Pete Townshend’s solo album Empty Glass was released 40 years ago this month!

The album hit the stores in the UK on 14th April 1980, and in the US the following week on 21st April. It was released on Atco Records, which was part of Atlantic Records. It was Pete’s most successful solo album, reaching #5 on the Billboard charts.

Pete began writing the songs and recording demos for Empty Glass in his 24-track home studio around 1978. A couple songs ('Keep On Working' and 'Empty Glass') were initially recorded by The Who during the Who Are You sessions.

Recording sessions for the album began in November 1979 at Wessex Studios in North London, with legendary producer Chris Thomas at the helm, and Bill Price as the engineer. Additional recording was done at AIR Studios in Oxford Street and Pete’s Eel Pie Studios.

Pete performed all the guitar and synth parts, and brought in various musicians to lay down the piano, bass, drums, and harmonica parts. The lineup included Rabbit Bundrick on keyboards, Tony Butler on bass, Simon Phillips, Kenney Jones, Mark Brzezicki, and James Asher on drums, Peter Hope-Evans on harmonica, and Raphael Rudd, who arranged the horn parts on 'Rough Boys'.

In addition to the incredible instrumental work, Pete also gave a stunning vocal performance on Empty Glass, digging down deep to display a wide range of styles and heart-felt emotions throughout the album. His singing on songs like 'I Am An Animal' and 'Empty Glass' is absolutely beautiful.

Pete wrote and recorded Empty Glass at a tumultuous time in his career when he was moving away from The Who, following the death of Keith Moon in 1978. He was under contract to deliver albums for both The Who and as a solo artist, so Pete was writing material for both Empty Glass and The Who's Face Dances album at the same time. Many consider the songs chosen for Empty Glass to be far superior.

Pete was also experiencing difficulties in his personal life at that time, dealing with alcohol problems and marital issues. Many of the songs on the album are introspective, spiritual and deeply personal. Pete dedicated the album to his wife Karen.

At this period of his life, Pete drew on the strength and influence of Avatar Meher Baba. He included a quote from his master in the liner notes: ‘Desire for nothing except desirelessness, hope for nothing except to rise above all hopes, want nothing and you will have everything.’

Here is a close look back at this seminal album in Pete Townshend's vast career, as told primarily by Pete himself in various interviews and writings over the years.

Writing material for the solo album

Pete Townshend interview with Carl Arrington, Creem, November 1980

I tried to imagine that I was not writing for a solo album so I wouldn’t get into an isolating pattern of writing some things for me and some things for the Who. At the moment I recorded ‘Empty Glass’, I used the best material I had available. The same is true of the new Who album.

Pete Townshend interview with Charles Shaar Murray, NME, April 1980

The only distinction I made was that if I was really going to do a solo album deal properly – the only way I could do it would be to take the best of any material that I had at any particular time, rather than knock together solo projects of any sort based on material that the Who had rejected. So my album – though I was able to take a lot more risks with the material than the Who would – could have been a Who album if we’d happened to be recording at that time, just as the Who album that we’re doing now could have been a solo album. I just decided to write – to write straight from the hip and offer everything to the project that’s going at the time, not earmark stuff. I think that what’s quite interesting is the way that I do a song is distinct from the way that the Who would do it, and I don’t want to deny myself all the Who-type material because y’know, that’s what I am.

Sometimes I feel like [I want to sing a song I’ve written myself]. Sometimes I feel that I get a little too precious about a song, and that I feel that I don’t really want to hear the band play it because I like the way it is on the demo. But I’m always pleasantly surprised. I think one of the great things about having done my solo album stuff and decided to chuck really quite nutty material in… is that the changes which have taken place between ‘Who Are You’ and my solo album have affected the next Who album.

Pete Townshend radio interview with Redbeard, In The Studio, 1996

Essentially what had actually happened to me was that I had realized that I developed a completely personal way of dealing with my creative life. Although I had grown up in a band, what I was actually doing as an artist, as a songwriter, and also to some extent as a stage performer, was performing in isolation. Alone as it were, in a bubble. Even feeling that way sometimes on stage with the Who. I didn’t feel particularly like part of a band. I felt like I was an individual in a band. I think one of the interesting things about The Who is that they are four individuals who happen to work well together as a band. I think today looking back I’m even more certain that that was a correct view of what was going on for me at the time. We’re talking about the late 70’s when I started to pursue a solo career in earnest, around ’78 or ’79, just after The Who had finished the Who Are You album.

I certainly felt very much as though my inner life, my creative life, the things that I wanted to say was not so much being neglected, but they were becoming narrower. It was less possible to incorporate them into the generality that The Who had become. Because I think what had happened was that we became better known for our more anthemic works like ‘Won’t Get Fooled Again’ and ‘Baba O’Riley’, rather than for the slightly more impish humour that we had started our life with. As I grew older I realized that I had lost the ability to express that sense of humour. Strangely enough when I started to write songs on my own, humour was about the last thing that emerged. The first couple of albums that I wrote were full of personal pathos. But that was really where it all came from. I think it was a clear view of myself as an artist, and a clear view of my own needs as an artist. It wasn’t I particularly felt the Who wanting in any way, I didn’t feel that they didn’t provide me with anything. I felt that I wasn’t serving them very well, and I thought that perhaps pursuing a solo career would in fact help me to serve The Who better. In actual fact, I think what happened was that I ended up stopping working for The Who at all.

Pete Townshend interview, October 2005 (published in petetownshend.com Diaries, 2006)

I was still reeling from Keith Moon’s death when Ina Meibach my New York lawyer and great friend persuaded me to consider punting around for a solo deal. She, like so many insiders, knew that I had a wider talent than was evident in my work with The Who, and felt that the depression descending on me around Keith’s death, and the concerns we all had about the future for The Who, could be dispelled if I could express myself creatively as a solo artist. My wife and I both had fears about it, but Ina brought such wonderful offers to the table that I decided to go ahead. I think it was probably a mistake – The Who went on in any case, and I then had too much writing to do. I suppose I felt I just couldn’t turn down such a fabulous opportunity to make a record for Atco – my favourite record label.

I’d say the album is an open admission off my alcoholic state. I had been drinking hard since the Tommy movie in 1975, so at least three years of overdoing it saw me in poor emotional health. But one of the aspects of alcoholism is depression see-sawing with grandiosity. The album reflects these aspects.

Working on the album with producer Chris Thomas

Pete Townshend autobiography, Who I Am, 2012

I started recording my solo album on 19 November 1979 with Chris Thomas, whom I’d met at Paul McCartney’s Hammersmith Odeon concert, for which he’d produced the recording. Rabbit was present for every track, and his work was phenomenal. I used several drummers. Kenney Jones was an obvious pick. James Asher had worked with me at Oceanic. Simon Phillips came in on a few tracks too; I’d loved his work with Gordon Giltrap. Chris had chosen Wessex recording studios where he’d recorded Never Mind the Bollocks, on the other side of London.

The solo album recording moved to AIR studios in Oxford Street, and the tracks started to sound better and better as more was added. Chris Thomas helped find a new voice on tricky songs like ‘Jools and Jim’, ‘Empty Glass’ and ‘Little Is Enough’ and to build really solid backing vocals in thick layers on pure pop songs like ‘Let My Love Open the Door’. Wherever my demos had good elements, Chris used them, like Glyn Johns before him. Chris had just completed the first Pretenders album with Chrissie Hynde. Chrissie had an extraordinary and unusual voice with a huge dynamic range, and Chris worked with her intensely, doing quite a lot of ‘comping’ – recording a number of vocal tracks, and then choosing, isolating and combining the best parts. By the time he worked with me he knew precisely how to get a virgin singer like me to find a real voice. There is no false modesty here: this was my first really serious solo album, and I had to learn to sing hard rock, high notes, low notes, and express passion and sexiness.

The Pete Townshend Tapes, 1980

I’ve got a lot of confidence about recording and writing, because I’ve been doing it for a long time. I’ve got a studio at home, or have had for a long, long time. And so I live in a studio, I’m familiar with all the ins and outs of that side of it. But I think what really gives the album it’s complete confident feel, is the fact that I was lucky enough to find absolutely the right producer to work with. Chris Thomas produced the album. Chris Thomas is probably currently most famous for the fact that he produced the Pretenders stuff, which he was working on at the same time he was doing the solo album with me. So I’m knocked out that they’re successful. I really like all their records too. But I met him when I recorded with Paul McCartney on the ‘Rockestra’ track, which is that thing where Paul McCartney got about 20 musicians, like 4 drums, 4 guitar players and stuff, and put an instrumental together on the ‘Back to the Egg’ album. And I saw Chris running around and said ‘What are you doing here?’ and he said, ‘I’m producing Paul McCartney.’ And I was absolutely amazed, because the first time that I met Chris Thomas, who came from the same town as me, Ealing in West London, I was producing him! In a group called The Cat. This was in 1966. And Speedy Keen, who was in Thunderclap Newman, wrote ‘Something in the Air’ and all that stuff, was the drummer in that group. I went back through Chris’s material, I listened to the Kokomo album, to the Procol Harum stuff that he’d done. I realized that he’d worked with the Sex Pistols. And I just thought, this has got to be the guy. And I rang him up, thinking he obviously must be the busiest man in the world, and he was really keen to do it. And I think it was a hundred percent right for me, cause I felt comfortable with him, we were brought up in the same neighborhood, we shared a lot of friends. I just felt really easy and he was able to pull out of me, I think particularly on vocal performances, a lot more sort of natural performance than I could get with anybody else. For a long time I was thinking of using various American producers, maybe Bill Szymczyk, who I really like and I like his work. Or Phil Ramone, who did Billy Joel and Paul Simon. Or maybe Tom Dowd or Jerry Wexler, you know, and all those great, great producers. But the problem is that they are Americans, and either I would have to go over to America or they would have to come over here, and there is a cultural difference. I felt that my solo album should first be me, and be English, and be recorded here.

Pete Townshend interview with Jenny Eliscu, Rolling Stone, 2000

I always had quite a nice voice, but I never owned it until 1980, when I did Empty Glass, with Chris Thomas. He said, ‘Why don’t you just sing?’ And I said, ‘Because I sound like Andy Williams.’ And he said, ‘So?’ And I sound like Andy Williams – I’ve got a beautiful voice.

Pete Townshend Interview with Kurt Loder, 1980

Most of the material is pretty up-tempo. I did have a couple of ballads I was thinking I might include, but I didn’t – mainly at the behest of Chris Thomas. He figured the album should be pretty ballsy, and that’s the way it’s come out.

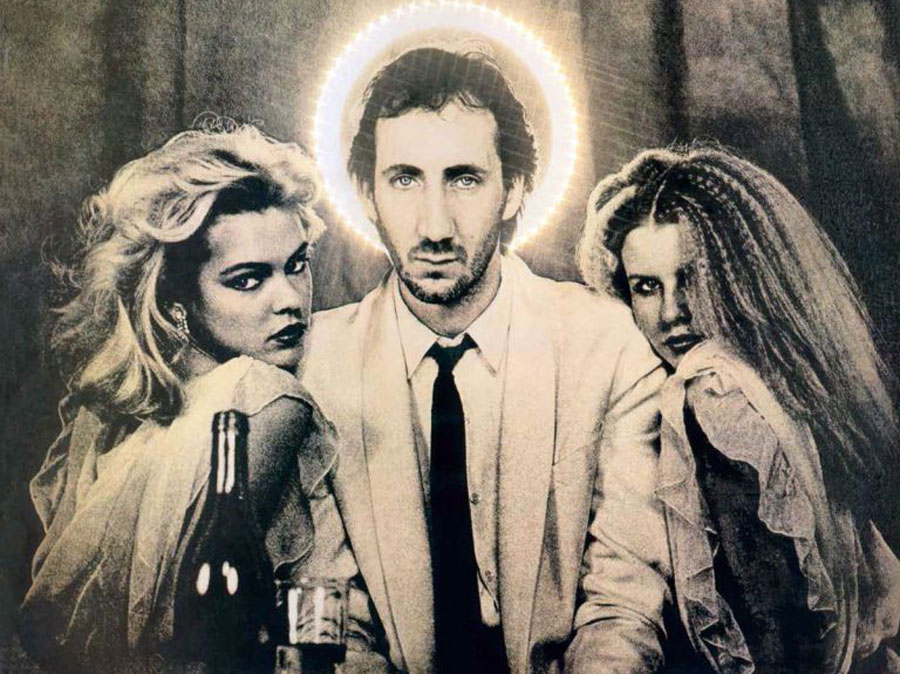

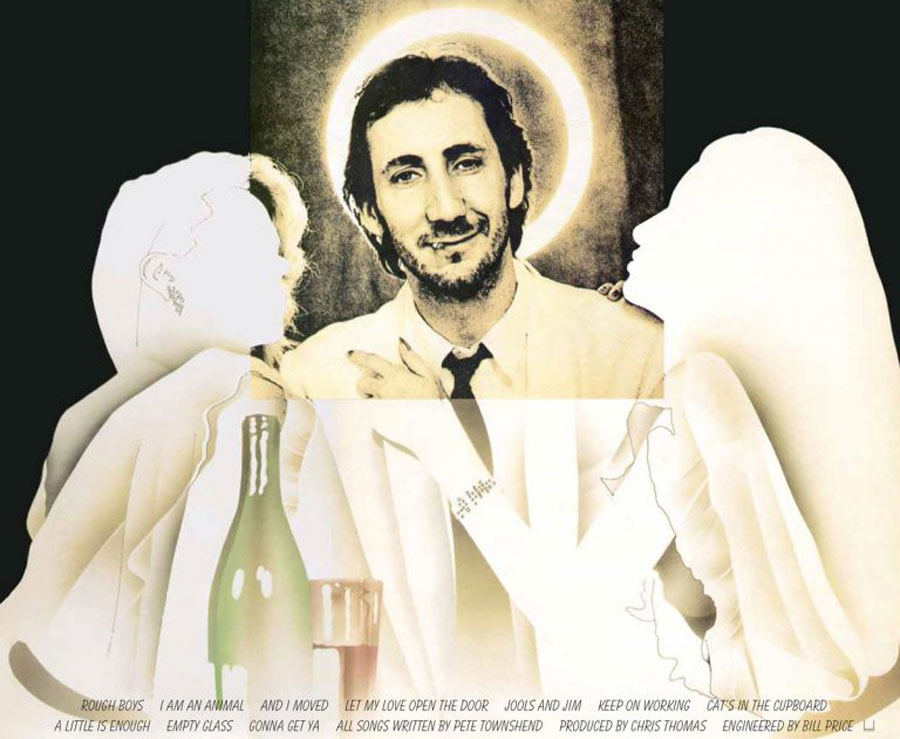

Album artwork

Pete Townshend interview with Charles Shaar Murray, NME, April 1980

Bob Carlos Clarke did the cover. He normally does semierotic stuff, bit like Helmut Newton but better. British photographer: he has to have women in his photographs. I asked him to do the cover and he said he’d love to, but it had to have women in it. At one point I was going to call the album ‘Sacred Animal.’

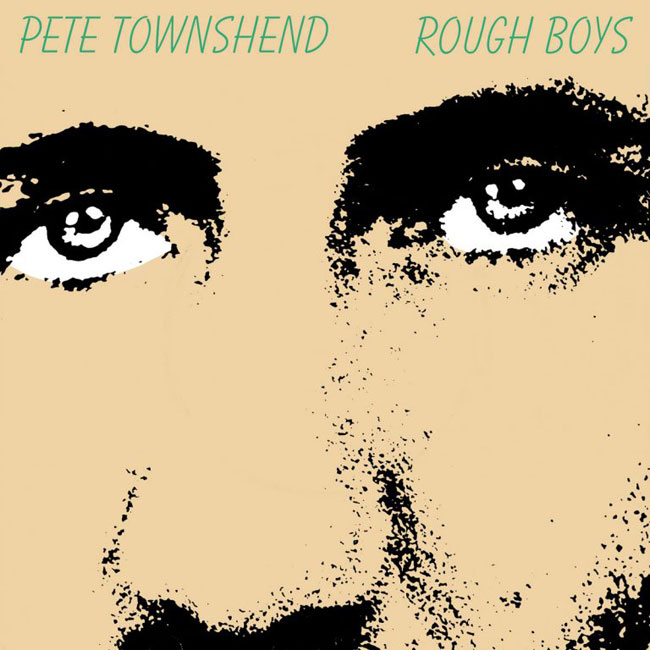

Rough Boys

'Rough Boys' was the debut single from Empty Glass, released in the UK March 1980 and reaching #39 on the charts. The B-side was 'And I Moved'. 'Rough Boys' was later released as a single in the US in November 1980, with 'Jools and Jim' as the backing track. It peaked at #89 on the Billboard Hot 100. On the album sleeve notes, Pete dedicated 'Rough Boys' to his children Emma and Minta, and to the Sex Pistols.

The Pete Townshend Tapes, 1980

This song is called ‘Rough Boys’ and this was chosen as a single from the album. Probably because it’s the most sort of obviously up-tempo noisy sort of track. This is the only song on the album which my wife doesn’t understand, doesn’t know quite what it’s about. But it’s really quite an innocuous song, despite all the parading that goes on, and the vocal gymnastics and pyrotechnics. It’s just a song about my neighborhood that I was brought up in, and the kids that live there. The way they are today, and the way I feel driving through or walking through, the memories I have and the feelings I have about being young again. Going back and growing up in the neighborhood I was brought up in all over again.

Pete Townshend liner notes, The Best of Pete Townshend, 1996

'Rough Boys' was made up on the studio floor. Entirely. I just made it up as I went along, and Kenney Jones played along. I had a synthesiser guitar which was running into two synthesisers – an ARP and a Roland, two early primitive guitar synthesisers. I used the Roland to generate the bass part with my thumb. I played ragtime. The chords were played with the middle three fingers and a melody of sorts was played with my little finger on the top string, all of which went to different synthesisers, each of which went to a huge Hiwatt stack in the middle of Wessex Studio, so I stood there on my own with Kenney bashing away on the drums, and produced this huge noise, which sounded like about thirty guitars, and what we actually added to the record was a bass, and what you hear is me going nuts in the middle of the studio. But the reason it’s so complicated at the end harmonically is because I was just playing anything that came under my fingers. I got my friend Raphael Rudd to come over and do a brass part for the end, and it took him a long time to analyse some of those chords at the end. Anything that didn’t work, we snipped out with a pair of scissors. Risk and trust, they call it. It works.

Pete Townshend liner notes, Scoop 3, 2001.

Tough Boys demo.

I recorded this onto a half-inch analogue 8-track Tascam tape machine in 1979. I had no proper studio at home in London anymore and had put together a temporary and transportable rig around this machine. Great sounding machine usually, but in this case I was simply chucking down a very quick demo of a strange sound I'd managed to cook up by combining a Roland guitar synthesiser (which was polyphonic) with an ARP Avatar (which was monophonic). I used the ARP on just the lowest string of my guitar, creating a rather erratic bass line. The chord sustain noise is from the Roland, and you can also hear the strings being strummed from a mike I put near them. In the studio (Wessex) when I recorded the track properly I fed each output of the two synthesiser into a separate amplifier, creating a monstrous and wobbly wall of sound. This demo was all I had when I went into the studio to start working on Rough Boys for the album Empty Glass. The lyric came together in the studio, a rant about the British punks (like Sid Vicious) I had come across in recent years who wore outfits I had come to know in New York as the apparel of 'rough' gays. Not sure why or when the title changed.

Pete Townshend radio interview with Redbeard, In The Studio, 1996

The punk explosion in the UK was just starting to diminish a little bit. I suppose I was in the studio around 1978 so it had been happening for a while. What it had deteriorated into was a kind of fashion exercise. It was young men walking up and down Kings Road with very very spiky vaselined hair, rings in every nose and leather gear, dog collars, lots of studs, lots of leather. Like most people, I found it a very tough and really quite intimidating look. But it also reminded me and evoked to me the kind of Village People look that I had seen in New York several years before, which was also lots of dog collars, chains, leather, and vaselined hair. And I decided to make the connection. And so the song is about those – not so much gender issues that exist between this very sort of tough leather clad look that came from both the New York gay scene in the 70’s, but also from punk – but the sexual issues. The difficulties that are associated with both sexual prejudice. But also when we decide because somebody wears a particular outfit that they must be of a particular sexual persuasion, and how wrong we can often be. I suppose it was one of those ‘Don’t fuck with me’ songs. One of those songs about whatever the look, inside there is somebody that is strong and defiant, and is going to stick to their principles whatever happens. My girls would then have been about eight and ten, and I think what I really loved about them both at the time was that despite their daddy was in a rock band, quite a big rock band, and was obviously going through some kind of sea change personally, I think it was a very strange time of my life then. They were both very much their own people, they were both independent, they had their own ideas about what they were going to do with their life. And I think the song is about that. It’s about being true to your own feeling about yourself, to who you really think you are.

Pete Townshend interview with Alan di Perna, Guitar World, August 1996

I was looking at my own physicality, my own sexuality. It was all in a very unconscious way. I’d grown up surrounded by a very cosmopolitan and fairly wild bunch of people: Kit Lambert and Chris Stamp, Chris’s brother Terence Stamp, and Jean Shrimpton. These were some of the hot shot glitterati of London’s King’s Road scene in the Sixties. I’d been involved with that on the one hand, and with the Mods on the other – violent, tough street kids. There was all that in the past. And at the time of writing ‘Rough Boys,’ I was also feeling threatened – although I couldn’t figure out why – by what had been going on with punk. And that brought forth a whole tumbling array of ideas. I still use that technique when I write songs – brainstorming onto the page and trying to make sense of it later. But at those times, I wasn’t even trying to make sense of it. I was just brainstorming, period, and letting it appear on record. That was something that worked on that album.

I Am An Animal

The Pete Townshend Tapes, 1980

This song is probably the closest to a ballad on the whole album. It’s a song called ‘Animal’. It’s one of the favorite songs that I’ve written for a long time. I think probably my favorite song on my album. Although it’s a ballad, the subject material isn’t really your normal moon in June stuff. It’s actually a song about the evolution of the individual in a spiritual way. About all the different roles that we go through in one lifetime. Some times feeling like we’re big shots, and some times feeling like we’re not worth anything, and other times feeling like we’re pretty normal, sometimes feeling sort of very macho, and other times feeling very feminine and sensitive. Just about all the different facets that we go through. I think I’ve done most of the ones what I mentioned on the song, and I hope there’s a few left.

And I Moved

The Pete Townshend Tapes, 1980

On one of the songs that I recorded for the solo album, I tried out a piano technique which was taught to me by a friend of mine called James Asher. I produced a record with him once called 'Peppermint Lump', with a kid called Angie singing. And it’s a technique where you use a delay, an echo on the piano. And you play one finger piano, you go dunk, dunk, dunk, and the echo comes out after going diddly diddly diddly, and it makes you sound a bit like sort of a high speed Semprini. I use that technique on this track, which is called ‘And I Moved.’ The lyric of this song is actually quite controversial because a lot of people are quite confused about what it’s about. But it’s a song I actually wrote for Bette Midler, and she said it was a bit too dirty for her [laughs], which I’ll leave you to work out what it’s about.

Pete Townshend interview with Charles Shaar Murray, NME, April 1980

I don’t really know what the line ‘He laid me back like an empty dress’ is about. Originally I wrote it as a song about a voyeur, but it went through some permutations. A lot of people feel that it’s about me and my father or me and Meher Baba or me and a relationship with a woman, but I listened to it last night because I was checking the pressings, and I thought it was a bit like an admission of homosexual tendencies. ‘Rough Boys’ is more of a paternal thing, but ‘And I Moved’ is very peculiar and I think it’s probably best not to try and explain it. Originally I wrote it when Bette Midler’s manager had written to me and said she was doing an album, she liked what I wrote and asked if I could send her a song. He said, ‘Make it a bit dirty, because that’s the kind of thing she likes.’ So I sent it to her and heard nothing for a couple of months; then I heard from him and he said, ‘I couldn’t really give it to her because it’s smutty.’ I said, ‘What? You asked for something dirty’ and he said, ‘It isn’t dirty, it’s smutty.’ One of the purest pieces of schoolboy poetry I’ve ever written. You see it on paper: ‘And I moved towards him dot dot dot Pete Townshend 6B.’ Followed immediately by a pen drawing by Penarric, 7C.

Let My Love Open the Door

'Let My Love Open The Door' was released as a single in the US June 14, 1980, with 'And I Moved' as the B-side. It reached #9 on the Billboard charts. It was released in the UK on June 21, backed by 'Greyhound Girl' and 'Classified' that the sleeve notes describe as 'Two previously unreleased tracks found beneath the Eel Pie Floorboards.' The single made it to #46 on the British charts.

The Pete Townshend Tapes, 1980

At my house where I live, I’ve got a studio, a proper 24 track setup. It’s not a heavy recording studio situation, but I can work on proper recording tapes, like the big stuff they use in studios. And I actually recorded this track almost entirely at home. It’s called ‘Let My Love Open the Door.’ It’s a very simple love song. And I kept the kids, and the wife, and the guests that were staying with us awake until 5 o’clock in the morning recording it.

Pete Townshend liner notes, The Best of Pete Townshend, 1996

Let My Love Open The Door is one of those songs where you end up shooting to write something really deep and meaningful, and what you end up with is something that appears to be froth. This was a song about love, but this is actually about divine love. It’s supposed to be about the power of God’s love, that when you’re in difficulty, whether it’s major or minor, God’s love is always there for you. But I suppose, because I used the royal ‘we’ – I sang with God’s voice – it became a song about, you know, ‘Hey, girl, I’ll give you a good time, if you’re feeling blue, come over to my place, and we’ll catch a movie,’ very much a soap opera version of what it was about, but a few people have picked it up.

Jools and Jim

The Pete Townshend Tapes, 1980

I take the Guardian, and once I was reading through the morning nonsense, another plea for women’s emancipation. And I noticed an article about two rock writers who write for the NME, called Julie Burchill and Tony Parsons, and it was actually an interview with them. And in the interview, I think it was Tony that said that he didn’t really care much about the fact that Keith Moon was dead because, good riddance to bad rubbish kind of attitude. I wasn’t really incensed as such, apart from the fact that they had compared Keith to Sid Vicious, which I thought was a bit peculiar. I felt that the only way that I could get out the anger that I felt was through writing a song. And this is the song that I wrote as a result of reading this interview. It’s called ‘Jools and Jim’.

Pete Townshend interview with Charles Shaar Murray, NME, April 1980

I wrote the song after someone from the Guardian wrote an article about [Julie Burchill and Tony Parsons] to promote their book, and he got very animated about how they didn’t give a shit about Sid Vicious going down. Then Tony brought up Keith as well and said, ‘Fuck Keith Moon, we’re better off without him. Decadent cunt driving Rolls Royces into swimming pools; if that’s what rock ‘n’ roll’s about, who needs it?’ To a certain extent I agreed with a bit of it, but I feel that it was a bit of opportunist cock. I just wrote the song as a reaction. I rang Tony up the day after I’d written it and explained. I was going to send him a copy, and then I decided I wouldn’t send him one until it came out after I’d decided that it was a good song to go on the album. I thought ‘Fuck it, he’ll get it in the end.’ I only read their book the other day and I quite liked it. I changed the title from ‘Jools and Tone’ to ‘Jools and Jim’ because it’s not directly about them; it’s about taking a stance and believing what you read. It’s just another ‘don’t believe what you read’ song. I think it’s one of the best songs on the album. The energy’s great and I really like the singing on it.

Keep on Working

'Keep On Working' was released as a single in the UK November 1980, with 'Jools and Jim' as the B-side. It failed to chart, and was not released as a single in the US.

The Pete Townshend Tapes, 1980

There are two songs that I wrote for The Who, which I included on my solo album. They are not so much Who rejects, but they are songs which I wrote for the Who Are You album, which we recorded but which because albums only have a limited amount of space didn’t actually get on. One is called ‘Keep On Working’. It’s just a song about living in England really.

Pete Townshend interview, Musician, 1982

Ray Davies has always been a big influence on me. I’ve never been able to write in the same way, though I’ve often tried. In fact, I’m terrible at it. I think ‘Keep On Working’ tries to be a Kinks song but it just doesn’t work.

Cat’s In The Cupboard

The Pete Townshend Tapes, 1980

I did a concert at the Roundhouse, a solo concert, one of the few solo appearances that I’ve ever done before the paying general public. I often sit around and play the guitar for friends and things like that. I did a concert at the Rainbow for the Rock Against Racism cause after the riots and subsequent troubles that happened in the South here in England last year. I wrote a song especially for the occasion called ‘Cat's In the Cupboard’, and in fact I used two of the musicians at that concert that I used on the album. One is the bass player, Tony Butler, who plays with my younger brothers band called ‘On The Air’. I used him playing on every track on this album. I used a couple of different drummers. Kenney Jones played on ‘Rough Boys’, and Simon Phillips played on most of the rest of the stuff. But Tony played bass on all this stuff, and he was actually at this concert. It’s just like a really out and out blues stomper. It’s called ‘Cat's In the Cupboard’, and it’s got Peter Hope Evans playing harmonica.

A Little Is Enough

'A Little Is Enough' was the third single released in the US October 1980. The B-side was 'Cat's In The Cupboard', and it reached #72 on Billboard. It was not released in the UK.

The Pete Townshend Tapes, 1980

Of all the songs that I’ve written lately, I think that this is probably the one which you could say was truly inspired. I don’t normally wake up in the middle of the night screaming ‘Eureka!’ or ‘Blazing Saddles!’ I just sort of scribble and it turns to what tends to come out. But this one is called ‘A Little Is Enough’. I had a thought one day that really, we are all at the end of a great long queue to get to whatever it is that we’re gonna get to. And everybody wants more of whatever it is that they're after than they’ve already got. If people are rich then they want more, and if people are poor then obviously they want more. And everybody is in sort of a pecking order. I just thought about the quality of love, and how really to be in love once, or to feel love once is enough. Because once you’ve experienced it, it lives with you and it stays with you and it becomes part of you. And it doesn’t matter how small an amount you get, because it’s a kind of infinite quality. Something about it that is so sort of powerful and infinite, once you’ve tasted it, it’s with you for life, as it were. This particular thought inspired this song.

Pete Townshend interview with Greil Marcus, Rolling Stone, June 1980

With a song like ‘A Little Is Enough,’ what was interesting to me was that I was able to very easily put into words something that had actually happened to me when I was a thirty-four-year-old. It wasn’t self-conscious; it wasn’t a song written from a stance. It wasn’t objective. It was purely personal: instant, and purely transparent. It’s very emotional, but it’s also very straightforward and clear. Just the fact that you can’t fucking have the world. If you’re lucky enough to get a tiny piece of it, then – fine. When that’s applied to something as immense and intangible as love – whether it’s spiritual love or human love . . .

I suppose I wrote the song about a mixture of things: I wrote it a little bit about God’s love. But mainly about the feeling that I had for my wife – and the fact that I don’t see enough of her, and that when we are together there’re lots of times when things aren’t good, because of the period of adjustment you require after a long tour: stuff like that. She would always want a deeper, more sustained relationship than I would–but in the end I suppose we’re lucky that we do love one another at all. Because love, by its very nature, is an infinite quality, an infinite emotion – just to experience it once in a lifetime is enough. Because a lot of people don’t – don’t ever experience it.

A lot of the songs on the album – well, ‘Let My Love Open the Door’ is just a ditty – but particularly ‘A Little Is Enough’ and a couple of the others – ‘I Am an Animal.’ I think – are getting close to what I feel I want to be writing: in terms of somebody who’s thirty-five writing a rock song, but one which isn’t in the George Jones – Willie Nelson tradition – ‘I’m a smashed-up fucker standing at the bar . . .’

Pete Townshend radio interview with Redbeard, In The Studio, 1996

I think I was very clear about what I was writing. I wanted to write a fairly light hearted song about love in it’s most general form. You know the idea of love as a force which helps people to help each other through identifying with one another. If you attempt to convey a sense of compassion and empathy with another human being, I think that is the beginning of a process of real love and care for other people. The song's really about that. I suppose a spiritual love, a reflection of Gods love. But I also felt that I started to get a bit high flown in my attempts to work in this particular area. I thought that maybe it would be possible to write a pop song which on the surface would appear to be a song about a man claiming that he had, you know, a big dick or something, and his ability to make the girls fall in love with him was bigger and better than everybody else’s. I think to begin with that’s how the song came over. But I think in due course the underlining theme of it has landed.

We were having a conversation once [with Adi Irani, Meher Baba’s secretary for a long time], and I think I was right in the middle of working on this record Empty Glass, and I was having a hard time. I was very over stretched and had financial difficulties, I had all kinds of problems. But the main problem for me at the time was I was experiencing my first real glimpse of marital breakdown I suppose. He said ‘How do you feel about this?’, and I said, ‘Well I feel terrible!’ He said, ‘So she said she doesn’t love you, so what did you say?’ So I said, ‘I asked her if she loved me at all’, and she said she might love me a little bit. He said, ‘You know Pete, that should be enough. A little should be enough’. I said, ‘How can a little be enough, when you are talking about something as important as love?’ and he said ‘It’s precisely because we are speaking of love, because love is infinite. It emanates from Gods most supreme universal manifestation. Everything is motivated by it. Everything is driven by it. A tiny fraction of that complete ocean is as important as the ocean itself. So in the case if she loves you a little, then that should be enough.’ And I kind of carried that off and it saw me through what was a difficult couple of years. And it’s actually seen me through a lot of lean times I think, because I think it’s very easy to forget that we should be grateful simply for being alive. We should be grateful simply for seeing the sun come up. Today I’ve got a much better sense of that philosophically speaking than I had when I actually wrote the song. So it means a lot to me. I think I have grown into it, and it seems like a very wise thing for me to have written when I was actually quite so fractured.

Empty Glass

The Pete Townshend Tapes, 1980

One other song that I wrote, probably 1977, 1978, which was recorded actually by The Who but was never released, was a song called ‘Empty Glass’ which is the title track of my solo album. I got the idea from reading Ecclesiastes, that part of the bible that King Solomon sat there talking about how he’s seen everything, you know, ‘I’ve seen everything, I’ve done everything, I’ve done the lot mate. And it’s all boring.’ And I was so staggered to actually find this sort of degree of apparent negativity in the bible. But I read it again and again, and then I realized that the message was not a negative message at all, but probably one of the most powerful and exciting parts of the bible. I know a lot of other people, sort of artists and people like that always sort of get excited when they read Ecclesiastes. And it brought forth this song.

Pete Townshend interview with Greil Marcus, Rolling Stone, June 1980

‘Empty Glass’ is a direct jump from Persian Sufi poetry. Hafiz – he was a poet in the fourteenth century – used to talk about God’s love being wine, and that we learn to be intoxicated, and that the heart is like an empty cup. You hold up the heart, and hope that God’s grace will fill your cup with his wine. You stand in the tavern, a useless soul waiting for the barman to give you a drink – the barman being God. It’s also Meher Baba talking about the fact that the heart is like a glass, and that God can’t fill it up with his love – if it’s already filled with love for yourself. I used those images deliberately. It was quite weird going to Germany and talking to people over there about it: ‘This ‘Empty Glass’ – is that about you becoming an alcoholic?’

Pete Townshend interview with Charles Shaar Murray, NME, April 1980

The spark-off for the song ‘Empty Glass’ was when I read Ecclesiastes again, and it was so powerful it just reminded me of the way Britain is today. Everyone walks around complaining about one thing and another, but when they’re talking about futility – if you’re talking about Britain as a country with a history and an empire – they’re talking about futility after a consummation. Bringing it closer to home, to my age group, after winning the war you end up with fuck all. You got King Solomon talking about how after he’s fucked everybody and had everything and gone through everything, the only piece of advice he’s got is that life is useless. But it also contains some great inspirational poetry: ‘There is a time’ and all that. It really reminded me of a lot of Persian Sufi poetry, that it’s only in desperation that you become spiritually open.

I don’t know what religion is. It’s a machine that surrounds spiritual need. Spirituality is the need, and religion is the junk food, really. What’s amazing about finding something like Ecclesiastes in the Bible is to realize that what it is is a refutation of religion as society and junk food, if you like. It’s to say, ‘Listen, you won’t get what you want through sex, through people, money, through overeating. Through triumph, through anything. The only way you’ll get it is by getting on your hands and knees and asking for it.’ Spirituality to me is about the asking, not the answers.

I still find it a very romantic proposition, that you hold up an empty glass and say, ‘Right. If you’re there, fill it.’ The glass is empty because you have emptied it. You were in it originally. That’s why it’s only when you’re at your lowest ebb, when you believe yourself to be nothing, when you believe yourself to be worthless, when you’re in a state of futility, that you produce an empty glass. Normally, you occupy the glass. By emptying or vacating the glass, you give god a chance to enter it. You get yourself out of the way. In a sense, it’s to do with semantics, but ultimately, you vacate. You ask for help. I can’t back this up, but I think that when I’ve sincerely prayed, I’ve gotten an answer of some sort. Not in the ways I’d ever imagined I’d get an answer, but I’ve gotten one.

If you go on challenging life, saying ‘Why won’t life do something for me? Why am I the one who’s always losing?’ then all you’re really doing is perpetuating life as is, the ideal that life revolves around you as the center of the universe, which is not true. It’s not realistic and it’s not practical. You’re just another fucking cog in the wheel and you’re nothing. You only mean something and you only become something when you believe yourself to be nothing. That’s why I put that little footnote on the cover, which was only a repeat of something Meher Baba said: ‘If you want nothing, then you’ve got everything.’

This thing that I was talking about before about empty glass: it’s this whole thing about the innocence and purity of the heart; whatever you do the heart will remain pure. But you have to go out and suffer life; you can’t just sit there going, ‘I am pure. Peace will come to me.’ The song’s about this guy sitting at the bar and waiting for life to come to him and say, ‘You have won a star prize!’

Pete Townshend radio interview with Redbeard, In The Studio, 1996

I was groping for a title for the album which would demonstrate that what I believed at the time was that I was there really with an empty heart. I felt that I was ready to undertake a journey but I wasn’t particularly equipped. All that I knew was that my heart was like an empty glass, waiting to be filled with something. And I grabbed at the idea because Hafiz and Rumi, both well known poets from Persia, both use the analogy of Gods love being like wine. Being a very heavy drinker at the time, it was like a kind of mischievous way to bring in my difficulties with alcohol at the time. My glass was always empty, always. You know, because if I filled it, I drank it immediately. That led directly to a sense that as fast as I tried to fill the hole in my soul, I realized that that was an impossible job. That was not something that I could do. That hole in my soul had to be filled in some other way. By the time I got to Chinese Eyes, I think I was dealing with that metaphor far more directly.

Gonna Get You

The Pete Townshend Tapes, 1980

My solo album closes with a track called ‘Gonna Get Ya’ which is music for walking in the park to, or driving your car to. Music to crash cars by. It’s not actually about anything at all, it’s just a word game and it’s just an out and out rock track. What I love about it is Rabbit's beautiful piece of piano in the middle. We did this in one take, this song. We did just one pass at it. And Rabbit produces a real kind of Keith Jarrett almost piano break in the middle which I absolutely adore. And I don’t think I’ll ever tire of this track because of that. Because I love Keith Jarrett’s work, and I don’t think Rabbit will ever get the chance to have as much freedom on Who material as he has on this track. I think it’s wonderful.

Researched and written by Carrie Pratt.