Happy anniversary to The Who’s Tommy album, which was released 50 years ago this month!

The Who began recording sessions for Pete Townshend’s critically acclaimed rock opera on September 19, 1968 at IBC Studios in London, and wrapped up work on March 7, 1969. The album was released by Decca Records in the US on May 17, 1969 and on Track Records on May 23, 1969 in the UK. Tommy reached No. 2 in UK charts and No. 4 in the US.

When Pete Townshend began work on recording his demos for Tommy in the late 60’s, he had a grand vision of doing something fresh and new to move The Who in a different direction. Up until that time, they were primarily a pop singles band, who were starting to struggle to get chart topping records. It was the end of the 60’s, and heavier long form rock albums were taking over in popularity. Pete knew they needed something bold and new to help save the band. They needed a hit album.

Pete had experimented with composing shorter concept pieces on previous Who albums, such as A Quick One and Rael, and he wanted to expand that idea to a full blown concept album. He was encouraged by The Who’s manager Kit Lambert to create a rock opera, complete with a formal overture. Kit was the son of classical composer and conductor Constant Lambert, and he wanted Pete to use elements of opera and to mix classical music with rock.

Pete began composing songs about a deaf, dumb and blind boy that were inspired by the spiritual teachings of Indian mystic Meher Baba, who Pete followed closely at the time. The first song he wrote for the album was Amazing Journey, and he built up the concept of Tommy on a spiritual journey from there. To help fill out the story, Pete pulled in songs that were written a few years earlier that he thought fit into the storyline. He recorded demos of his songs in his home studio to help sell the band on his concept album idea.

Pete brought his demos to the recording studio sessions, and discussed the story extensively with Roger Daltrey, John Entwistle, Keith Moon, and Kit Lambert, who produced the album. The band provided input and exchanged ideas for the album. They ultimately gave Pete their full support and complete artistic license to realize his vision. Kit helped to structure and arrange Pete’s compositions. John was enlisted to write the songs ‘Uncle Ernie’ and ‘Cousin Kevin’, which Pete wanted in the story but was too uncomfortable to write himself. The Who worked together in unity to record their ultimate version of the songs, taking the music to a whole new level. A masterpiece was created.

During the creation of the album, they went through a number of names for what to use as the album title as the story evolved, including Amazing Journey, The Brain Opera, The Deaf, Dumb & Blind Boy, Journey into Space, and Omnibus, before finally landing on Tommy.

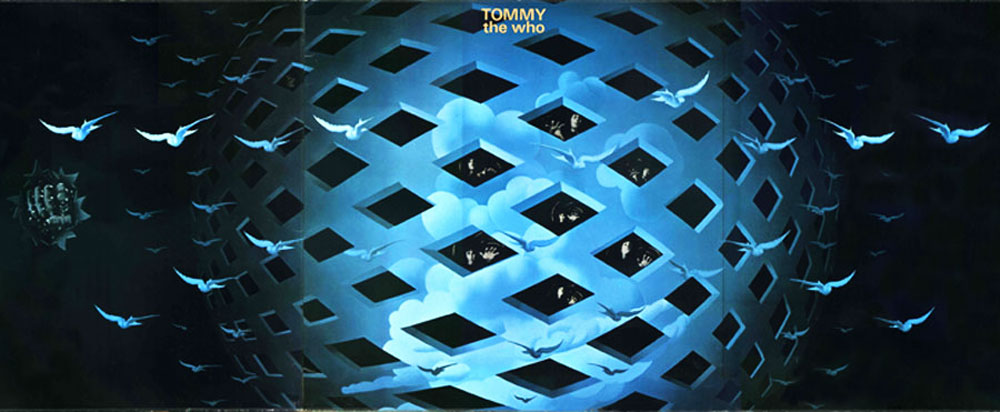

To help tell the story of Tommy in visual form, Pete worked closely with artist and fellow Baba follower Mike McInnerney throughout the making of the album. Mike designed the album cover and did all the beautiful illustrations for a libretto style lyric book that was included with the album.

Pete came up with the idea of making Tommy a pinball wizard instead of a guru in order to lighten the heavy spiritual overtones, and to score a good review from his journalist friend Nik Cohn, who was a fan of pinball and was writing a book called Arfur: Teenage Pinball Queen. The song Pinball Wizard was released as a single a couple months before the album, on March 7, 1969. Without the context of the full story, many critics felt the song about a deaf, dumb, and blind boy was distasteful and 'sick'.

The critical reception changed after Tommy was premiered at the album’s press launch at Ronnie Scott’s Jazz Club in London on May 1, 1969, where the audience was bombarded by a full throttle performance by The Who at an extremely loud volume. Tommy was hailed by the journalists who attended as a groundbreaking masterpiece. A couple days later, on May 3, BBC Radio 1 premiered a few tracks from the LP.

The Who debuted songs from Tommy at the Grande Ballroom in Detroit, during three performances May 9-11, 1969. Tommy transformed The Who’s live performances, and took them to the next level. The rock opera became the centerpiece for their stage show, and they promoted it with extensive touring in 1969 and 1970, including performances at the Metropolitan Opera House, Woodstock, and the Isle of Wight Festivals.

The Who have brought back Tommy in their stage act many times since, usually as a powerful medley of the songs. They have also performed a few full length presentations of the rock opera, including the 1989 Los Angeles concert with guest appearances by Elton John, Phil Collins, Billy Idol, Steve Winwood, and Patti LaBelle. Roger Daltrey performed Tommy on tour with his solo band in 2011, and again in 2018 with a full orchestra conducted by Keith Levenson. The Who performed what was billed as the first ever live performance of Tommy in it's entirety at the 2017 Teenage Cancer Trust benefit shows at the Royal Albert Hall.

There have been a multitude of Tommy spin off projects over the years, such as Lou Reizner’s London Symphony Orchestra album in 1972, and Ken Russell’s film in 1975. Tommy has been performed as a stage production numerous times, including productions by the Seattle Opera in 1971, the Les Grands Ballets Canadiens in 1971, and the Tony Award winning Broadway musical directed by Des McAnuff in 1993, which has since become a staple production for hundreds of regional theatre companies all over the world.

The music of Tommy is universally loved, and is still as popular and vibrant today as it was 50 years ago.

To celebrate this milestone anniversary, here is the history of Tommy, told primarily in Pete Townshend’s own words, sourced from various interviews over the years.

STUDIO ALBUM

Pete Townshend interview with Jann Wenner, Rolling Stone, September 1968

Well, the album concept in general is complex. It’s derived as a result of quite a few things. We’ve been talking about doing an opera, we’ve been talking about doing albums, we’ve been talking about a whole lot of things. We’ve condensed all of these ideas, all this energy and all these gimmicks, and whatever we’ve decided on for future albums, into one juicy package. The package I hope is going to be called 'Deaf, Dumb and Blind Boy.' It’s a story about a kid that’s born deaf, dumb and blind and what happens to him throughout his life. The deaf, dumb and blind boy is played by The Who, the musical entity. He’s represented musically, represented by a theme which we play, which starts off the opera itself and then there’s a song describing the deaf, dumb and blind boy. But what it’s really all about is the fact that because the boy is D, D & B, he’s seeing things basically as vibrations which we translate as music. That’s really what we want to do, create this feeling that when you listen to the music you can actually become aware of the boy, and aware of what he is all about, because we are creating him as we play. It’s a pretty far out thing actually. But it’s very, very endearing to me because inside, the boy sees things musically and in dreams and nothing has got any weight at all. He is touched from the outside and he feels his mother’s touch, he feels his father’s touch, but he just interprets them as music.

Pete Townshend interview with Keith Altham, New Music Express, November 16, 1968

I wanted to get an appreciation of things through the eyes of someone or something that was not preconditioned by the bias of the senses. I thought of looking at life through the eyes of animals, adolescents and finally the deaf, dumb and blind boy. The boy registers everything in the form of musical vibrations. That is if he is struck a blow – he does not feel pain – he experiences something like the chord of G. In the beginning he is abused by his family, raped by an uncle and given drugs like LSD to help his condition. Because of his disabilities he develops a technique which enables him to become a pinball playing champion. His sight begins to come back and he becomes obsessed by his own reflection in a mirror – then his hearing is restored when his mother shatters the mirror. He finally ends up as a kind of national hero who lectures on his disabilities and how he overcame them – a kind of cross between Billy Graham and a rock and roll star. He founds a holiday camp (this is Moon's idea) where all the people try to become like him by wearing eye patches, ear plugs and having corks in their mouths. In a way I am mocking myself because the album contains ideas and attitudes which are very important to me personally and by placing them in front of the Who they have destroyed them. It helps you put something into perspective sometimes if you can take something you really care about and laugh at it. In a small way the album is a solution to the way that might achieve divinity because I have no faith in evolution and science only reveals another two things to be revealed.

Pete Townshend interview with Richard Green, New Music Express, March 22, 1969

There's already been a reaction in America and they haven't even heard it yet! I expect some controversy but I don't want it to get out of hand. I've been thinking about it for ages. I've had a number of ideas to write a sort of pop opera. It puts across a number of value... gives a modern idea of what good and bad is. A simple feeling of spiritual development in day-to-day living. To use a normal guy wouldn't have been unusual enough for mystery. The deaf, dumb and blind boy can feel jolts and bumps and things which can be translated into music. He isn't born like it, it's a block instilled by his parents. He sees his dad murder his mother's lover and they tell him he hasn't seen anything or heard anything. Gradually, he loses his senses because of the pressures put on him, and the album goes into his musical experiences. He spends all day in the arcades and becomes a pinball champion, playing by feel. A doctor starts to remove the block with a strange technique. The boy has to look at his own reflection and in the end that's all he sees. He isn't affected by anything around him and he becomes a sort of pop hero and in the end becomes what all boys would like to be. He opens a holiday camp and the whole thing develops into a religion almost. But it all becomes a bit nasty. It adds a new facet to what can be done in pop music. It's some of the best stuff I've ever written, equal to 'My Generation'. I never set out to write anything as good as that, but it just happened. It will take the place of the old act, but with no tricks or costumes or special lighting.

Pete Townshend interview with Rick Sanders & David Dalton, Rolling Stone, July 12, 1969

Glow Girl led me to the idea of 'It's a Boy, Mrs. Walker.' But that would have been too blunt an opening so I did the 'Overture.' This clues you in to a lot of the themes and gives a continuity to the individual tracks – you think you've heard them before because they've been stated in the overture. It gives more of a flow and strengthens the whole thing.

The boy has closed himself up completely as a result of the murder and his parents' pressures, and the only thing he can see is this reflection in the mirror. This reflection – his illusory self – turns out to be his eventual salvation. In general terms, man is regarded as living in an unreal world of illusory values that he's imposed on himself. He's feeling his way by evolution back to God-realization and the illusion is broken away, bit by bit. You need the illusions until you reach very pure saintly states. When you lose all contact with your illusory state, you become totally dead – but totally aware. You've died for the last time. You don't incarnate again – you just blend. It's the realization of what we all intellectually know – universal consciousness – but it's no good to know until you can actually realize it. Tommy's real self represents the aim – God – and the illusory self is the teacher; life, the way, the path and all this. The coming together of these are what make him aware. They make him see and hear and speak so he becomes a saint who everybody flocks to. The boy's life starts to represent the whole nature of humanity – we all have this self-imposed deaf, dumb and blindness – but this isn't something I'm over heavy on. I'm more concerned about what actually happens in his life. Having lost most of his senses, Tommy feels everything simply as rhythms and vibration. Everything reaches him as music. He gets everything in a very pure, filtered, unadulterated, unfucked-up manner. Like when his uncle rapes him – he is incredibly elated, not disgusted, at being homosexually raped. He takes it as a move of total affection, not feeling the reasons why. Lust is a lower form of love, like atomic attraction is a lower form of love. He gets an incredible spiritual push from it where most people would get a spiritual retardment, constantly thinking about this terrible thing that's happened to them. In Tommy's mind, everything is incredible, meaningless beauty.

You see, each song has to capsule an event in the boy's life, and also the feeling, what has ensued, and cover and knit-up all the possibilities in all the other fields of action that are suggested. All these things had to be tied up in advance and then referred back to. I can tell you it was quite difficult.

We can't play 'See Me Feel Me' on stage for laughing now, but when I first wrote it, it brought tears to my eyes. It's meant to be extremely serious and plaintive; but words fail so miserably to represent emotions unless you skirt around the outside, and I didn't enough there. You can circumscribe an emotion with a lyric – by telling of an event and leaving out one important chunk – and that can contain an emotion and put it across. This one fails because it actually comes out and says it. But there's so much circumscribing in Tommy that I wanted to get to the crunch a number of times.

The song 'Acid Queen' is not just about acid: it's the whole drug thing, the drink thing, the sex thing, wrapped into one big ball. It's about how you get it laid on you that you haven't lived if you haven't fucked 40 birds, taken 60 trips, drunk 14 pints of beer – or whatever. Society – people – force you. She represents this force. On a number of occasions I've got this sinister, feline, sexual thing about acid, that it's inherently female. I don't know if I'm right it's fickle enough.

'Pinball Wizard' has already been notably successful as a single, though it wasn't tailored for that purpose. The whole point of 'Pinball Wizard' was to let the boy have some sort of colorful event and excitement. Side Three is supposed to be really explosive. Suddenly things are happening; it starts to move really fast. 'Pinball Wizard' is about life's games, playing the machine – the boy and his machine, the disciples with theirs, the scores, results, colors, vibration and action. Tommy's games aren't games. They're like the first real thing he's done in his life. I play games – an incredible number. But I do real things as well. No this is Tommy's first big triumph. He's got results. A big score. He doesn't know all this; he stumbled on a machine, started to pull levers and so on, got things going, and suddenly started getting incredible affection – like pats on the back. This hasn't happened to him before, and the kids are his first disciples. It's supposed to capsule the later events, a sort of teasing preview. It's meant to be a play off of early discipleship and the later real disciples. In a funny sort of way, the disciples in the pinball days were more sincere, less greedy than later on, when they demand a religion – anything to be like him and escape from their own dreary lives, do things his way and get there quicker.

'Sensation' is the song Tommy sings after he's regained his senses. He realizes who he is and becomes totally aware. The sound of the song is like the Beach Boys; the moment is that of divinity. Tommy is worshipping himself, knowing what he is and speaking the truth. I used all the sensation stuff because after all this time where Tommy's just been getting vibrations, now he's turned the tables. Now you're going to feel me! I'm in everything; I'm the explosion; I'm a sensation. Our influences in the Who are often directly attributable to certain things that certain groups have done at certain times. But 'Sensation' is indefinable for me. I can't put my finger on where it came from.

'I'm Free' came from 'Street Fighting Man.' This has a weird time/shape and when I finally discovered how it went, I thought 'well blimey, it can't be that simple' – but it was and it was a gas and I wanted to do it myself but some of them are quite remote. I listen to a lot of music so I'm open to a lot of influences.

Pete Townshend interview with Derek VanPelt, Cleveland After Dark, November 19, 1969

The mirror sequence was one which was in mystical terms, and even in Christological terms, if we explain that Tommy's predicament was a mental or spiritual block. He witnessed a traumatic event, and the key that people have missed was that the event was mirrored. We purposely obscured the fact of his witnessing a murder in the mirror; but the key is that in the background vocals on '1921' you got reflections – "You didn't hear it (I heard it)," and so forth. What we get to is the point that Tommy has lived the whole of his life able to see only his own reflection. What happens is that he focuses on his reflection and sees himself as a Messiah, something which he obviously is not. The reflection is the only other person in the world. As he gets older he becomes dependent on that vision. When the mother finds out that this is what's going on, she smashes the mirror and brings him into the real world. And because of the trauma, of that event, it balances his witnessing the murder and equalizes his physical state, restoring his senses – he transcends his old physical state and his spiritual state as well.

The last song (We're Not Gonna Take It) was a very particular part for me. I explained it after I wrote it. There, Tommy becomes for all intents and purposes the equivalent of a Messiah. The people see him as someone who has conquered the biggest problem of all. They see him as someone who has transcended. They see him as an answer to their problems – all these things like, "My mother wants me to cut my hair," ridiculous little problems like that. They come to him and tell him, "We want to do it your way... I want to skip that, I want to get through." He encourages them, very simply: come to me, be like me; "welcome to this house" – be in my presence, you might learn the simple fact of life. Uncle Ernie sees what Tommy's doing. He sees that Tommy is inviting kids to be around him and that the kids are anxious to get religion. So Uncle Ernie cashes in. But Tommy doesn't go against that. The kids have gone along with it, and Tommy sees that. Uncle Ernie is taking advantage of the situation and is trying to make money, and at the same time Tommy sees that the common people are accepting this and going along with it. He realizes that it's beyond his control. They are demanding something that he can't give. He'll have to force them through to the point where they see that he cannot give them anything which they haven't already got. They aren't going to do it by blinding their eyes and stuffing corks in their mouths. They are going to have to do it in their own way. Where he ends up is that he has suffered his crucifixion purposely, for himself. They've run out on him – not accepted him for what he is but for what he says – left him.

Pete Townshend interview with Tony Wilson, Melody Maker, July 19, 1969

Well, I'm obviously not 100% satisfied the album. The original aim was to record it, and we did what we wanted. That was to make an album that told a story like an opera does, but keeping the rock'n'roll format, which was much harder to do than it looked. It was quite a heavy story told in quite a heavy way. The way it worked out actually was like literature. It wasn't meant to happen that way, but nothing happened in 'Tommy' itself that wasn't to happen.

Pete Townshend interview with Keith Altham, Record Mirror, December 13, 1969

I think 'Tommy' is reflective of the mood of a generation. It's one where the see-saw has been over heavy at one end for too long and youth is now at the point where it has to make the decision – the bulge that is – whether to grow old, whether to swing to an intuitive way of living a genuine way or the way our forefathers did which is like throwing shit around! I think it is going the right way and that there is a real mental revolution taking place in the minds of these young people and one step nearer the spiritual revolution which will follow.

Pete Townshend interview on Dutch TV, 1970

Pete Townshend interview with Connor McKnight & John Tobler, ZigZag, April 1,1974

The bit from 'Rael' and 'Glow Girl' aren't connected with Tommy directly, they are utilisations of bits that were lying about. 'Glow Girl' was a separate song. I used that bit from the 'Underture' in 'Rael' because we were doing 'Rael' in New York and Kit was cutting down from several hours to about two minutes and it wasn't working and I thought that was my trump card. So I thought those chords which I had and loved and played all the time to myself – and handed those over and put a bit of lyric on them – in the studio and felt when we were doing Tommy that I wanted to use them again, that they were under-played. I still feel that the 'Sparks' section that we did on stage on Live At Leeds gets close to what's possible for that classical rock thing. I always imagine a classical conductor with his hair flying. The Who and Keith are incredibly capable of those classical flourishes. The expressive Wagnerian dynamics stuff. That's what I really wanted to come across, whereas 'Underture' and 'Rael' were really a bit lilting. They're not really connected at all. It's just that Tommy was long and in the end we were digging about a bit so we pulled from all sorts of sources. Tommy is a direct illustration of the way I write a lot. Maybe tomorrow I'll think up an idea that will use up all the ideas that have been lying around for a long, long time. That seemed to be what happened with Tommy. Everything fell together like a jigsaw. I'd sit and think what I wanted was a bit of a vignette like Tommy in the theatre with all the kids screaming, and I had this song called 'Sally Simpson' about this little girl who fell in love with a rock star. 'I'm Free' was written long before Tommy was ever thought of. What else? 'We're Not Gonna Take It' without 'Listening To You' tacked on the end. That was written in as a suggestion of Kit's. 'See Me Feel Me' was also Kit's idea. You see, he really had a lot to do with it. He was thinking operatically, and I was thinking rockatorically. He was suggesting things to me from his deep operatic thing, which I'm beginning to get an inkling of now.

It definitely seemed to be a piece that was out of my control – the whole thing. Kit Lambert never did that much, the group never did that much. I did all the graft, but it definitely seemed to be something that was happening outside of me. Something was putting it together. In a way I don't identify with any of it. I identify much more with 'We're Not Gonna Take It' as it was originally written. It was a song about police brutality. You know – we couldn't take it from Hitler and we're not gonna take it from you. It was a British song, if you like. It was what 'Won't Get Fooled' said but a bit earlier. Applied to that situation it worked well. It was very considered writing, in that respect, but somehow the whole thing as a complete thing, including songs by other people and including all the suggestions by Kit, and including the fact that it took the group ages to do – when it was finished with the cover and everything – I looked at it and thought this was my work and this is my expression. I'm taking it, and I did take it and express it and talked about it and found out about me and what I was intending subconsciously. But I don't suppose I'll ever work under the influence of Kit Lambert again.

Pete Townshend interview with Steve Peacock, Sounds, April 5, 1975

The other thing I wanted to do was to make the thing have a spiritual meaning, to make the point that individual experience is what counts, and that Tommy's experiences had earned him a kind of super-consciousness which everybody else was on the way to having anyway, but because they see and are attracted to this miraculously charismatic figure, they're sidetracked into believing that this is the way to do it. They lose the sense that their own lives are tailor-made for them. That they mustn't change is the lesson. And at the end, the thing that I really wanted to get across – it's very ill defined as to what Tommy actually is and I haven't really adopted a stance on it – but he's definitely not a messiah as such, he's not a Meher Baba. He's ... a saint? Maybe just ordinary, ordinary and invigorated by being ordinary after so many years of not being so. The spiritual aspect was the whole motivation for writing it. I wasn't necessarily trying to disseminate spiritual ideas or help people or anything like that, but I did by then have a very nice understanding of what communication with rock and roll was all about – you say something and you get back something, and the thing repeats until the oscillation speeds up to the point where there's an amazingly locked-in sequence. And I wanted spiritual stuff, wanted it, so it was almost like throwing it out to get it back. I felt very much at the time that I had to move away from the druggies that surrounded the group, the people who really saw the Who as a heavy psychedelic band, the people who'd put tabs of acid in your coffee before you went on stage ... I felt devastated by all that. I was very mystified by the fact that 'Tommy' was so financially successful because it was the first really good, well-intended thing that I'd ever done – the first time that I'd really wanted to do something good – and in that way I suppose I was trying to put out spiritual ideas, and it then embarrassed me that it had to make money. This is it, put on your Salvation Army uniform and your Rolls Royce arrives in the post, your place in heaven guaranteed right here on earth. Maybe deep down I do feel that Tommy is me, although I've always resisted saying that in the past. People ask whether it's autobiographical and I've never, ever felt it as such: it's drama to me, theatre, but maybe on thinking about it that's the only reason ... The only other thing is that maybe while I was writing it I imagined him as what he turns out not to be, as a messiah figure, in which case I don't think I could have put a face on him as such.

Pete Townshend interview with Richard Barnes, The Story of Tommy, 1977

When I first started writing Tommy he was not deaf, dumb and blind. The first song that I wrote – 'Amazing Journey', that was the absolute first song of Tommy – that was like the pivot point and as a song it more or less tells you everything that you want to know about the story of Tommy. You know "deaf, dumb and blind boy, he's in a strange vibration land" etc, etc. What the lyrics really mean is that though he can only feel things, from these feelings they become like music to him, and the music that he sort of feels and the vibrations become important to him, and it becomes like his guide and his leader and his master. I was actually going to try to cope with this on quite a grand scale, I was going to try and create pieces of music which represented his feelings at any given point, but him being deaf, dumb and blind initially was just a sort of thing I grabbed out of the air.

What I wanted to do at that particular time was to be sort of musico-diplomatic, I wanted to hit everybody all at once. So I did, cautiously, put across a spiritual message because I did feel that I had learnt a fantastic amount through my life and perhaps even through dope, which had led me to Baba,and I knew that Baba was something very special and I wanted this all to be wound up. But at the same time I wanted Tommy to be rock and roll, I wanted it to be like singles that you could pull out and play. You could pull out 'I'm Free' and 'Sensation' and they'd be good just as songs. I didn't really want the thing to have any musical flow, you know like themes connecting it, I just wanted it to be a series of singles that happened to tell a story.

Pete Townshend interview with Alan di Perna, Guitar World, 1996

I was playing a fair bit of piano in the composition. It was the first time that I'd really started to be confident that I could play the piano. But I was also working with the 12-string acoustic guitar as a free composition element. So on stuff like 'Sparks' and 'Underture,' I used a big Harmony 12-string, Leadbelly-type guitar, sort of a copy of an old Stella. And I'd been tuning it into a kind of pick-driven ragtime. For example, I might play a drone on a D and play chords on the top. I used that to some extent on 'Welcome' as well 'Come to this house, be one of the comfortable people...' which is quite an interesting song. It was entirely written in free time. It's in 6/8, but there's no strict rhythm, just a gentle, 'homey' kind of style that was produced on the guitar rather than in my head. It came from the feeling that I got from playing the guitar, from approaching the guitar as a comfortable, domestic kind of instrument. But in the opening of 'Overture', you hear what, in a sense, is very much a personal style of pick-driven acoustic guitar playing that not many other people do. I don't know what it grew out of, I think it was through a mixture of listening to blues and jazz, particularly to Mingus, at the same time. That two-finger thing that Mingus used to do on the piano all the time. It's there in the 'Captain Walker didn't come home' bit, with a little bit of country stuff thrown in. I still love to play that way today.

Pete Townshend interview with Simon Goddard, Uncut, February 2004

I'm not very good at selling my ideas in advance. That's why I've always done demos, because when I talk I always tend to talk too much, I tend to roll over the subject and end up on the other side of it. I was kind of thinking, 'How can I rescue The Who?' I had to fight very hard to hold on to my own guns, which was that I felt we needed to do something about the spiritual journey. It seemed preposterous and I could only demontrate it by doing it. Which is how Tommy began, as a series of demos. What I remember is that everybody kind of fell in behind me. I remember that very warmly. That trust, and how elegantly they fell in behind me. It wasn't until I played the studio tapes again and hear the chit chat between takes that I suddenly realised what a really great Who session it was.

Pete Townshend excerpts from Who I Am autobiography, 2012

I made a huge leap into the absurd when I decided that the hero would play pinball while still deaf, dumb and blind. It was daft, flawed and muddled, but also insolent, liberated and adventurous. I had no doubt whatsoever that if I had failed to deliver The Who an operatic masterpiece that would change people's lives, with 'Pinball Wizard' I was giving them something almost as good: a hit. I decided Mike McInnerney would be the first person to hear it. Mike and I had spent lots of time brainstorming about the music for Tommy and the way Mike's illustrations would complement it. Meher Baba taught that life as we knew it was 'an illusion within an illusion', an angle Mike was developing for the album sleeve. The front cover and one of the inside panels showed a kind of latticed grid through which listeners had to pass in order to reach the music inside.

Meher Baba had spoken about 'God playing marbles with the Universe', and the newly introduced pinball element echoed that in Tommy. Mike was thinking about a new painting for the record sleeve to depict the way that illusion deceived us into believing that what we saw was real, but he was running out of time. His illustration work in gouache was meticulous and time-consuming. He decided to create a photograph instead, and enlisted someone he knew to set it up.

The problem for us both was to work out what the function of Tommy would be now that Meher Baba was gone. I had never intended for Tommy to be a proselytising vehicle for Meher Baba, but it was certainly intended to reflect spiritual yearnings during these post-psycheledic times. Youth movements were dividing and polarising into two camps - political activists and spiritual seekers, and I saw myself in the latter. We discussed whether Baba's name should be credited on the sleeve and agreed that it should, but merely as 'Avatar'.

Kit had left the first mix and assembly of Tommy to our IBC studios engineer Damon Lyon Shaw. When I first heard the double album I was a little taken aback. Kit had remixed the entire album so that the band was very low behind the vocals, and some tracks seemed to lack the punch I knew they had delivered in the studio. But the collection hung together better, and after a few listens I decided Kit had taken the correct approach. The story behind Tommy was fairly easy to follow, and the sleeve would contain the words as well as sensational pictures; practically every lyric line could be clearly heard in the mix, and this - after all - was the whole point. Mike McInnerney's sleeve design was a triumph. It added mystery and coherence, a seemingly impossible combination. Printed up and held in hand it was an object of beauty as well as elucidation.

Pete and Roger at the screening of The Who Sensation: The Story of Tommy, 2013

Excerpt from documentary The Who Sensation: The Story of Tommy, 2013

LIVE PERFORMANCES

Pete Townshend excerpt from Who I Am autobiography, 2012

On 31 March [1969] we went into rehearsal in a hall in West Ealing. It took just four days for us to realise that Tommy was going to be a wonderful piece to play live. After the last rehearsal Keith took me for a drink, looked me in the eye and said, 'Pete, you've done it. This is gonna work.' Our rehearsals were a revelation: the music of Tommy, when played live, even in an empty hall, generated an extraordinary, building energy, and seemed to possess an inexplicable power that none of us had expected or planned.

As critics gathered like a pack of baying, snarling dogs, we prepared to face them. The only way to stem the attacks would be to play the first live show of Tommy in London exclusively to the enemy, to the cynical British press and radio media. On May Day we took the stage at Ronnie Scott's Jazz Club to premiere Tommy live to a bunch of music journalists half drunk on booze we'd provided. As we walked on, one or two shouted out: 'Townshend, you sick cunt, smash yer guitar.' The audience murmur began to build; the situation didn't look good, so we drowned out the objectors by turning our amplifiers up far too loud for the small club, and began to play. By the time we had finished everone was on their feet. We had triumphed. The music worked.

The Who premiered Tommy at Ronnie Scott's Jazz Club in London, May 1, 1969.

Credit: Monitor Picture Library / Getty

Credit: Monitor Picture Library / Getty

Woodstock Festival, August 16, 1969

Isle of Wight Festival, August 29, 1970

The Summit Houston, November 20, 1975

Roger Daltrey talks about Tommy during his solo tour of the album, 2011.

The Who performed Tommy to benefit Teenage Cancer Trust, Royal Albert Hall, London, March 30 & April 1, 2017

Pete Townshend speaking to the audience at the end of Tommy performance for Teenage Cancer Trust, Royal Albert Hall, April 1, 2017

Some of those songs are really hard to listen to. You know I was abused when I was a child, and I find a lot of this stuff really hard to hear, and really hard to play. But this charity is about kids, about bringing kids back from much worse places than I went to and what happened to me wasn't that serious. But it fucked me up. Until I wrote Tommy. And then when I wrote Tommy, I looked at it and I thought, 'fuck, where did that come from?' And I started to remember. You know, I'm not going to be playing Tommy very often. I find it much too hard.

Trailer for The Who's Tommy concert, Royal Albert Hall, London, 2017

Pinball Wizard from Roger Daltrey's orchestral Tommy tour, 2018

LOU REIZNER'S LONDON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA PRODUCTION

In 1972, Lou Reizner conceived of and produced an orchestral version of Tommy with the London Symphony Orchestra and Chambre Choir, conducted by David Measham, and arranged by Wil Malone. The production featured an all-star cast, with Pete Townshend (Narrator), Roger Daltrey (Tommy), John Entwistle (Cousin Kevin), Sandy Denny (Nurse), Steve Winwood (Father), Richie Havens (Hawker), Maggie Bell (Mother), Graham Bell (Lover), Merry Clayton (Acid Queen), Ringo Starr (Uncle Ernie), Rod Stewart (Local Lad), and Richard Harris (Doctor). The double album was released in October 1972, in a beautifully designed package with artwork and photography in a booklet for the lyrics. The album was launched with two live performances by the LSO and cast at the Rainbow Theatre in London on December 9, 1972, with Peter Sellers replacing Richard Harris. The show had a second run with a different cast at the Rainbow on December 13 & 14, 1973. Lou Reizner brought the show to Australia for a couple of shows with mainly local players who performed at Melbourne’s Myer Music Bowl featuring Keith Moon as Uncle Ernie on March 31, 1973, and at Sydney’s Randwick Racecourse on April 1, 1973.

Pete Townshend interview with Charles Shaar Murray, New Music Express, March 3, 1973

"We weren't really all that involved with Lou Reizner's Tommy. There was a fantastic amount of business involved, and there was a difficult management thing. The reason that I was there was really to push the fact that this was a happening project, rather than a packaging job, so that people like Stevie Winwood and Richie Havens would want to do it. It was a Lou Reizner production. I had nothing to do with it except that I wrote it. I agreed to be on it because I felt it would be fun. I didn't agree to be on it because I felt it was the high point in my career. I feel I made a mistake doing the live gig, I don't think I should have been there. Some people liked, it, and some people thought it looked just like a pantomime. I liked the building up to it, but in retrospect I didn't like it very much. The whole point of doing it was for charity, and so we couldn't spend too much. They took £22,000 and the charity ended up with £10,000. I thought that someone was running off with the money, and sure enough, when we looked at the books all the money had been spent on production. Just to build one of those silly mushrooms costs about £500 for two of them, when you need them in a hurry.

Lou Reizner's orchestral Tommy with all-star cast, Rainbow Theatre, London, December 9, 1972

Interview with Lou Reizner about Melbourne production, 1973

Lou Reizner's Melbourne production of Tommy featuring Keith Moon, March 31, 1973

TOMMY THE MOVIE

The story of Tommy lent itself perfectly to the cinema, and soon after the album was released in 1969, Kit Lambert went to work on finding someone to turn it into a movie. After a few years of searching for the right script and director, Tommy was made into a film by director Ken Russell, which was released by Columbia Pictures on March 19, 1975. Roger Daltrey starred in the lead role of Tommy, launching his cinematic career. The film featured a star-studded cast, including Elton John (Pinball Wizard), Tina Turner (Acid Queen), Eric Clapton (the Preacher), Ann-Margret (Mother), Oliver Reed (Mothers boyfriend), Jack Nicholson (Doctor), Paul Nicholas (Cousin Kevin), Robert Powell (Captain Walker), and Keith Moon (Uncle Ernie). Pete Townshend and John Entwistle also appeared in the film in the scenes with Elton John and Eric Clapton. The film was extremely popular, and picked up a few awards. Ann-Margret won the Golden Globe award for Best Actress, and the film won the Rock Movie of the Year award at the Rock Music Awards. Pete Townshend was nominated for an Oscar for his movie score work.

Pete Townshend recorded the soundtrack music for the film at Ramport Studios and Eel Pie Studios. He included a few new songs to help fill in gaps of the storyline, and instrumental segments to link between songs. Pete used synthesisers extensively throughout the soundtrack, and brought in musicians Kenney Jones, Ronnie Wood, Caleb Quaye, Phil Chen, and Nicky Hopkins to record backing instruments behind the actors who sang the vocals. The soundtrack album was released March 1975 by Polydor Records. A single of Elton John's performance of Pinball Wizard was released on March 26, 1976.

Pete Townshend interview with Tony Wilson, Melody Maker, July 19, 1969

The film will be made by Universal International. The group will have a hand in the screenplay and the script, but not in the direction. We'll be working with a scriptwriter, but at the moment we have not really got anybody lined up at all. All we've got is the budget of a couple of million dollars. Who will play in it? None of The Who. Steve Marriott? We'll have to bend the story a bit. The main thing is to get the basic, simple concept in rock'n'roll high spirits. You couldn't have some of the visual things on film. Some things, which may seem quite sick, would be encapsulated.

Pete Townshend interview with Derek VanPelt, Cleveland After Dark, November 19, 1969

We intend to make a film of it with MGM starting next year. We finally got over a lot of things like contracts and finances, that kind of bullshit. We got the release from Decca, and now we're getting down to working with directors.

Pete Townshend interview with Caroline Boucher, Disc and Music Echo, January 26, 1974

The main difference with the film version of Tommy will be that the high points are higher and the low points are lower. The dynamics of it are increased. And what I found was that having someone highly creative like Ken Russell going through the script, opened a door in it so I could see something new. We started off by recording 'Pinball Wizard' and 'I'm Free', but they came out sounding such a cliché, and things were proving to be very slow. I think it's because it's very hard for us to get excited about playing something like that without an audience, so we've asked along quite a few other musicians to help us to give it a new breath of life. Eric Clapton's coming down, and he's also been offered a part in the film; and Kenney Jones, Ronnie Wood, and Nicky Hopkins is going to do the piano work.

There's no question that Ken is not a sensationalistic sort of director and so things like the Acid Queen, and the murder scene immediately appealed to him. I suppose Tommy does hold water, but there have always been sections that were a bit strange. The opening section is confusing, because you're not sure if Captain Walker or the lover gets killed, you're not sure when, or who the lover is, or whether Tommy saw it happen. And there's a kind of emptiness, characterlessness about Tommy. You don't ever feel the sense of him growing up, and he seems to only emerge as a positive character in the last song. It's something I'm rather bad at — developing characters and making them convincing, you've really got to be somebody to do that.

Pete Townshend interview with Richard Robinson, Hit Parader, May 1974

Ken Russell and I have already talked a fantastic amount. I've had lots of scripts from people, but this was the one that was right. I've never really been in on the making of a film from start to finish. If Tommy and my involvement in it does nothing else other than drag me back yet again to the industry charisma that surrounds it. At least it will teach me a bit about the making of a film.

In a moment of insanity I offered to re-do the music for the film which will start right after this tour. So as soon as I get back I want to write some additional material. I don't know, I've never seen anybody that I really respect ever take a piece of music of their own and re-vamp it and re-work it without something going wrong. It's like it never seems to work. I'm very anxious that what I do should be a reaction to Tommy as though from a completely different position. I think that it's long enough ago that it will evolve in a really good and exciting way. See, the other thing is there never ever was a rumoured live album of Tommy, and so there's nothing on record which represents the tail end of the Who's evolving Tommy.

Trailer for Tommy the Movie, 1975

Trailer for Tommy the Movie, 1975

Behind the scenes of Tommy the Movie, 1975

Pete Townshend interview with Simon Goddard, Uncut, February 2004

As a composer you believe you're king, but even when you compose for a movie, even if the movie is your composition, as it was, Ken Russell was the king. So what would actually happen is we'd go into the studio, he'd sit with his eyes shut, we'd play and he'd say, 'No, this bit needs to be longer,' and I'd say, 'Well, what do you want us to do?' and he'd say, 'Just make it longer, I need more time.' So we'd play a longer track and you'd find that would be Ronnie Wood pissing about on a slide guitar for 15 or 16 bars and then you'd find that when it's finished, the editor decides that it's not enough music to cut to so he'd loop up stuff, and then I would have to work on these loops. I just felt like a dogsbody. I thought, 'Where's the music?' There are bits of the Tommy film, in the 'Acid Queen' bit, for example, where you see Tina Turner doing all her stuff and you hear this loop going round with some sound effects chucked on top of it in a hurry to try and make it sound a bit different. I didn't feel that I would ever, ever, ever be able to work with a director again, and I never have. I loved working with Ken and I loved doing the Tommy movie, but once is enough.

Pete Townshend interview with Matt Kent, Tommy the Movie DVD Collector's Edition DVD, 2004

STAGE PRODUCTIONS

The first stage production of Tommy was put on by the Seattle Opera, which was staged at the Moore Theatre in Seattle April 28 thru May 16, 1971. Bette Midler appeared as the Acid Queen. A ballet dance production of Tommy was also staged in 1971 by Les Grands Ballets Canadiens. In the Spring of 1978, Pete Townshend saw a musical production of Tommy starring Allan Love that was staged by the Queen’s Theatre in Hornchurch, Essex. Pete was impressed enough to help transfer the production to the Queen’s Theatre in London, which opened February 6, 1979 and ran for 118 performances. This was the first West End stage presentation of Tommy.

In 1991, Pete Townshend collaborated with theatrical director Des McAnuff to write and produce a musical adaptation of Tommy, which opened at the La Jolla Playhouse in 1992, moved to the Saint James Theatre on Broadway in 1993, and had a revival at the Shaftsbury Theatre in the West End of London in 1996. That production picked up multiple awards, including 5 Tony Awards in 1993 (Pete won Best Original Score), 4 Drama Desk Awards in 1993, 3 Lawrence Olivier Awards in 1997. Sir George Martin produced the original cast album, which won a Grammy Award in 1993 for Best Musical Show Album. Similar to Tommy the Movie, Pete Townshend wrote new music for the Broadway musical, including the duet 'I Believe My Own Eye' between Tommy's parents, and updated some of the lyrics and storyline to better fit the theatrical production.

The Broadway stage production of Tommy has continued to flourish in regional shows throughout North America and Europe over the last 25 years.

Pete Townshend interview with Derek VanPelt, Cleveland After Dark, November 19, 1969

A lot of people have come to me personally about putting on a ballet or opera – not legitimate opera, but small companies, modern opera, something like Brecht's Three-Penny Opera. I've passed them all on to our manager. So far nothing has happened in that area. There were a lot of Midwestern ballet companies, but one of the things they always insisted on was having my interpretation of Tommy, which I can't give. What I put into it and what I got out of it myself were thoroughly different. It's very difficult to clarify Tommy to people. There is an off-Broadway production scheduled in 18 months; it will be something similar to Hair, but more serious and more intelligent – still intended to make money.

Tommy musical, Seattle Opera, 1971

Credit: Ken Howard

Credit: Ken Howard

Tommy ballet, Les Grands Ballets Canadiens, 1971

Pete Townshend and Allan Love interview, Queen's Theatre, London, 1979

Opening night of Tommy musical on Broadway, St. James Theatre, March 29 1993

Pete Townshend interview with John Heilpern, Vogue, May 1993

The cipher to Tommy was adolescent rage. It was rooted in the inarticulate desperation of our first fans, and maybe of myself. At the same time, I followed the teachings of the Indian master Meher Baba. A lot of Tommy was also based on Sufism, which interested me. So what I wanted to do was to tell the story of a boy who is on a spiritual journey but who doesn't know it. And I tried to create a metaphor to demonstrate it, which is that we are all as deaf, dumb and blind to our own potential as the character Tommy is in the rock opera.

Right now, it's about finding out what happened at the end! We never really had an ending. And if we could find it, we'd know where this poor sap has to go to get there. What I discovered in returning to Tommy was that in all it's vagueness, it's a story about a real person and a real family. I discovered that Tommy's awful neglect and traumas, the terrible abuses, the lovers, the murders – emotional murders – all of those things actually happened. They happened to me. I saw them as a young child. I saw the adult world at its worst. And I saw it at its best, because my parents finally got back together again. But I saw an ending. And so I do have an ending to Tommy. Which is that one forgives one's awful parents for everything they've done. Because if you don't, you'll spend the rest of your life going fucking crazy.

Documentary on the Broadway production of Tommy, 1993

Pete Townshend interview with Stephen Gallagher, British Youth & Popular Culture, December 12, 1996

When I met Des McAnuff I was pretty much committed to working with somebody. I had decided that the time had come to try and get Tommy into the theatre properly. I felt that it was time to initiate something from the ground up. And when I met him I just really got on with him. He was very positive about me in the early conversations that I had. He seemed to be thinking on similar lines. Obviously my experience was much deeper in terms of rock performance and his was much deeper in terms of developing plays and working with classics. But it was an instant recognition.

The difference between the La Jolla and Broadway versions was the second act had to be more showbiz. It wasn't just about flashing lights and pinball machines blowing up and things like that. It was about using encores, bringing back the good songs and using techniques that I knew about from rock performance. The giveaway was it suddenly became "Oh What A Lovely War". It stopped being what it had felt. It stopped feeling purely autobiographical. It stopped feeling like a rock classic. It stopped feeling like a story about a bunch of kids from Shepherd's Bush or whatever. And it started to feel to be a story about Britain and the mechanics by which Britain had in the past medicated itself. The message of "Oh What A Lovely War" was that if we blow our leg off what do we do now? Sing a happy song. And there's a kind of irony in that, a poignancy and a tremendous tragedy. But there's also hope. And it's poignant and it's sad and it's pathetic. And all of those things gathered together to produce a result which certainly not everybody that went to see Tommy and go to see it now get.

They were doing a piece about rock in music theatre in the American Daily News and mentioned Tommy as being the first one that had had financial success and they said it was ruined by a happy ending tacked on by the producers. I wrote to the Daily News to defend myself and said of course it wasn't tacked on by the producers. It was tacked on by me. And it was because I felt that what had actually happened on the record when it appeared in the late 60s was that there was a peace and love and suicide ethos. Now the suicide bit wasn't evident really in society. It was only evident in showbusiness. It was evident that one of the outcrops of our lifestyle was a kind of nihilism. When you looked at the fans closely, the people that grew up with that music, you found that it was just as prevalent in their worlds as it was in showbusiness. The same proportion of people who committed suicide as did in showbusiness. The same proportion of people who died in drink-related car crashes. The same proportion of people had taken drug overdoses. But you wouldn't have thought so. And so what actually happened was that somehow the ending of "Tommy", which was really about being destitute, being spiritually empty, being useless, it didn't reach the audience. I use exactly the same device at the end of Quadrophenia. Here is this boy who's spiritually destitute. He sings "Love Reign O'er Me" which if you like is the epiphanistic prayer to equal "Listening To You I Get The Music" at the end of Tommy in under exactly the same circumstances. There's very little left. Now what you see at the end of the Broadway production is Tommy going home and people interpret that as a fucking happy ending. I just don't understand it. I see him absolutely beaten by the family. I see him forced to stay at home because it's all he can do.

This seems to me to be the 90s version of Tommy. It's peace and love and being stuck at home. That seems to me to be what happens to so many modern people today. I don't see it as a happy ending at all. I see it as a deepening of the adversity, the difficulty that this young man is going through. He can put his childhood behind him. But what he can't do is erase the fact that he has to live with his family. He has to live with the consequences of his family. And that's very much what Quadrophenia did. But when Quadrophenia happened, because the context was slightly more realistic, it landed a little better. But it was also still slightly disguised. But today you see Quadrophenia and you know exactly what it's about. It's incredibly clear. Now I don't know what's happened in that time from 1973 to today. But with Tommy it was a little bit longer. And when I sat down to work on it with Des McAnuff I had to fight quite hard to get him to put on this so called happy ending. I said: "What would he fucking do?" He'd have to go home, partly out of sickness, partly because he would believe that there was some kind of vengeance available for him. But he'd also go home because there would be nowhere else to go. So to describe it as a happy ending seems to me to be just light headed.

I was very worried when we were putting Tommy up the first time in La Jolla that what would actually happen was that the ending would be deemed to be too sad. This poor kid has to stay with all these corrupt, horrible people. I wanted to see him climbing up the mountain as he does in the Ken Russell movie. But I thought it's not only unreal, it's also not what the journey is about. The journey is an internal journey. You can turn it into a metaphor in a movie. But in the theatre what you actually have to do is allow each member of the audience to create their own metaphor. Theatre doesn't do what movies do. Theatre doesn't say how it could be if only you were able to imagine everything and make it real. What theatre does is it brings you back to reality. When you're put out on the street after you've been to see a play, it's a very different feeling that you have than if you've been to a movie. I think I probably would have enjoyed to keep my own private pain out of my work. But I was changed by my audience who said your private pain which you have unwittingly shown us in your early songs is also ours.

I had had this bicycling accident. I decided that I was going to use the opportunity of this convalescence to go and talk to my mother. And it was an astounding conversation. Absolutely astounding. She told me a few things about my childhood. It was not only astounding because they were traumatic events but because they were things I'd grown up not knowing had happened. And yet what was astounding about them was realizing that everything that I had done creatively related to two or three incidents that happened to me when I was a child that I'd forgotten. Everything, absolutely everything. Certainly all of Tommy. And it was a real bone of contention when we came to argue the creative split based on the sweat factor with the other members of the Who. When I said it's autobiographical, you know, they said: "No it's not, we all played a part in writing the story". I was absolutely adamant: "No you fucking didn't, this came out of my subconscious, that's one place you can't have contributed to." So I went to Des McAnuff forcing stuff through. Where he was wonderful in catharsis and in creative exposition was actually simplifying, allowing me to just accept that something worked and it didn't need elaboration, it didn't need decoration. All it had to do was be presented. So a lot of it was about putting songs in the right order for the stage rather than a four-sided vinyl album or a 90-minute movie. And also encouraging me to believe that it was OK for me to rework, rethink and revisit what I'd done before.

Broadway cast of Tommy perform on Jay Leno's Tonight Show, 1993

Pete Townshend interview with Simon Goddard, Uncut, February 2004

When I sat down at the end of 1991 to work on the Broadway Tommy, I finally knew that there was a strong literal autobiographical component. Particularly in the opening scenes, which I hadn't really quit gotten before. Y'know, my father coming back and saying to my mother, 'We have to get back together for the sake of the boy.' So there was this almost metaphorical killing of the lover. It was the first time I'd realised where all this weird shit comes from. Sexual abuse, forcing drugs down children's throats, bullying, power struggles, family lies, family denials, secrets and then escape, defiance, the absurdity of the medical profession in the face of the complex post-war denial and then ultimately redemption through music and escape. That was it, really. And so I realised that that little story wasn't just my exorcising all this. It was actually my story.

Pete Townshend interview with James Jackson, The Times, April 20, 2009

Every manifestation of Tommy has had its price for me. Happily it has usually been lucrative as well. The music theatre version came late for me - I had tried to mount it in London in the late 1970s but it had clunked. There was always interest to try it again from New York, but I resisted. One day in 1991 I fell off a push bike, broke my wrist so badly that I was told I would never play guitar again, and possibly never be able even to hold a pencil. While I was still in plaster the offer to develop the Broadway production came in. I jumped at it, but said I would stay out of it, but was drawn in by my creative relationship with the director, Des McAnuff.

It was the most exciting and invigorating time of my life. The Who had been inoperative (at my behest) since 1982, and I got a taste of fame and glory again. I’m afraid it went to my head for a while. I quickly recovered when overwork led to me starting to drink again (after an 11-year break), but my marriage did not survive for very long after that.

In 1993 when Tommy went to Broadway I also staged Psychoderelict, my own solo musical, and later that year Iron Man at the Young Vic. So it was a year of intense and varied music theatre experience. At the end of it I promised myself I would never take a careless dig at Andrew Lloyd Webber or Richard Stilgoe again. The creative work behind a musical is almost beyond imagination in scale - and the problem is that unlike normal theatre, the story changes as the music is played, with each singer, with each phase of performance. As the composer and/or lyricist you have to be on your toes until the day the show closes.

Pinball Wizard from Tommy The Musical at the Shaftesbury Theatre, London, 1996