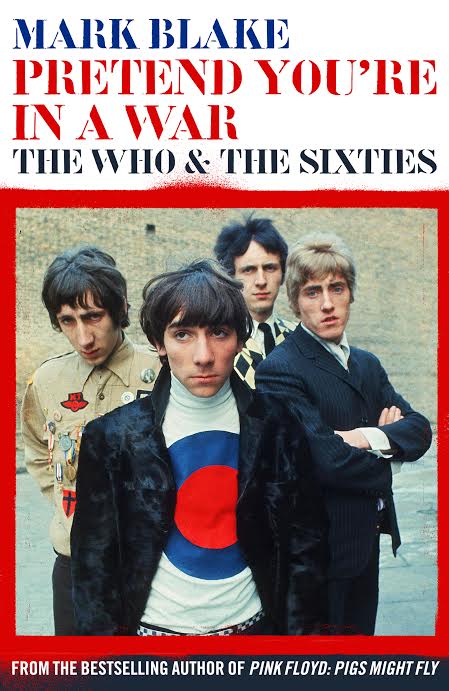

Pete Townshend was once asked how he prepared himself for The Who’s violent live performances. His answer? ‘Pretend you’re in a war.’ For a band equally prone to furious infighting, this could have served as a motto. Between 1964 and 1969 The Who released some of the most dramatic, confrontational and greatest music of the decade, including the singles ‘I Can’t Explain’, ‘My Generation’ and ‘I Can See For Miles’ and the albums ‘The Who Sell Out’ and ‘Tommy’. This was a body of work driven by bitter rivalry, black humour and dark childhood secrets, but it also held up a mirror to a society in transition.

Pete Townshend was once asked how he prepared himself for The Who’s violent live performances. His answer? ‘Pretend you’re in a war.’ For a band equally prone to furious infighting, this could have served as a motto. Between 1964 and 1969 The Who released some of the most dramatic, confrontational and greatest music of the decade, including the singles ‘I Can’t Explain’, ‘My Generation’ and ‘I Can See For Miles’ and the albums ‘The Who Sell Out’ and ‘Tommy’. This was a body of work driven by bitter rivalry, black humour and dark childhood secrets, but it also held up a mirror to a society in transition.

Former Pink Floyd biographer Mark Blake goes in search of its inspiration to present a unique perspective on both The Who and the 1960s. Through his own past interviews with Pete Townshend, Roger Daltrey and John Entwistle, and nearly 100 new interviews with ex-bandmates, producers, schoolmates, girlfriends, roadies, friends and enemies, Blake reveals how The Who, in their explorations of sex, drugs, spirituality and class, refracted the growing turbulence of the time. He also lays bare the colourful but crucial role played by their managers, Kit Lambert and Chris Stamp and – in the uneasy alliance between art-school experimentation and working-class ambition – he locates the motor of the Swinging Sixties.

Pretend You’re In A War: The Who And The Sixties by Mark Blake is published by Aurum Press in the UK on 18 September and in the US on 15 January 2015.

Order your copy from Amazon.co.uk or Amazon.com today!

Mark was kind enough to answer a few questions about his book in an exclusive new interview with petetownshend.net.

You selected to focus on The Who’s early years, a critical period of history when the swinging 60’s pop scene in London was at its peak. What made you interested in writing this book now?

The original pitch I wrote for this book brought The Who’s story right up to date. But I didn’t think it was working hard enough, or was bringing enough new ideas to the story. As time went on, it occurred to me that the part of The Who’s story that was the most interesting to me was where they and their early managers Kit Lambert and Chris Stamp come from, and what made them all tick. In my time as a music fan, buying records and going to gigs, The Who have only ever been a huge arena act. I was intrigued to find out more about what they were like way before then.

Did you want to take a modern look at the important social and cultural changes that the band was in the center of at the time, or was it simply designed to celebrate The Who’s 50th anniversary this year?

I had a gut feeling The Who would announce a 50th anniversary tour for either 2014 or 2015, but I didn’t know anything for sure. The timing of the book turned out to be a happy accident. But I didn’t address the social and cultural changes in the 60s in the book because of the anniversary. It struck me early on that The Who’s story in the 60s was inextricably tied in with all sorts of changes: the rise of the teenager and youth culture, the birth of rock’n’roll, changing attitudes to class, sex, drugs and religion, and, of course, the ever-present shadow of the Second World War.

How did you go about researching a project like this, and how different was writing this book from putting together an article for Mojo or Q Magazine?

I began by reading everything I could find on The Who and also the 1960s. I was already very familiar with the existing biographies (Richard Barnes’ Maximum R&B; Dave Marsh’s Before I Get Old and Tony Fletcher’s Dear Boy), so I started by looking for gaps in those stories and areas where I felt I could bring something new to the table. The next stage was making a list of the people I wanted to talk to, and in some cases actually track down. I’d previously interviewed Chris Stamp, John Entwistle, Roger Daltrey (several times) and Pete Townshend for Q and/or Mojo magazines. So I had a lot of original source material. If I were writing a magazine article about, say, The Who in the 60s, I’d probably need about four or five interviewees; I think I ended interviewing closer to 100 people for the book. Researching a book like this, you end up turning private detective. Also, if you’re looking for the band’s old schoolfriends and even ex-bandmates, you are searching for people in their late sixties or older, most of whom are retired and have nothing to do with the music industry. It can be difficult, but it’s very rewarding when you find them and, even better when they’re willing to talk.

As a rock journalist, can you discuss what it is about Pete Townshend and The Who that has attracted so much media attention over the years? What special ingredient do they have that draws you to want to write about them?

On a good day, Pete Townshend is the best interview in the business. I spent two and a half hours talking to him for Mojo in summer 2012, and I could have spent another two and a half hours talking to him. I think Townshend’s willingness to talk and his willingness to tackle some very unusual and sometimes difficult subjects in his writing is one of the things that makes The Who so interesting to listen to – and write about.

On a personal note, I also grew up in West London where a lot of the action in the book takes place. That also made me want to write about The Who’s early years. I knew the places they were talking about. I spent some time as a teenager in The White Hart in Acton and The Oldfield in Greenford. The first pub I ever got served in, when I was considerably underage, was The Railway Hotel in Harrow & Wealdstone, where Townshend first smashed his guitar in 1964. By 1981, though, it was notorious as one of the worst pubs in the area. I think I got punched in the face there, which is why I never went back. There was always a great tradition of violence at The Railway!

There are a lot of interesting and engaging characters connected to The Who over the years. Who were the key people that you interviewed for this book, and did Pete or Roger contribute at all?

Pete and Roger did not contribute to the book. Their respective ‘people’ were made aware that I was writing it, but I was left alone to get on with it. I was grateful to anyone that spoke to me, however small his or her contribution. For me it was important to get to people that hadn’t talked about The Who before: the people they were at school with who played in their first trad-jazz and skiffle groups, for example. There was Chris Sherwin, the drummer in Pete’s first school group, with whom Townshend had a huge falling-out, which he talked about at length in his autobiography. Chris had never spoken about any of this before.

There was also Alan Pittaway, who played with Roger in a school group called The Sulgrave Rebels that won a skiffle competition in 1958. Once Alan had got over the shock of me tracking him down (I’m still not quite sure how I managed it), he was great because he hooked me up with two other ex-members of the group. They all gave me valuable background information, and a real flavour of what it was like growing up in West London in the late 50s and discovering rock’n’roll. Alan also gave me a copy of a photo of The Sulgrave Rebels which was published in the Acton Gazette & Post in 1958, and which we’ve reprinted in the book. It’s not been in print since 1958.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, you also had someone like Dr John Hemming, a world authority on South America’s indigenous people, who’d accompanied Kit Lambert on an expedition through the Amazon jungle in 1962 (where one of Lambert’s closest friends was killed by members of a previously unknown tribe). John was fascinating to talk to, especially as he sounded less disturbed by the dangers he faced in the Brazilian jungle than he did by seeing The Who at the Marquee three years later.

I’d also have to mention long-time friends of the band and Who experts, Richard Barnes and ‘Irish Jack’. Both told me things I’d never heard before, despite both men having been asked about The Who so many times and having written books of their own. I spent a convivial afternoon in the pubs and cafes of Surbiton with Barney, and he was great company. I also have to mention The Who’s former tour manager, John ‘Wiggy’ Wolff. Not everything Wiggy said was necessarily relevant to the book or would have made it past the lawyers, but almost everything he told me was extremely funny.

There have been quite a few biographies written about The Who and Pete Townshend over the years. Were you able to uncover any interesting stories that you haven’t heard before, and were you able to shed new light on any of the often-told tales?

In terms of new stories, I manage to unearth new eyewitness material about all the band members’ and Kit Lambert and Chris Stamp’s early lives, all of which I hope helped shed some light on how The Who developed as a band. In terms of the old stories, I still came up against conflicting accounts about Keith Moon’s 21st birthday and the infamous ‘Lincoln Continental in the swimming pool’ anecdote. Roger Daltrey maintains it did happen, and there’s an ex-DJ from Flint, Michigan, who now claims he saw it as well. Everybody else says it never happened.

I was pleased to be able to find out more about how Keith Moon joined The Who. Some say he auditioned at The Oldfield; some say he didn’t. But I managed to track down the session drummer, Dave Golding, who was playing with The Who that night at The Oldfield. Dave is in his seventies now and still plays the drums, and remembers being unimpressed by Keith’s playing, which he described to me as “very new, but not very good”.

Frustratingly, only a couple of days ago I had a phone call from someone that was at school with Keith Moon, and whom I’d contacted about 18 months ago. They’d only just found my email. Within two minutes of us talking he told me an extraordinary story about the schoolboy Keith stealing a coconut from a greengrocer’s on Ealing Road and attempting to smash it open on his head. There was, apparently “blood everywhere”. That’s the thing: there is always another story, another anecdote you haven’t heard before… But one of the things that did emerge from researching this book is that for all the hilarious Moon stories there were just as many that were sad or disturbing. I came away from this with the impression that it must have been incredibly difficult for the rest of The Who coping with Moon on a day-to-day basis, however funny and talented he was.

Do you have any interest in doing a follow up book that covers the 1970’s period and later?

I hadn’t considered this before. But I keep getting asked about this now. So maybe I should. I loved The Who’s music in the 70s, and another book would give me the opportunity to drone on – again – about Who’s Next, Quadrophenia, and one of my favourites and The Who's most underrated album, The Who By Numbers. You’ve got me thinking now. But that’s a story for another day.

To learn more about Mark Blake, please visit his website at markrblake.com.