaps my last major solo work. I started it in 2008, and some close fans are correct in thinking it grew out of other abandoned projects like THE BOY WHO HEARD MUSIC, and for a while was called FLOSS. I changed the title because the gravity of the subject seemed ill-served by a title (the name of the heroine) that for Americans in particular evoked dental floss. The libretto is complete. The music is composed. The video artists and installation artists are in position. I’m hoping 2021 and 2022 will see me get to realize this project at last.

Pete Townshend interview with Mariella Frostup, How To Academy, Westminster, November 6, 2019

When I started working on the project about 10 years ago, I decided I probably had one big new project in me. In other words, another Tommy, another Quadrophenia, or my lost project Lifehouse. Another big ambitious project. I felt it should be a romance, and I created this young musician called Walter. His girlfriend was called Florence, and he called her Floss for short. So the working title for years was Floss. When I started to plug the book to various people and talk about it, particularly to Americans who went “Ah Floss! Yeah, I get it, it’s about teeth!” So I had a conversation with Rachel my wife, and she said “Why not call it the Age of Anxiety?” I said it’s a lovely idea but unfortunately W.H. Auden, who I knew particularly from my work when I was an editor at Faber, was an English poet who had written a book [with that title]. Funnily enough it was an eclogue, a very long poem, about four people sitting at a bar in 1957 in New York; a soldier, a journalist, and a couple other people. And they are having conversations over a couple of weeks about the state of the world, and how difficult it was going to be for, I suppose, my generation to exist in the future. In other words, the whole poem is about the kind of concerns we have today. Which is we are not worried about ourselves, we’re worried about our children, and our children’s children. It was published in 1950, and I mentioned it to a few people, and nobody knew it, so I thought, “I’ll have that.” I love W.H. Auden. I love his poetry and I love him, so it gives me a chance to name check him.

Pete Townshend interview with Sam Leith, The Spectator, Book Club podcast, November 26, 2019

I didn’t come up with the title. My wife came up with the title. I had another working title and she came up with this title. I said to her, I can’t use it because Auden wrote this fabulous long poem called The Age of Anxiety. In fact Leonard Bernstein wrote a symphony or a song cycle based on it. I went back, and I got halfway through it — I’d read it before when I was younger — and I thought, “Actually, no, this is fine. I’m quite happy to bring the expression “the age of anxiety” into the present day and to own it. You know, I’m big enough a celebrity to transfer it into the modern world and for it to be an echo of what he started.

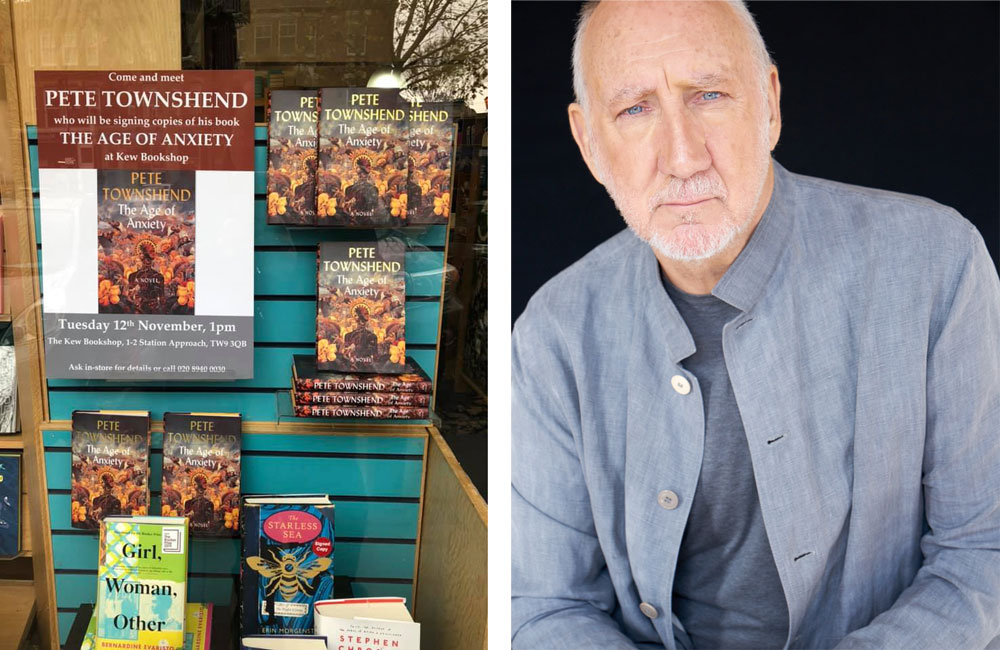

Window display at Kew Bookshop (credit: Gary and Melissa Hurley) and Pete's publicity shot (credit: Terry McGough)

Window display at Kew Bookshop (credit: Gary and Melissa Hurley) and Pete's publicity shot (credit: Terry McGough)

Drawing inspiration from the neighborhood

Pete Townshend interview with Steve Wright, BBC Radio 2, November 6, 2019

I was looking for a theme for a last major work. I’m pushing 75 now, I started this 10 years ago and I thought, “I don’t want to write another rock opera, I don’t want to do another Quadrophenia, I like movies, but I don’t like working on movies.” So I thought, “well what can I do?” And I thought that I’d like to do something that jacked into my neighborhood. So I looked around the neighborhood that I live in now, which happens to be Richmond-on-Thames, and I looked at what the people around me there were troubled by, and I could see that they were terribly, terribly anxious, and still are. And 10 years on it’s much worse.

Pete Townshend interview with Raina Douris, NPR, World Café, November 18, 2019

I thought, well as an older man, what do I do? I look at my neighborhood — and I live in what's probably a bit more like Brooklyn Heights than Harlem — and realize that even so, even though everybody was affluent and living well, they were still terrified. They were worried for their children, I think, worried for their future. And I thought "This is what I should write about." The whole issue of anxiety and mental illness, the issues about climate change and terrorism, polarization of political groups ... which is happening in Europe as well as in America.

Pete Townshend interview with Liz Kershaw, BBC Sounds, November 16, 2019

I think it’s a book that probably only I could have written, but I suppose any author can say that about what they’ve written. I think I drew on all the things that I know, but also a lot of the things that I found when I researched it. I started in 2008, and in 2009 I was a bit lost and I started to work out, “where does great music come from, particularly great pop and rock music, where does it come from?” And I decided it was from the neighborhood. The Who was Shepherds Bush and West London and the Beatles are from Liverpool, and it’s all about the neighborhood. So I thought, “I must go and investigate my neighborhood”, and I did so. This was in 2009 and 2010, and I was making notes, talking to people, talking to shopkeepers, talking to people in restaurants. And what I found was that once you went a little bit deeper than just daily chit chat, everybody was scared, everybody was anxious, everybody was frightened. They were frightened about climate change, they were frightened about ISIS, terrorism, the economy, everything. They were frightened about immigration, and they were becoming racists, some of them who otherwise you wouldn’t imagine would be. And it just seemed to me that something was bubbling, and I thought, ‘I’ve got a wonderful cauldron of stuff right here in my neighborhood.’ And guess where I live, I live in Richmond, which is pretty posh, but it’s the same all over.

Pete Townshend interview with Stephanie Bunbury, Sydney Morning Herald, November 1, 2019

As I started to open up as an artist, as a writer, as a musician – as someone hoping to write music that evoked, reflected and drew on what the people in my neighbourhood were thinking and feeling, it was clear that what needed celebrating wasn’t the sunny days by the River Thames, the lovely restaurants, the good schools, the four-wheel drives. What needed celebrating was what was in people’s heads, which was abject terror. I just wanted to start this book with anything goes, you know, but also then to really look at what happens, having lived through some very dark times.

Pete Townshend interview with Isobel James, Express, November 2, 2019

It's about, for example, that thing that we have when we're at a certain point in our life, when we think I'll just get a little cottage by the sea and I'll go and live a simple life, walk the dog on the beach and meet mates in the pub in the evening. Then you watch Chernobyl on the TV and you realise it can come from the sky - and it did come from the sky, and you can't insulate yourself from it.

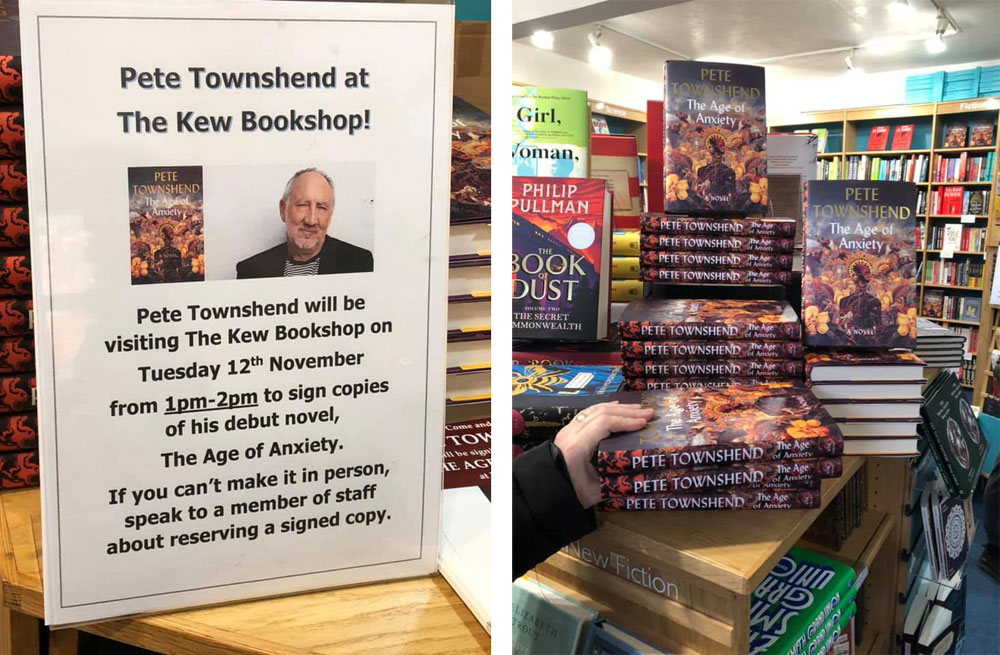

Book displays at Kew Bookshop. Credit: Gary and Melissa Hurley

Book displays at Kew Bookshop. Credit: Gary and Melissa Hurley

About the story

Pete Townshend interview with Eleri Sion, BBC Sounds Wales, November 21, 2019

The book is about a young musician who works in London and lives in Sheen, just outside Richmond. He’s a psychic fellow, and he starts to hear the anxieties, the fears, the phobias, and the troubles of the people who come to see him perform to forget all that. He hears that and he writes it down. And that becomes the fulcrum, the centerpiece of this book.

I started this book with these descriptions, this is something the young musician hears when he tries to jack in to what he is sensing is tremendous anxiety from his audience and in the people around him in his neighborhood. As he starts to walk around he starts to realize he’s got this psychic ability to hear what people are feeling and what’s troubling them. But just in a superficial sense. So he kind of aggregates it in his mind, and it turns into a kind of, not just music, but sound. So I decided to write between 15 and 20 short essays of descriptions of what this young man was hearing. And that’s how the story began.

Pete Townshend interview with Keith Cameron, Mojo, November, 2019

[The story is about] art and madness and inspiration, the psychic nature of being a creative artist, opening yourself up to an audience.

Pete Townshend interview with Sam Leith, The Spectator, Book Club podcast, November 26, 2019

At the heart of the story is music, is sound, is the music business. There’s a bunch of musicians and a bunch of painters and artists and the widow of an artist (the old guy eventually dies) and, of course, a concert at the end. I always like to have a concert at the end of my stories. The concert’s also really significant because there are very few concerts that I have done that I have walked off the stage and said ‘Oh my god, that was an absolute disaster!’ This is that concert. This concert is a disaster. Walters concert is a disaster. And it’s a disaster because what’s happened is that Walters father realizes his music and they perform it. I don’t think I’m giving anything away, there are so many strands and intertwining stories. But certainly the significance of music in the story is really important. This is my currency; this is my language; this is what I know best of all. I know how it works, how it affects people, I know how it affects people even when it fails.

Pete Townshend interview with Andy Greene, Rolling Stone, November 14, 2019

I didn’t particularly want to write a book about music. I didn’t want to write a book about where the tagline would be, ‘Pete Townshend’s new book — sex, drugs and rock & roll.’ They would have said that if I had written a book about fucking landscape gardening. ‘Sex and drugs and landscape gardening!' But in fact the book is about music and it is about sex. There are people in this book that actually have sex. Now isn’t that bizarre? And it’s about rock & roll. So, hey, sex and rock & roll? Where are the drugs? The drugs are there too! Because, lets face it, everyone in the world has sex. Everyone knows what rock & roll is. And everybody takes drugs. Everybody! There are no exceptions, though there might be a few Buddhist priests that don’t.

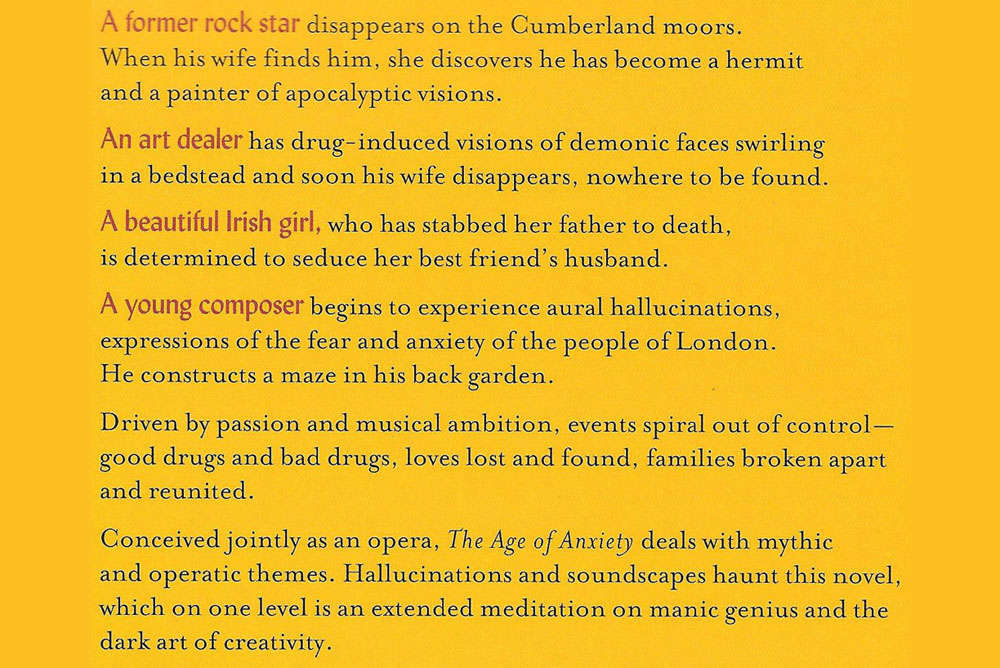

Story description on back cover of audio book.

Story description on back cover of audio book.

Outsider Art

Pete Townshend interview with Mariella Frostup, How To Academy, Westminster, November 6, 2019

I have come across Outsider Art recently. There’s a guy in Richmond called Henry Boxer who is involved with the Museum of Everything. He puts on exhibitions as well, and there’s one on at the moment at the Orleans Gallery in Twickenham which has one of my paintings that I own by Donald Pass. Donald Pass was John Lennon’s art teacher. He had this apocalyptic vision. He saw a huge angel in the sky gathering lots and lots of lost souls in front of him. I met him just a couple of years before he died, and I got to know his wife. It was all he ever painted after that. He had this vision, and he painted this apocalyptic vision over and over again. And so I started looking at Outsider Art. I decided that the art of the so called “Mad” was really, it was a safe way to describe that every artist has their own approach, their own narrow alley way down which they operate. I suppose I got sick of the alley way that I’ve been in since I was 16 or 17 which was that you guys are important, and I’m not. That was the madness that I had. Sorry, but that was what happened to me.

Pete Townshend interview with Sam Leith, The Spectator, Book Club podcast, November 26, 2019

I think that artists definitely see things in a different way. It’s important to know that the narrator is an art dealer who deals with Outsider artists, and Outsider artists definitely see things differently to normal people. You can see it in their work. So I think that the notion that a young man, who has had quite a normal upbringing, should suddenly in the middle of a concert at somewhere like Dingwalls playing an old R&B song, suddenly jack into something that is immensely psychic is cerebral and strange and fantastical. You could say “drug induced”; you could say “alcohol induced”, but that’s not my inference. My inference is that this is somebody who’s trying to push their creative envelope a bit further, a bit further and a bit further and then finds, actually, “Bang!” Suddenly they’re working in another arena: another manner. And I think really inspired writing — and Gabriel Garcia Marquez is probably a good example but there are many — of people who have, in a sense, tried to write and open up their consciousness. They aren’t necessarily describing the visions that they have, but they’re describing the visions that they believe they might have if they break through. That’s in a sense what I suppose I’ve done.

"The Vision" by Donald Pass - from the private collection of Pete Townshend

"The Vision" by Donald Pass - from the private collection of Pete Townshend

The Narrator Louis Doxtader

Pete Townshend interview with Steve Wright, BBC Radio 2, November 6, 2019

[The narrator Louis Doxtader] is an art dealer. He deals in Outsider art, which is the art of the mad, the art of the over stimulated. That’s what he’s done all his life. He is based on somebody that I know, so the background is authentic. He was the first person I had to show the book. The narrator has got a bit of a life history. He’s the godfather to the central character, who’s a young musician called Walter, who’s in a kind of R&B club band. And he starts to hear the anxiety of the audience that come to get away from their troubles. He starts to hear, in a sense, what they’re trying to get away from. It’s not existential. It’s carefully plotted. It’s got characters I think that you can get your head around. Some of them are based on people that I know.

Pete Townshend interview with Liz Kershaw, BBC Sounds, November 16, 2019

[The narrator] is based on a friend of mine who’s an art dealer, a guy called Henry Boxer. But he could be any art dealer whose life has fallen apart.

Pete Townshend interview with Japanese TV, November 15, 2019

This is my first novel. I had to be absolutely certain that I was in familiar territory. For example, I speak a little bit about horses, but that’s because at the house I have in the country I lease some of my land to a woman who breeds horses. So I had experience at that. But equally with respect to the art dealer, I know an art dealer who lives just down the road from me who actually deals in Outsider Art. I said, “Do you mind if I base my narrator on you?” and he said “No, sure. It will help sell some paintings!”

Pete Townshend interview with Raina Douris, NPR, World Café, November 18, 2019

The narrator is the godfather of a young musician. He’s not a musician himself, he’s an art dealer. I wanted to have a reason for him to write the book. I wanted him to be an isolated, lonely voice, somebody who had married, lost his wife and was often in the company of younger people. Why would I do that? Well, it's where I am. I'm in the music business, coming up to 75 years old, and I'm surrounded by young people. So I'm familiar with that world; I'm familiar with the machinery of it. I'm a man in my 70s who occasionally gets asked on a date by a younger woman. So I’m kind of used to that. (laughs) I’m married now again, so I’ve had my little burst of freedom. I’m familiar with the language in a sense.

Pete Townshend interview with Japanese TV, November 15, 2019

The only person who I think takes drugs in the story is the narrator. His story is that he’s a recovering heroin addict. He’s an art dealer. That’s how he makes his money. He deals with what we call Outsider Artists, people who produce Art Brut in the French tradition. He can see and understand how people who paint, who write, who make sculptures, who make music. Who have visions, who see things differently to us, for example can’t speak very well but they can paint beautifully. Who might be autistic, or might be damaged mentally in some way, but can still produce great art. He wants to be able to integrate with them. I wanted him to be able to integrate with them.

Pete Townshend interview with Nick Craven, The Mail on Sunday, October 27, 2019

Drugs are a necessary part of the survival of our current species and I wanted my hero to be a man of incredible conscience and sturdiness. Louis is the moral centre of the story, unreliable at times but generous and capable of helping those in need. Despite his addiction, I wanted my narrator to be someone who had resorted to drugs as a medicine, in a sense, and at the same time managed to do a good job of bringing up his daughter. That’s a story I see around me with all of my famous friends, most of the people I know in the music business who are pilloried for their bad behaviour. There are very few exceptions. The best example would be Keith Richards, who is on Instagram now with three or four beautiful children, who all seem to worship him. So what’s wrong? What is the position we’re supposed to take? “Ah, Keith Richards had a clean supply of heroin, so it was no problem for him?” If you live on a council estate, the chances are you don’t get a clean supply of heroin. That’s the problem. I’m not arguing for the legalisation of heroin, but I do think we’re not getting it right, the way that we view the issue. So I wasn’t making any point with my narrator but I wanted him to be both dirty and clean.

Pete Townshend interview with Raina Douris, NPR, World Café, November 18, 2019

The narrator is accused by somebody that's close to him of the possibility that he has raped somebody. I started this book in 2008, before the #MeToo movement kicked off. He’s not a celebrity himself, he’s just an art dealer. Whether or not this accusation is true or not is left to the reader to decide. In a sense, it does jack into the current #MeToo movement, but it was never meant to. I didn't mean it to. I certainly don't expect to be accused of anything like that myself.

Pete Townshend interview with Andy Greene, Rolling Stone, November 14, 2019

This isn’t about celebrities or powerful men having sex with younger women. It’s about rape, at least that’s one of the strands, and the insinuation of rape. It’s about the possibility of it when people are at a wedding, they take drugs, they get smashed and they have sex. Who is responsible if both people are smashed?

Pete Townshend interview with Nick Craven, The Mail on Sunday, October 27, 2019

I’m not talking in the book about something I have experienced. I don’t think I’ve ever even been close to being accused of rape. I had enough sex. I lived a wild enough life, but… touch wood… you can never tell. I drank a lot. I didn’t black out. If, like some drinkers I know, I had blacked out every night, I couldn’t put my hand on my heart and say no. I can remember everything about my life, so I’m pretty sure that I’m not going to get accused of rape.

Pete Townshend interview with Chris Charlesworth, Waterstones Books, Brighton, November 07, 2019

Some young people at the wedding are plied with drugs by the narrator. And the narrator is the key drug man, the guy that knocks out the drugs. His history is he is an ex-heroin addict. I wanted him to tell the story because he had been accused of something, and he felt that if he could tell the story and explain what was going on throughout the story that he would be able to expiate his guilt.

Chris Charlesworth and Pete Townshend at Brighton book event. Credit: Derick Bhupsingh

Chris Charlesworth and Pete Townshend at Brighton book event. Credit: Derick Bhupsingh

Walter

Pete Townshend interview with Gordon Smart, Radio X, November 8, 2019

I think in a sense, I share the same anxiety as the hero of my book, who’s a young musician called Walter. He’s in a band, he’s listening out for what his audience want songs about. What he starts to hear, he’s a bit psychic, he starts to hear that they are all anxious. They are all worried. Even though they are all out on the town at Dingwalls, getting drunk, doing a few lines, and having a night out. Below the surface they’re really deeply concerned. The story is about how that effects him as a young musician. And a young man. He’s married, and it breaks up his marriage. It means he leaves the group. He can’t function. And it requires a lot of help for him to get back on track.

Pete Townshend interview with Raina Douris, NPR, World Café, November 18, 2019

The way that the narrator tells the story, he’s really trying to tell the story of a very wholesome couple of people. There is the young musician [Walter] who is his godson, who has a kind of psychic connection with his audience, which in a sense allows him to jack into their anxieties. It disables his work so he leaves his career behind and meets a young woman who is an equestrian, she runs a stud. And these two stories were loosely based on people that I know.

I think what happens [to Walter] is he was disabled by something. I think many of us have epiphanies in our life. We have moments when everything changes for us, and I think this is what happens to him. He’s very happy in his job, he’s got a lovely wife, a beautiful Irish girl who works in radio. And she thinks he’s a clever guy and she’s hoping that he will become a poet. They have a good life together. He’s in this great little R&B band that play at Dingwalls, and they have a solid audience, and he loves it. He’s a singer, but also a harmonica player, and his harmonica playing is his big thing which he is extremely good at. Suddenly, he realizes that this group of middle aged women in the front row are actually there to forget their troubles, that’s why they have come to see this band. What actually happens is he hears what they are there to forget, to leave behind.

Pete Townshend with Joe Penhall at Foyles book event. Credit: Mike Baess

Pete Townshend with Joe Penhall at Foyles book event. Credit: Mike Baess

Paul Jackson

Pete Townshend interview with Liz Kershaw, BBC Sounds, November 16, 2019

[Paul Jackson] is a composite of many different people. Robert Plant maybe, Roger Daltrey, people like that. But also some of the more bombastic figures. It could be anybody that’s been in a big prog rock band, some of whom of course are gone now.

Pete Townshend interview with CBC radio, November 6, 2019

This older guy [Paul Jackson] has been a big artist in a big prog rock band and he decides he wants to be in a movie. And he gets to the end of the movie and he realizes that he just wants to quit. And he does, he quits and he starts to draw. And he draws really strange apocalyptic paintings. His agent is a dealer in Outsider Art. He’s the narrator of the whole story. He is called Louis, and he’s a dealer in paintings of the mad. He is also the godfather of Walter. And he puts these two guys together. And then it was up to me to sort of put myself inside the older guy and say “what would he say to the younger guy?” And I think what I would say many, many times to young musicians who have a kind of black period, a period of being shut down and unable to write or to work or even to contemplate that possibility, is just wait. Just wait and be ready, because the moment will come. This is something I do believe, and I’ve had to learn to do that. People talk about inspiration like it’s some magic thing that comes out of the sky just when you snap your fingers. You know, “If I go to the right lake and I meditate, I will automatically be inspired.” No you won’t. I think a lot of this is about stuff we really don’t understand.

Pete Townshend interview with Raina Douris, NPR, World Café, November 18, 2019

I used a couple of connections [to Tommy], the hang glider scene at the opening is like the end of Ken Russell’s film of Tommy. I wanted to create a visual clue to the fact that the old rock star is somebody like a mixture of artists from the late 60’s early 70’s, what we call “progressive” rock artists. I'm less conscious of my young hero, Walter, being similar to Tommy in any way.

Pete Townshend interview with Mariella Frostup, How To Academy, Westminster, November 6, 2019

I asked Roger if it was possible to use the very first song that I wrote, which was called Hero Ground Zero. It’s the song that Paul Jackson sings when he decides he’s lost his marbles as it were. He feels that he’s disowned. He feels that he’s been let down in a sense. He feels that he’s lost his connection with his work, with his life and who he is. Roger agreed that I could use that on a Who album, because I knew that the Who album would come out long before this book. That was the intention. But I also wanted a bridge.

Pete Townshend chats with Mariella Frostup at Westminster book event. Credit: Karen Geary

Pete Townshend chats with Mariella Frostup at Westminster book event. Credit: Karen Geary

Female characters

Pete Townshend interview with Mariella Frostup, How To Academy, Westminster, November 6, 2019

When I was looking at the female characters I thought I had to make them really strong and real. So I started to base them on women that I had known and found interesting. Or that I found were nuts, which was interesting because they were eccentric. My editor encouraged me to write more and more dialog, but I hadn’t written much dialog because I didn’t think I was much good at it. So I thought I won’t write it, I’ll just describe conversations. In the end he encouraged me to make my characters talk. As soon as they started to talk, they started to walk away from me, and I had to keep bringing them back. As you start to put words in the mouth of your characters they become real. But they also become characters that you can’t control anymore. The woman in the story here, the youngest and the maddest and the sexiest, ends up taking the book over at the end. She just sort of says “No, I don’t like the way you ended it, I’m going to end it!”

Pete Townshend interview with Sam Leith, The Spectator, Book Club podcast, November 26, 2019

I wanted to create female characters that were really solid and authentic. And so what actually happened was I based them on people I knew. And hey guess what, all women are fabulous. A couple of them that I picked, I didn’t see them as fabulous until I wrote them down, and then I thought, actually they are incredibly strong characters. I think if you write any good character strongly, and want to serve them properly, they become enticing. So I just wanted the women to be real. I’ve been brought up in the world of rock and roll, and a lot of the women around the industry are very glamorous and powerful. In a way, I’m glad that in the end, I didn’t mean to give the book to one of the female characters, but she has the last word.

Pete Townshend interview with Andy Greene, Rolling Stone, November 14, 2019

I wanted to write a book where the female characters were as strong as the men. I also wanted them to be really authentic. One of the things that happened is that the women in my mind, the women in my life and the models I used for the female characters, they are much, much stronger than the men. My first wife Karen, for example, is an incredibly strong person. One of the reasons our relationship broke down after a long, long marriage, over 25 years, is because I was the weak one, not her.

Pete Townshend interview with Nick Craven, The Mail on Sunday, October 27, 2019

People have evolved. Katie Lane, who was married to Ronnie Lane, is very beautiful, very hypnotic, unquestionably somebody who believed in angels and psychic phenomena. She doesn’t seem to dabble with that quite so much as she used to, but there was always a sense that she knew what was going to happen before anybody else did. I folded all of this stuff in to the story knowing I would get it right.

Pete Townshend interview with Stephanie Bunbury, Sydney Morning Herald, November 1, 2019

I started to look, not at groupies, but some girlfriends I’d had in days when I was free or made myself free, women I admired or for various reasons, was perhaps intimidated by or amused by and created these female characters, to the point now where I’m kind of in love with all of them. It’s a very weird feeling. [Selena] is the maddest. I love the fact that Selena makes stuff up and gets away with it. If there is anybody in there I’d like to f---, it’s definitely Selena.

Pete Townshend interview with Liz Kershaw, BBC Sounds, November 16, 2019

I wanted the female characters that I created to be really believable. I think I’ve tried to create female characters before and found it really, really hard. I think it was because throughout The Who’s career, I’ve been speaking to a predominantly male audience all my life. We started in West London as a mod band, and the mods were predominantly boys, and so we served that audience. And I think served them very, very well. But I haven’t really branched out that much. I decided to base the characters on real people, and [Siobhan and Selena] is a real couple that I know.

Pete Townshend interview with CBC radio, November 6, 2019

The book was meant to be rock solid to create a really good platform for what happens next. And in so writing it, I kind of fell in love with all the characters I created. There’s one character, a female character, at the end of the book I was so enamoured with this female character that I created that I gave the whole book to her. I gave her the last word.

Finding Pete in the characters

Pete Townshend interview with Mariella Frostup, How To Academy, Westminster, November 6, 2019

The thing for me when I came to this book was that I didn’t want to keep myself out of it. In fact, what I wanted to do was ground it like it’s rock solid. In so doing I needed to make sure all of the characters, all of the settings, were things that I had known and experienced. So the fact that the two principles are people that have had apocalyptic visions, a lot of people here will know if they read my biography or heard me talk ever will know that as a little boy I could hear music up until the age of 11, and then it stopped. I used to sit and hear music, the most amazing music, and I’ll never be able to hear music as wonderful, because it was coming from my own brain and I was making it up, and it was gorgeous. A bit orchestral music, also slightly electronic kind of music, which is kind of abstract music. So that’s something that I experienced, so I wanted to write about that. The fact that the old rock star is an old rock star and he makes a movie, that he finds making the movie very hard, that’s drawn directly from my experience from working on the music from Ken Russell’s Tommy. And when I finished from after 6 months working for him, I took him aside and said “I will never, ever, ever work on a movie, ever again!”

Pete Townshend interview with Shilpa Ganatra, The Irish Times, November 9, 2019

As a celebrity author, people are going to be wanting to find me in it. But no, the thesis that I wanted to pitch was not autobiographical. The thesis is, whether you’re a writer, artist, dancer, musician, film-maker, do we have to open ourselves up in some way psychically or intellectually to the needs of our prospective audience? Who are we working for?

Pete Townshend interview with Stephanie Bunbury, Sydney Morning Herald, November 1, 2019

Being a face, being a celebrity. People will be looking for you. I don’t necessarily feel that I’m in any of them. What is clear is that they all speak with my voice.

Pete Townshend interview with Steve Wright, BBC Radio 2, November 6, 2019

I hope people don’t dig into this kind of looking for me. They might find shades of me. They might even find shades of people I might know. And I would never disown the history that I’ve had with The Who. But the challenge for me was to do something that only I could do.

Pete Townshend interview with Raina Douris, NPR, World Café, November 18, 2019

I really wanted to write a proper fiction novel, at last. I was warned by my editor that if I went too far into general fiction, people would lose "me." I am a celebrity; I am known for what I do in a rock band, so with this book, I tried to stay in familiar territory. I'm not taunting people to try and find me in this. If they try and find me in this — they might, they might not, but I don't think I'm really there.

Pete Townshend Instagram post, June 26, 2019

My publisher is flagging this as a ‘rock novel’. The author is a rock musician, and there are some characters who are in bands, but it is also a mystery story, and a story about drug abuse, being a parent, creativity, anxiety, being blocked as an artist, and the psychic miracles worked by certain women in the story. Believe it or not (and I doubt you will) this is not autobiographical. I’ve done that. But the story is set very much in my world. My work, my neighborhood, and is inspired by my people.

Pete Townshend interview with Isobel James, Express, November 2, 2019

This is actually a great rock novel. Yes it has been written by me and I come from that world but what actually happened when I wrote it was that I didn't want to touch on the obvious. When I wrote my autobiography, I was as honest as I possibly could be. I've told my story and I've made my apologies if I need to make them.

Pete Townshend interview with Jonesy and Amanda, WSFM, November 18, 2019

They are all characters that are based on people that I know, but there’s no real connection with me other than that. I wanted to make sure my characters were authentic, so I stuck pretty close to the rock industry and to the art world which, of course I was an art school boy and have always been pretty closely associated with that. Always been a bit of an arty bugger. So in a sense drawing a line back, all the way back to when I was at art school and I was looking ahead at doing ambitious, kind of arty things, and then The Who came along and wrecked it all. (laughs)

Pete Townshend interview with Stephanie Bunbury, Sydney Morning Herald, November 1, 2019

I think mainly [what spurred me on was] the feeling that probably I could do it and if I could do it, then I should. It’s a bit like someone of my age deciding to run the marathon.

Pete poses for photographers at Waterstones Picadilly. Credit: Karen Geary

Pete poses for photographers at Waterstones Picadilly. Credit: Karen Geary

The writing process

Pete Townshend interview with Raina Douris, NPR, World Café, November 18, 2019

I suppose what I was doing was trying to create an interwoven, flowing plot that had more than one strand. This is my first novel and it's the first time I've tried to properly plot something. I must quickly say that, in music, we try not to do that. We try not to plot things, we try not to create twists, we try not to close the story for you. What good popular music does is allow you, as the listener, to draw the conclusion and write the ending.

Pete Townshend interview with Andy Greene, Rolling Stone, November 14, 2019

I didn’t have a desire to write fiction. I wanted something that would allow me to go off in a number of different directions. It’s a multi-stranded story that touches on a number of different things which I feel will help me to produce interesting projects that rise out of it.

Pete Townshend interview with Sam Leith, The Spectator, Book Club podcast, November 26, 2019

I wanted to write a story that was a page-turner. So I wanted it to be plotted with twists because that always engages me. I read a lot of thrillers and crime and John le Carré and stuff like that and Olen Steinhauer, who’s the modern equivalent of le Carré. And it’s the twists that get me through to the end of the book. But I also wanted it to be absolutely authentic: I wanted it to be something that you would believe might be possible and be real.

What I did with this first was constructed a plot. I went to a plot website. Oh, there are many plot websites. I decided on the Aristotelian plot and it means that you have to have a building story, developing characters, then it comes to crescendo and then a gentle epilogue and then a conclusion and, possibly, a closing line. So I had that: I had a scheme — a picture — of the story before I started to write it. And I really enjoyed writing it. I wrote it very quickly: it took me about three months and I was writing between three or four and ten pages a day. I was just writing in a kind of tight bubble. I wanted to draw together suddenly, at the end — almost in one song — so that all of the different stories would suddenly resolve in one moment at the end in the concert. I think coincidence is an interesting way of describing what often happens cosmically when things do coagulate like this.

Pete Townshend interview with CBC radio, November 6, 2019

I was an editor at a publishing house for a long time, and I worked with a lot of fiction writers and I understand how fiction works. But I’ve never tried it myself. But it came very naturally. I had a wonderful editor, a guy called Mark Booth, his imprint is part of the Hachette company. He guided me through, and we fixed a few things that weren’t quite right. It’s been great. It’s been a great learning process for me as well. I’m really pleased to the response to it so far. It’s been so positive. I’ve been doing signings and people who have read the book really love it, so that’s cool for me.

Pete Townshend interview with Eleri Sion, BBC Sounds Wales, November 21, 2019

I kind of roughly sketched out the plot, which I knew would work. I knew it would guide me so I had a good ending. But then I didn’t let my characters speak. I just wrote it as a story, a prose play. When I started working with my editor, Mark Booth, he said ‘Why don’t these guys talk?’ So I said ‘OK, I’ll give it a try. I don’t think I’m gonna be very good at it, but I’ll give it a try’. And as soon as I let my characters talk, they started to talk to me! (laughs) The characters come to life in front of you. And they kind of get up to mischief. They start to go off on their own adventures.

I love to write. I love writing songs and being in my studio. So this for me, sitting and writing and spending 3 months, which is how long it took me writing this novel, I just loved it. I did indeed, as the narrator does in the story, I sat in a little room at the top of a house that my wife owns in the South of France overlooking the sea in the very distant distance, and knocked it off. And then whipped it into shape with my editor, Mark Booth, who really did help me make it make more sense.

Scrivener is a program that helps you organize your thoughts. It’s meant to have a multi-functional aspect. One of the first things that I did with the book was describe my characters in a special area of Scrivener, where they came from, what they looked like, when their birthdays were, that kind of thing. So when I was writing the story, I could just literally move over to that section. I think it’s a brilliant piece of software. It’s very basic, but I think for creative writing it’s fabulous. But also for brainstorming.

Pete Townshend interview with Sam Leith, The Spectator, Book Club podcast, November 26, 2019

I write pages and pages and pages every day in all different kinds of things: essays and diaries and mind farts and… I’ve got one project called Aimlessness and, every day, I try to contribute to it. And it’s some of my best writing. So I’m writing all the time.

Pete Townshend interview with Michael Lello, New York Post, August 28, 2019

I write all the time, it’s a need, a necessity. I have no strong feelings about it. It feels as though writing – prose, poetry, letters, essays, diaries, therapeutic pages, lyrics, plans, experiments, Instagram posts, emails and even shopping lists – is who I am 90% of the time. Music is huge for me too, but that either flows or it doesn’t. The novel now exists, and it is indeed like a shopping list: What happens now? I have one project in my Scrivener app which is called “Aimlessness.” That is developing nicely. I have some vague ideas for a sequel to “The Age of Anxiety.” I will keep myself busy.

Pete Townshend signs books at Waterstones Picadilly. Credit: Gary and Melissa Hurley

Pete Townshend signs books at Waterstones Picadilly. Credit: Gary and Melissa Hurley

Future projects

Pete Townshend interview with Steve Wright, BBC Radio 2, November 6, 2019

The book’s a story, it’s a fictional story, but it’s rooted in things I’m interested in as a songwriter, as a composer, as a musician, as a mentor to other artists. If I had stayed at art school before joining the ‘orrible Who, this project is the one that I think I would have done. I think it will end up with an art installation of some sort. But it’s what I’ve always wanted to do; to create something that has a story, has an integral kind of reason for being, and then has a place where people can interface and interject their own ideas and their own music. I wrote a book primarily to make sure that if I wrote a libretto, and songs, and other music, and commissioned other music, that it would make sense. That people can carry the book, have read the story, and know something about what it is that I’m aiming at.

Pete Townshend interview with Mariella Frostup, How To Academy, Westminster, November 6, 2019

The reason why I wanted the book to be a really rock solid story was because I was unsure about the way that I might be able to realize an art school vision. I was at art school from 1961 to 1964, and in the last year of art school I slowly but surely stopped going to college because we were doing gigs and I was making money. At that time I did this most extraordinary art school course and I had this idea of creating kinetic sculpture in which there would be music, light, video, which didn’t exist, but television images and stuff like that, and film. And then I stopped and ended up playing guitar with a bunch of yobbos in a band called The Who. So I’ve always wanted to close that circle. And so I thought, if I do close that circle then I need something that will root me and ground me. So that’s why it’s a plotted novel. But the facets of it are interesting too, because they allow me to pursue in a sense the natural path, the easiest path, to let the water roll down stream. So I’m thinking maybe now to start with doing a reading of the libretto, which I’ve written a libretto in iambic pentameter, like Shakespeare. In other words, it’s poetic, but there are song lyrics as well. I’ve finished all the music, and I’ve recorded all the soundscapes that are in the story. All of the music that the young man hears has been recorded. That’s all done. But I think the next step might be for me to just read it, and have music play in between the reading.

Pete Townshend interview with Sam Leith, The Spectator, November 30, 2019

I wanted something that was rock solid so that I could work on it in an evolutionary way, an unfolding way. I should probably never have used the word “opera” because I don’t know whether this will be an opera: it may be a song cycle; it may be a reading like Under Milk Wood. I don’t know. But I’ve written a libretto, based on the book, which was fantastic, because I knew the book by heart and so I just wrote this verse. And so the book had a function. When you write a novel, what you don’t expect is the story and characters are going to take on a life of their own. And in the end they write themselves.

What I wanted was to write something mythic, deep, and multi-layered. But also had a really solid plot. So then I challenged myself to write an opera, and this is the result. This may well remain between the pages, but what I’m hoping is this will take off and lead me to other things.

Pete Townshend interview with Andy Greene, Rolling Stone, November 14, 2019

I think I might do it as a one-man show. I’ve been experimenting with a reading and I’ve been creating a libretto. I wouldn’t read the whole book. It would take weeks. But I’ve created a libretto out of the novel. Maybe there would be an orchestra that performs the music that Walter hears.

Pete Townshend interview with Sam Leith, The Spectator, Book Club podcast, November 26, 2019

In the book there are descriptions of almost apocalyptic scenarios. But some of them are just a chaotic vision. For example, one is the description of birds singing, birds dying, ducks quacking, and that was rooted in a couple of conversations that I had with people who were just worried about where have the sparrows gone. Why don’t we have sparrows in London anymore? It was that anxiety. So I have about 15 soundscapes. This is the stuff of this story: this is the guts of it: this is the backbone of it, which is this young musician develops out of the blue… he starts to hear the anxieties, the fears, the distractions, the tension, swilling around in the audience that he’s playing in. And it distracts him so much that it disables him as an artist. He can’t continue to work. He’s encouraged by his godfather, who’s the narrator of the book, to write down what he hears. And he does that. So I have those soundscapes, and that’s where the whole thing started, with those essays. What was I going to do then? I was going to realize them as electronic music, possibly as orchestral music, might write it myself, might commission somebody else to do it. Have a few songs written to go in between the soundscapes. And then I realized actually what I really want to make sure is that at some point that people understand, the whole point of this is not just to tell a story about a young man who is psychic, but the fact that he hears what’s going on in the audience is what’s important.

I do think the most important thing next for this is music. Will I be able to perform music or commission music. The first thing that I wanted to do with this was to make the music of the soundscapes, the stuff that Walter hears. I wanted to do it electronically, with electronic music. I’ve worked with electronic music since 1971, and I’m very adept at it, I’m skilled at it. However, not enough to actually make this work. I couldn’t do it. I’ve fiddled around with my synthesisers in my big studio, I’ve made lots of funny noises, I thought this isn’t as good as the words! The words are better. In the end, I gave the commission to a young composer who actually turned these soundscapes into music. In the story, it’s the young musicians father who does this for him. He takes his essays and turns them into this most fabulous music. But I want to take it further. I want to go back and look again. There are other chapters, and other shades. This is just me as a composer. It’s kind of a little bit wacky. What I do is really fun. I love spending time in my studio, and I love writing. I’m excited about what happens next. I don’t think that it feels to me like I’m being hard on myself, but it is challenging. This was an incredibly fulfilling challenge, a tailor made challenge.

Pete Townshend interview with Stephanie Bunbury, Sydney Morning Herald, November 1, 2019

I tried to do [the soundscapes] myself first, with a mixture of electronic music and orchestral composing. I did quite well but then I thought, ‘Hold on, what I really want is that ... this piece live on.' I want it to be something that is performed as a piece of music and therefore it needs to be orchestrated. [Composer and organist James Morgan] made the brief happen. What he’s done is sensational, scary, frightening and wonderful.

Pete Townshend interview with Shilpa Ganatra, The Irish Times, November 9, 2019

I’d seen The Age of Anxiety as a magnum opus: a big piece that might be the last thing that I do, just because of its sheer scale. But I don’t intend to stop writing music or doing solo projects. It’s just been overwhelming. I started it in 2008, I’ve done several experiments. I was once hoping that I could do the entire thing on a piano, then using electronic music. Then I realised that it would be better if I stuck to what I know, which is rock music, but it wasn’t flexible enough. Then I tried it with an orchestra with James Morgan, and of course, an orchestra is fantastic.

Pete Townshend interview with Liz Kershaw, BBC Sounds, November 16, 2019

I’ve recorded all the music, done all the songs, I’ve commissioned orchestral music for the soundscapes, in other words for what the young man hears in his head, that his dad composes music for. His dad’s a classical musician, he composes this fabulous music. I’ve composed all the music, done all the storytelling using operatic recitative. And I listened to it when I got back off tour a couple of days ago, and I thought ‘There are several other ways I could do this.’ So I haven’t exactly decided how to do it yet. But one thing I am certain of is I want there to be some sort of interactive event. And I think the best way to describe that is an art installation. In other words, a place where you go to see and hear and be a part of the dialog and the conversation that the music and the book and the story and what we all have to say to each other, about the way we feel today, in an open forum. And also internationally hopefully. In other words I hope that now that translation is better working now, we could have a conversation for example with people in India and China.

Pete Townshend interview with Eleri Sion, BBC Sounds Wales, November 21, 2019

The film rights have already been sold to Sony / Columbia / Screen Gems. So quite what they do with that I don’t know. My role would be to make it come to life on the stage and in the art gallery. And it works very, very well when I just read it out. Then, what I have ready now, it’s all recorded, is all of what I call the soundscapes. All of the music which the young man who hears the anxiety of the people around him, I have all that all ready to go. So the first step may be a reading with music, and then after that we’ll see what happens. I very much hope I’ll get a record out, because I’ve written about 25 songs which are a part of it. It’s quite long, and probably needs shortening, but it’s all ready to do whatever happens next. All I really need is some time.

Pete Townshend interview with Nick Craven, The Mail on Sunday, October 27, 2019

The movie rights to The Age Of Anxiety have already been sold. I’m asking myself questions every day. Do I want to be in it? Do I want to let Roger [Daltrey] have it? He would be fantastic in the role of the old guy. I want there to be an art installation too. I’ve been talking to a couple of people that work with Kanye West and P Diddy in New York. Young Jewish artists, in their early 20s. Brooklyn-based. They’re very smart. They’re into technology, image projection, artificial intelligence. I’m overwhelmed by the ideas they come back at me with, but every time they do, I think: “Oh my God, that’s going to cost as much as a Hollywood movie!” God knows [when we will see and hear all this]. It’s such an ambitious project, it’s so expensive, I’ve been paying for it by going on tour with The Who.

Pete Townshend interview with Keith Cameron, Mojo, November, 2019

The opera is quite a way off. This is going to be expensive. There’s lots of AI material. It feels to me like another Lifehouse, something that may or may not happen. And may indeed overwhelm me.

Pete Townshend at Foyles book signing event. Credit: Dan DiCarlo

Pete Townshend at Foyles book signing event. Credit: Dan DiCarlo